British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s estranged wife, Marina Wheeler, has broken her dignified silence by revealing she has been battling cervical cancer.

Marina has also confirmed that her much anticipated book on the Indian side of her family — The Lost Homestead — will be published by Hodder & Stoughton in spring 2020.

Her full-page article in The Sunday Times, London, is couched in emotional terms whose message may not be lost on the British public at large: “They told me it was cancer. I said: I don’t have time for that right now.”

Her account is summed up by the paper as follows: “Diagnosed with cervical cancer, Marina Wheeler underwent two operations in a week. Doctors saved her life, but her family, friends and Macmillan (a cancer hospital) nurses pulled her through.”

Marina, 55, a barrister who is a Queen’s Counsel, and Boris, 55, now Prime Minister, were married in 1993, and have four children, the youngest of whom, Theodore Apollo, 20, was born in 1999.

In describing the events of this summer, Marina discloses that she received treatment for her cancer where “twenty years to the day, I had given birth, here in

UCH (University College Hospital), to my youngest child”.

In June, Marina attended two days of the Khushwant Singh Literary Festival held at King’s College London where no one had any idea she was about to undergo critical surgery.

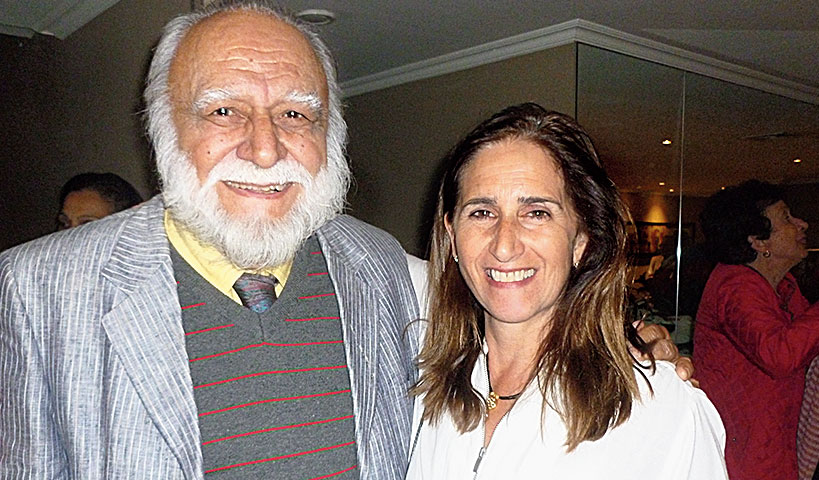

The festival is now an annual affair, organised by Khushwant’s journalist son, Rahul Singh, to whom Marina is related by marriage. Marina and her elder sister, Shirin, are the daughters of Dip Singh, who in 1961 married the distinguished BBC journalist, Sir Charles Wheeler, who was once based in Delhi.

Dip had previously been married to Khushwant’s youngest brother, Daljit Singh, a national junior tennis champion.

In 2012, the Indian Journalist’s Association in London gave a lifetime achievement award to Sir Charles, which was handed over by the then Indian high commissioner in London, Jamini Bhagwati, to Marina and Shirin.

Marina has been to India since to conduct research into her family background.

She told The Sunday Times of the importance of regular cervical screening, or smear tests, after a routine check in January revealed the problem that led to procedures in June and July.

“I know the take-up of smear tests is way down,” she said. “I know they can save your life. If people are willing to listen — as they seem to be — why not say so? Why be afraid? I would urge other women to make the time and do the tests.”

She said: “Some weeks earlier, in May, Mr K of the Whittington Hospital had delivered the diagnosis. His explanation was clear and careful. He was very sorry. I would be referred immediately to the gynaecological oncology team at University College Hospital (UCH), a world-class centre for this kind of thing — this kind of thing being cervical cancer.”

Speaking of her reaction, she said: “I left thinking, ‘That’s absurd. I have no time for this. Quite apart from everything else, I have a book to write.…’”

Marina added that she considers herself to be free of cancer, saying the experience made her appreciate “the incalculable value of holding close those who you love and trust”.

Marina ends her account with the words: “I am now in the garden at (close friend) Lucy’s house in Cornwall. It is lush and filled with flowers. I feel the sun warming my back. I can hear birds and the rhythmic roar of the sea. I am also making progress with my manuscript, while pondering other things. One is womanhood. It is true, I have lost some key anatomical bits. They served me well but had no further use. And that is fine. In this age, in the place we live, we are defined much less by our desire or ability to reproduce. Why should we, when there is so much more?”