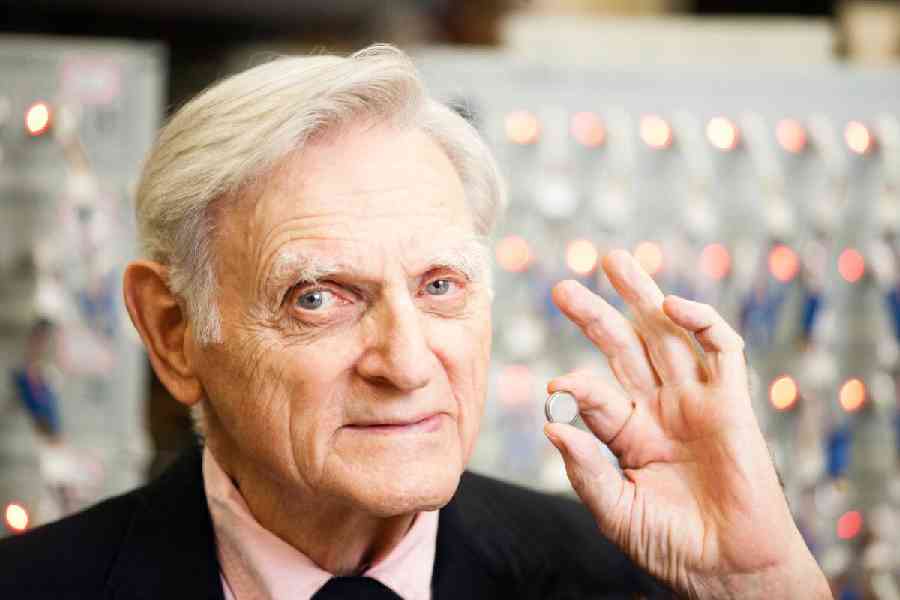

John B. Goodenough, the scientist who shared the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his crucial role in developing the revolutionary lithium-ion battery, the rechargeable power pack that is ubiquitous in today’s wireless electronic devices and electric and hybrid vehicles, died on Sunday at an assisted living facility in Austin, Texas. He was 100.

The University of Texas at Austin, where Dr Goodenough was a professor of engineering, announced his death.

Until the announcement of his selection as a Nobel laureate, Dr Goodenough was relatively unknown beyond scientific and academic circles and the commercial titans who exploited his work. He achieved his laboratory breakthrough in 1980 at the University of Oxford, where he created a battery that has populated the planet with smartphones, laptop and tablet computers, lifesaving medical devices like cardiac defibrillators, and clean, quiet plug-in vehicles, including many Teslas, that can be driven on long trips, lessen the impact of climate change and might someday replace fuel-powered cars.

Like most modern technological advances, the powerful, lightweight, rechargeable lithium-ion battery is a product of incremental insights by scientists, lab technicians and commercial interests over decades. But for those familiar with the battery’s story, Dr Goodenough’s contribution is regarded as the crucial link in its development, a linchpin of chemistry, physics and engineering on a molecular scale.

In 2019, when he was 97 and still active in research at the University of Texas, Dr Goodenough became the oldest Nobel Prize winner in history when the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that he would share the $900,000 award with two others who made major contributions to the battery’s development: M. Stanley Whittingham, a professor at Binghamton University, State University of New York, and Akira Yoshino, an honorary fellow for the Asahi Kasei Corporation in Tokyo and a professor at Meijo University in Nagoya, Japan.

Dr Goodenough received no royalties for his work on the battery, only his salary for six decades as a scientist and professor at MIT, Oxford and the University of Texas. Caring little for money, he signed away most of his rights. He shared patents with colleagues and donated stipends that came with his awards to research.

A congenial presence since 1986 on the Austin campus, where he amazed colleagues by remaining active and inventive well into his 90s, he had been working in recent years on a superbattery that he said might someday store and transport wind, solar and nuclear energy, transforming the national electric grid and perhaps revolutionising the place of electric cars in middle-class life.

A devoted Episcopalian, Dr Goodenough kept a tapestry of the Last Supper on the wall of his laboratory. Its depiction of the Apostles in fervent conversation, like scientists disputing a theory, reminded him, he said, of a divine power that had opened doors for him in a life that had begun with little promise.

He was, he said in a memoir, Witness to Grace (2008), the unwanted child of an agnostic Yale University professor of religion and a mother with whom he never bonded. Friendless except for three siblings, a dog and a maid, he grew up lonely and dyslexic in a distant household.

New York Times News Service