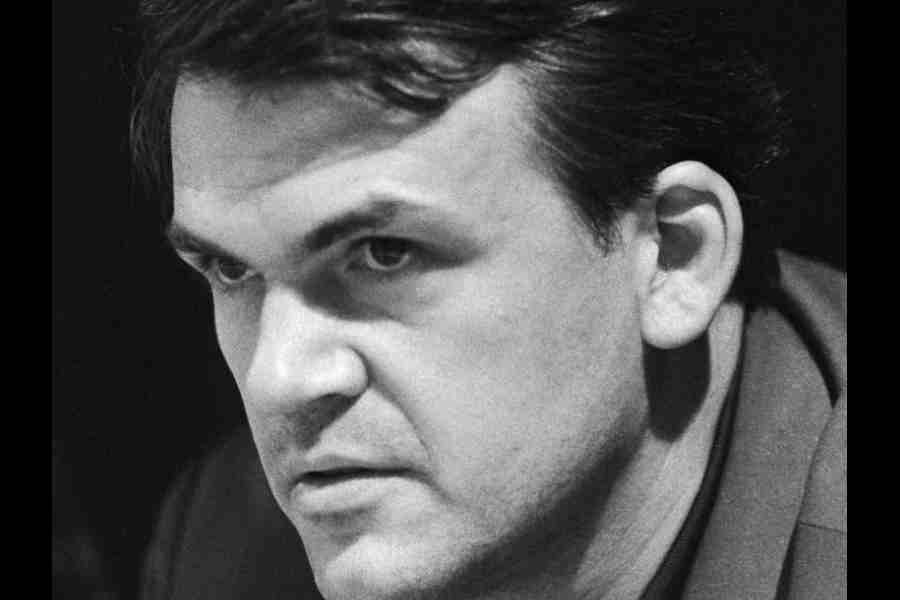

Milan Kundera, a Communist Party outcast who became a global literary star with mordant, sexually charged novels that captured the suffocating absurdity of life in the workers’ paradise of his native Czechoslovakia, died on Tuesday in Paris. He was 94.

A spokeswoman for Gallimard, Kundera’s publisher in France, said on Wednesday that Kundera had died “after a prolonged illness”.

Kundera’s run of popular books began with The Joke, which was published to acclaim in 1967, around the time of the Prague Spring, then banned with a vengeance after Soviet-led troops crushed that experiment in “Socialism with a human face” a few months later. He completed his final novel, The Festival of Insignificance (2015), when he was in his mid-80s and living comfortably in Paris.

The novel was his first new fiction since 2000, but its reception, tepid at best, was a far cry from the reaction to his most enduringly popular novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

An instant success when it was published in 1984, Unbearable Lightness was reprinted over the years in at least two dozen languages. The novel drew even wider attention when it was adapted into a 1988 film starring Daniel Day Lewis as one of its central characters, Tomas, a Czech surgeon who criticises the communist leadership and is consequently forced to wash windows for a living.

As punishments go, washing windows is a pretty good deal for Tomas: a relentless philanderer, he’s always open to meeting new women, including bored housewives. But the sex, as well as Tomas himself and the three other main characters — his wife, a seductive painter and the painter’s lover — are there for a larger purpose.

In putting the novel on its list of best books of 1984, The New York Times Book Review observed that “this writer’s real business is to find images for the disastrous history of his country in his lifetime”.

He could be especially pitiless in his use of female characters; so much so that the British feminist Joan Smith, in her 1989 book Misogynies, declared that “hostility is the common factor in all Kundera’s writing about women”.

Other critics reckoned that exposing men’s horrible behaviour was at least part of his intent. Still, even the stronger women in Kundera’s books tended to be objectified, and the less fortunate were sometimes victimised in disturbing detail.

Kundera’s fear that Czech culture could be erased by Stalinism — much as disgraced leaders were airbrushed out of official photos — was at the heart of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, which became available in English in 1979.

Writing in The Times Book Review in 1980, John Updike said the book “is brilliant and original, written with a purity and wit that invite us directly in; it is also strange, with a strangeness that locks us out”.

Kundera had a deep affinity with Central European thinkers and artists — Nietzsche, Kafka, the Viennese novelists Robert Musil and Hermann Broch, and the Czech composer Leos Janacek. Like Broch, Kundera said, he strove to discover “that which the novel alone can discover”, including what he called “the truth of uncertainty”.

