As the election approaches, President Joe Biden is making regular calls to former President Barack Obama to catch up on the race or to talk about family. But Obama is making calls of his own to Jeffrey Zients, the White House chief of staff, and to top aides at the Biden campaign to strategize and relay advice.

This level of engagement illustrates Obama’s support for Biden, but also what one of his senior aides characterized as Obama’s grave concern that Biden could lose to former President Donald Trump. The aide, who was not authorized to speak publicly, said that Obama has “always” been worried about a Biden loss. And so, the aide added, he is prepared to “eke it out” alongside his former vice president in an election that could come down to slim margins in a handful of states.

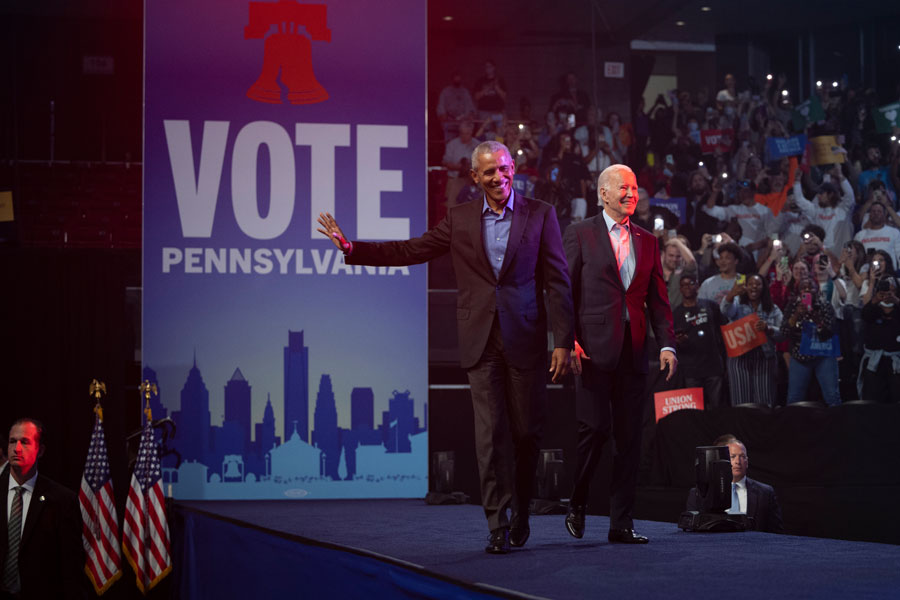

Perhaps for the first time, the two are on the same page about Biden’s future. In a sign of things to come, they are to appear together, with former President Bill Clinton, at a major fundraiser for the Biden campaign at Radio City Music Hall in New York on Thursday.

It was not always this way.

In 2015, as Biden was grieving the loss of his eldest son, Beau, and contemplating running for the presidency, it was Obama who gently suggested that it was not his time. In a memoir, “Promise Me, Dad,” Biden wrote that Obama told him that if he “could appoint anyone to be president for the next eight years,” it would have been Biden. The vice president wrote that “the mere possibility of a presidential campaign, which Beau wanted, gave us purpose and hope — a way to defy the fates.”

But after discussing the stakes with Obama, he took himself out of contention and stepped aside for Hillary Clinton, seen by the Obama White House as the far stronger candidate. The decision bred distrust and lasting resentment among some of Biden’s aides. Several of them work in the White House today, and they believe that Obama and his advisers sidelined Biden, whom they think could have changed the course of history and beaten Trump in 2016.

In 2019, when Biden entered the race against then-President Trump, Obama withheld his endorsement until after the Democratic primary, although he privately worked to clear a path for Biden. He also gave his blessing for the Biden campaign to use their interactions in the Obama White House in campaign materials, including footage of when Obama surprised his vice president with the Presidential Medal of Freedom shortly before leaving office.

In the 16 years since their first campaign together, the relationship has been defined by its odd-couple characteristics: The Harvard-trained professor and the guy from Scranton. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair who went on to serve a former junior member. The cool head and the Irish temper.

