In their winning bid to host the 2028 Summer Olympics, Los Angeles leaders pledged that the city’s version of the Games would be the greenest ever — a goal they planned to achieve in large part by making access to the event “car-free.”

It was a bold statement because, well, it’s Los Angeles. Could America’s capital of car culture, where traffic shapes daily life more than the weather, really pull that off?

As the Paris Olympics come to a close this weekend, the clock is ticking. Los Angeles must complete much-needed upgrades to the region’s transit system to handle an influx of athletes and visitors without bringing car traffic to a standstill. That includes extending rail lines, adding a legion of buses and clearing countless traffic lanes to allow hundreds of thousands of people to navigate a metropolis that sprawls across 4,000 square miles.

“I’m optimistic,” said Eli Lipmen, executive director of Move L.A., an organization that advocates for the expansion of public transit in the region. “There’s nothing better than a deadline.”

At the closing ceremony Sunday, Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass will receive the official Olympic flag, which she will bring back to Los Angeles to mark the official countdown to the 2028 Games. And on Saturday at a news conference in Paris, she reiterated that those Games would be “no-car.”

But in some ways, the dream of a car-free — or, as organizers have been putting it more recently, “transit-first” — Olympics in Los Angeles may feel even more out of reach than it did seven years ago, when it was named the host city for the third time.

Ridership on public transit, which includes 109 miles of rail lines and nearly 120 bus routes, plunged during the coronavirus pandemic, as it did in cities nationwide, and has yet to fully rebound. Usage of Los Angeles’ Metro system is at about 85% of its 2019 levels, according to the transit agency. And it’s not uncommon for public transit trips in Los Angeles to take twice as long as driving because of infrequent service and stops that are far from some people’s homes.

The rise in the region’s homeless population has turned some Metro trains and buses into de facto shelters, making many riders feel unsafe, and high-profile incidents of violence on the system have amplified those concerns.

Overall road traffic has increased. Last year, the average driver in Los Angeles lost 89 hours to congestion, one of the highest numbers in the nation, as driving trips in the middle of the day have surged with fewer people making daily commutes to work, according to transportation analytics company INRIX.

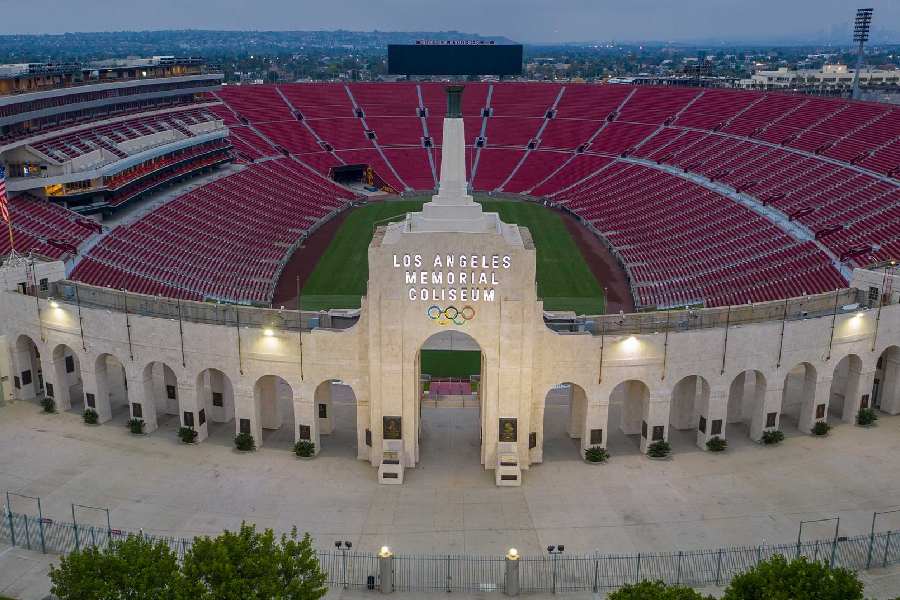

Adding in gameday traffic at virtually every major venue in the region, from the storied Rose Bowl Stadium in Pasadena to the Long Beach Convention Center, could seem apocalyptic for drivers.

But Los Angeles leaders say all of that makes the Olympic Games a unique chance to finally free Angelenos from their cars and the hours of gridlock they endure by showing them what’s possible — if officials can get enough done in four years.

“It’s an incredibly good opportunity to showcase the multibillion-dollar investment we’ve had in infrastructure,” said Stephanie Wiggins, CEO of Los Angeles’ Metro system, which is overseen by elected officials representing Los Angeles County, as well as some of the 88 cities within it.

Metro’s bold plan to improve the region’s transit system in time for the Olympics features a combination of long-planned upgrades and quicker fixes. As part of the plan, which is called “28 by ’28” and consists of dozens of projects, a new rail line through South Los Angeles opened in 2022. And last year, Metro unveiled the longest light-rail line in the country, which offers a direct route from East Los Angeles to Santa Monica.

But the to-do list is long, and only five of the projects are complete. Construction on a dedicated rapid bus lane along Vermont Avenue, a major north-south corridor where riders make 45,000 trips per day, has not even begun. And pressure is building to finish extending the subway’s Purple Line from downtown Los Angeles to the University of California, Los Angeles, campus, where the athletes village will be, which could turn a two-hour drive into a 30-minute train ride.

”I think the biggest challenge is that not as much of the transit system is likely to be complete by 2028 as might have been hoped,” said Joshua Schank, a senior fellow at the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies and a former chief innovation officer for Metro.

Some residents share those doubts. Sebastiaan Gregoir, 45, a film and TV editor who lives downtown, said that the city was courageous in the way it was investing in public transit. But on the question of whether the Metro system would be ready to handle the Olympics, he’s far from convinced.

“My answer is probably no,” he said. “In public transport, four years is nothing. It’s tomorrow basically.”

Paris, too, had vowed to make its Games fully accessible by transit — and succeeded. The city is more walkable and has better transportation infrastructure. (It also had signage everywhere and an army of volunteers pointing people where to go.)

But there are measures Los Angeles can take beyond transit upgrades to ease congestion during the event. The city can alter truck delivery times and encourage remote work, said Casey Wasserman, chair of LA28, which is organizing the 2028 Olympics. He and others in the group have been in Paris observing day-to-day operations of this year’s Games. Wasserman added that communication campaigns and partnerships with city and transit groups were also essential.

During the 2028 Olympics, Metro is planning to borrow more than 2,700 buses to help transport athletes and visitors. California’s transit agency will designate freeway lanes for buses only.

That was also the plan for the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, before rail lines even existed in the city. Despite worries in the lead-up to the Games, the bus system, in addition to staggered work schedules that were adopted by businesses, added up to extraordinarily light traffic, or “automotive nirvana,” as the Los Angeles Times reported at the time.

Bass has said that this time around, the city has more public transportation options, as well as technology that can facilitate remote work to keep the roads as empty as possible.

She has also noted that Los Angeles will get a couple of dress rehearsals before the Games. The region is slated to host some matches for the World Cup in 2026 and the Super Bowl in 2027.

Some Angelenos said that although they were skeptical about whether they would see gleaming new stations or better lit subway cars in a transformed Metro system in the next four years, they would be open to using transit if it was convenient.

Nick Andert, 36, a documentary producer who lives in West Hollywood, a walkable enclave surrounded by the city of Los Angeles, said he would welcome a way to get to the Games without a car.

“I definitely hate the idea of trying to drive and park,” he said.

(New York Times news service)