His books were largely saved from the weight of this heritage by a playfulness that often meant using his own voice to comment on the work in progress.

Kundera told The Paris Review in 1983: “My lifetime ambition has been to unite the utmost seriousness of question with the utmost lightness of form. The combination of a frivolous form and a serious subject immediately unmasks the truth about our dramas (those that occur in our beds as well as those that we play out on the great stage of history) and their awful insignificance. We experience the unbearable lightness of being.”

He acknowledged that the names of his books could easily be swapped around. “Every one of my novels could be entitled The Unbearable Lightness of Being or The Joke or Laughable Loves,” he said. “They reflect the small number of themes that obsess me, define me and, unfortunately, restrict me. Beyond these themes, I have nothing else to say or to write.”

Kundera resettled in France in 1975 after giving up hope of political and creative freedom at home. His decision to emigrate underlined the choices available to the Czech intelligentsia at the time. Thousands left.

Among those who stayed and resisted was the playwright Vaclav Havel, who served several prison terms. He survived to help lead the successful Velvet Revolution in 1989 and then served as President.

With that great turnabout, Kundera’s books were legal in his homeland for the first time in 20 years. But there was scant demand for them or sympathy for him there: by one estimate, only 10,000 copies of The Unbearable Lightness of Being sold.

Many Czechs saw him as someone who had abandoned his compatriots and taken the easy way out. And they tended to believe a Czech magazine’s allegation in 2008 that he had been an informer in his student days and had betrayed a western spy. The agent, Miroslav Dvoracek, served 14 years in prison. Kundera denied turning him in.

Kundera was twice expelled from the party he had supported from age 18 when the communists seized power in 1948.

His first expulsion, for what he called a trivial remark, was imposed in 1950 and inspired the central plot of The Joke. He was nevertheless allowed to continue his studies; he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1952 and was then appointed to the faculty there as an instructor in world literature, counting among his students the film director Milos Forman.

Kundera was reinstated to the party in 1956 but kicked out again, in 1970, for advocating reform. This time it was forever, effectively erasing him as a person. He was driven from his job and, as he said, “no one had the right to offer me another”.

Over the next several years he picked up money as a jazz musician (he played the piano) and day labourer. And friends sometimes arranged for him to write things under their names or pseudonyms. Which was how he became an astrology columnist.

Yes. He had actually had experience casting horoscopes.

So when a magazine editor he identified as R. proposed a weekly astrology feature, he agreed, advising her to “tell the editorial board that the writer would be a brilliant nuclear physicist who did not want his name revealed for fear of being made fun of by his colleagues”.

He even cast a horoscope for R.’s editor-in-chief, a party hack who would have been disgraced if anyone had known of his superstitious beliefs. R. later reported that the boss “had begun to guard against the harshness the horoscope warned him about, was setting great store by the bit of kindness he was capable of, and in his often vacant gaze you could recognise the sadness of a man who realises that the stars merely promise him suffering”.

The two of them had a good laugh. Inevitably, though, the authorities would learn the true identity of the brilliant nuclear physicist-astrologer, and Kundera realised with certainty there was no way to protect friends who wanted to help him.

In his 1980 Times review, Updike commented that Kundera’s struggle “makes the life histories of most American writers look as stolid as the progress of a tomato plant, and it is small wonder that Kundera is able to merge personal and political significances with the ease of a Camus”.

Kundera was often nominated but not selected for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Enigmatic and private, and more than a little grumpy about the clatter and clutter of modern western society, Kundera was largely out of the public eye from 2000 until the announcement in 2014 that he had created yet another novel, The Festival of Insignificance, originally written in French.

As Kundera himself wrote in Insignificance, “We’ve known for a long time that it was no longer possible to overturn this world, nor reshape it, nor head off its dangerous headlong rush. There’s been only one possible resistance : to not take it seriously.”

He had struck a similar note in 1985, on accepting the Jerusalem Prize, one of several honours he received.

“There is a fine Jewish proverb,” he said in his acceptance speech: “Man thinks, God laughs.”

And then a fine Kunderian flourish.

“But why does God laugh? Because man thinks, and the truth escapes him. Because the more men think, the more one man’s thought diverges from another’s. And finally, because man is never what he thinks he is.”

New York Times News Service