It took Obama time to warm to Biden, who was brought on as the Washington elder to help the exciting but inexperienced young president-to-be. Biden struggled with being second-in-command from the moment he joined the ticket.

The Obama brain trust, Biden and his allies felt, had no interest in taking strategic advice or additional requests from Biden, who had lost two prior presidential primary campaigns. On occasion, members of the Biden team — including Biden himself — groused about his second-class treatment by the Obama team, an elite and Ivy-educated machine.

One former campaign official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, recalled a moment of drawing the former vice president’s ire. After being asked to sign off on a statement on immigration policy, Biden snapped: “You mean the one I’ve had for 25 years? Or this guy’s?”

Over time the two jelled, with Biden leveraging his relationships on Capitol Hill to help steer a massive stimulus package through Congress in the Great Recession and to push the Affordable Care Act over the finish line. He famously congratulated Obama as the president signed the health bill into law, whispering “Mr. President, this is a big deal” with an inserted adjective not suited for national television.

The two were not aligned on everything. Biden was vehemently against Obama’s decision to send more American troops to Afghanistan in 2009, a disagreement that would become a focal point for Robert Hur, the special counsel who investigated the president’s handling of classified documents. A classified and handwritten document memo that Biden sent to Obama on Afghanistan had been found at Biden’s residence in Delaware by investigators.

In a lengthy interview in October with Hur, Biden hinted at their opposites-attract dynamic during a portion of the discussion that was meant to probe how often and in what manner he spoke with other senators about sensitive matters, including the Iran nuclear deal.

“The bad joke is, with President Obama, I would always say to him: Mr. President, all politics is personal,” Biden said at one point, explaining to Hur why he regularly invited senators to breakfast at the vice president’s residence.

Biden never explained the joke, but his recollection of the advice he gave to Obama highlighted a major difference between the two men, at least as far as Biden was concerned — he had nurtured relationships on Capitol Hill, something Obama had comparatively little interest in doing.

Aides to Biden say their relationship morphed from friendly to almost familial after Beau Biden died. When Obama delivered a eulogy for Beau in June 2015, the president looked down from the dais and told Biden that he and his family were “honorary members” of the Biden clan.

“And the Biden family rule applies: We’re always here for you, we always will be — my word as a Biden,” Obama said, a moment that has been described by people close to Biden as a major turning point for the president, who was stunned by Obama’s publicly affectionate remarks.

But during his interview with Hur, Biden explained another crucial disconnect: Obama’s differing view on Biden’s political future. Obama and his advisers had chosen Biden for his policy experience, but also because he had what the Obama team thought were limited career prospects beyond the vice presidency.

Biden recalled to Hur that, while he was pondering a presidential run in 2015, “there were still a lot of people at the time when I got out of the Senate that were encouraging me to run in this period, except the president,” he said, a reference to Obama. “I’m not — and not a mean thing to say. He just thought that she had a better shot of winning the presidency than I did,” a reference to Clinton.

People who were in the White House at the time argue that the timeline was not so simple.

“This notion that there was a red carpet available that, you know, Barack Obama blocked is just not based in reality,” David Plouffe, a former senior adviser to Obama, said in an interview. Plouffe said that Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont were already strong contenders for the Democratic nomination when Biden was considering a run.

“Joe Biden would have run for president for the third time, for the nomination, would not have succeeded, and would have never been president,” Plouffe said.

Still, White House officials and those working for Obama say that any lingering distrust at the staff level has dissipated, given what they see as the urgent need for Biden to beat Trump in November. Privately, Democrats close to Obama said that their concerns over Biden’s prospects have been assuaged somewhat by the president’s confrontational performance during his State of the Union address.

An email sent by Obama’s alumni group and obtained by The New York Times said as much. “We hope you are as fired up as we are after the State of the Union!” the group wrote in an email to supporters. “President Biden is ready.”

The New York Times