Lee A. Iacocca, the visionary automaker who ran the Ford Motor Co. and then the Chrysler Corp. and came to personify Detroit as the dream factory of America’s postwar love affair with the automobile, died on Tuesday at his home in Bel Air, California. He was 94.

He had complications from Parkinson’s disease, a family spokeswoman said.

In an industry that had produced legends, from giants like Henry Ford and Walter Chrysler to the birth of the assembly line and freedoms of the road that led to suburbia and the middle class, Iacocca, the son of an immigrant hot-dog vendor, made history as the only executive in modern times to preside over the operations of two of the Big Three automakers.

Detractors branded him a Machiavellian huckster who clawed his way to pinnacles of power in 32 years at Ford, building flashy cars like the Mustang, making the covers of Time and Newsweek and becoming the company president at 46, only to be spectacularly fired in 1978 by the founder’s grandson, Henry Ford II. But admirers called him a bold, imaginative leader who landed on his feet after his dismissal and, in a 14-year second act that secured his worldwide reputation, took over the floundering Chrysler Corp. and restored it to health in what experts called one of the most brilliant turnarounds in business history.

He accomplished it with a controversial $1.5 billion federal loan guarantee, won by convincing the government that Chrysler was vital to the national economy and should not be allowed to fail, and with concessions from unions, new lineups of cars, and a new national spokesman — himself — featured in a decade-long television advertising campaign.

A heroic figure to many Americans, he became chairman of a project to restore the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, and was in demand for speeches and public appearances that took on the colour of a campaign. He conferred with President Ronald Reagan, members of Congress, governors and business leaders. He was mobbed by admirers and pursued by the press. Polls confirmed that a run for the White House was realistic, and his denials of political ambition only fuelled public interest in a possible candidacy.

But by the late 1980s, storm clouds that Iacocca and other auto executives had long ignored were gathering. The stock market had plunged in 1987, and Japan, long since recovered from the disasters of World War II, had become a world-class economic power, whose fuel-efficient cars were flooding the United States. Americans wanted reliable, well-built cars with innovations like air bags, and Honda and Toyota were supplying them.

Trying to reverse the decline, Iacocca established partnerships with Mitsubishi, Maserati and Fiat, but they were no panacea. Finally surrendering to pressures to step down, he hired Robert J. Eaton, the head of GM’s European operations, as his designated successor, and retired as Chrysler’s chairman and chief executive in 1992.

“He’s like Babe Ruth,” Bennett E. Bidwell, a retired Chrysler executive, said of Iacocca. “He hit home runs and he struck out a lot. But he always filled the ballpark.”

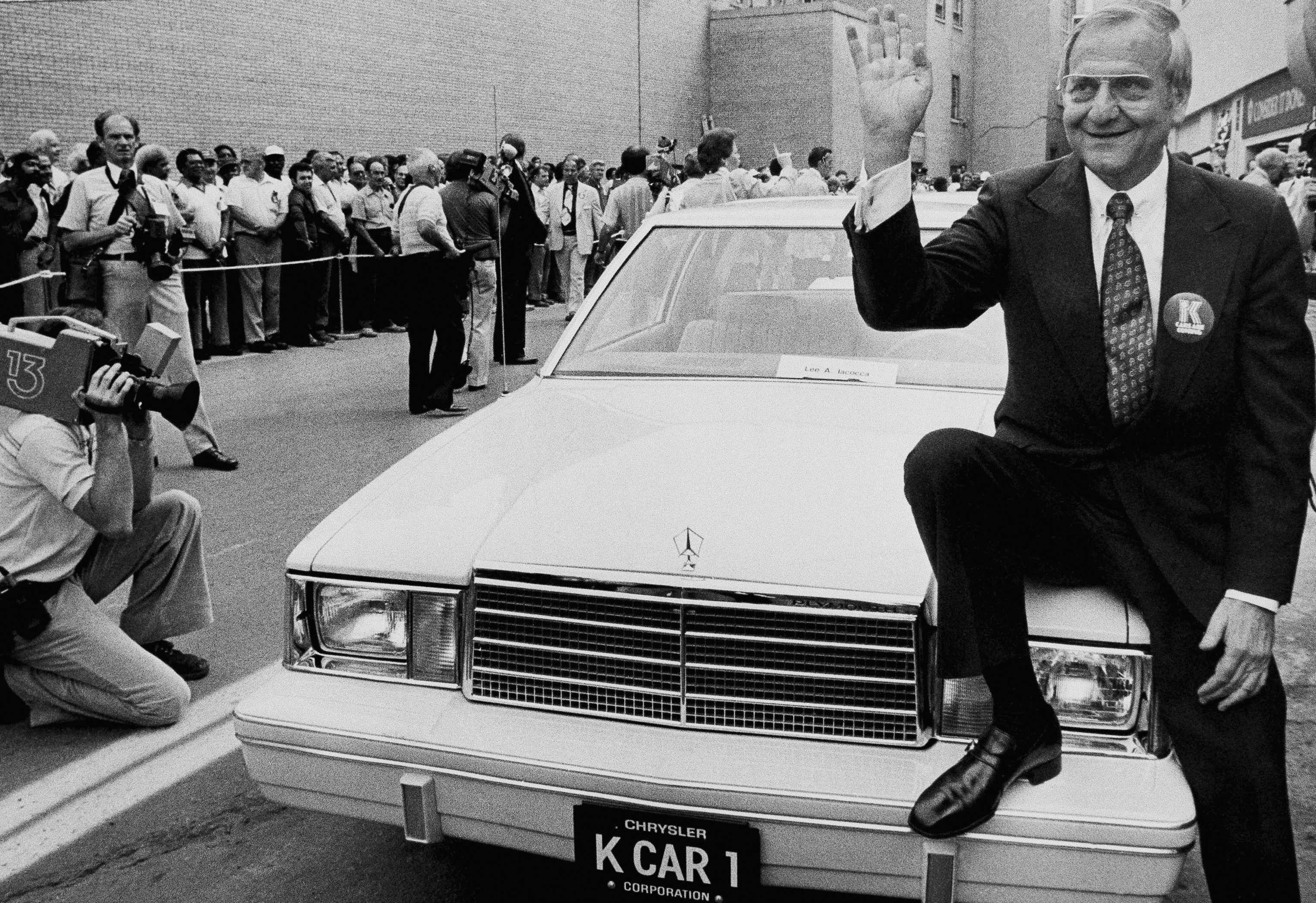

In this August 6, 1980, file photo, Chrysler Corp. chairman Lee Iacocca sits on the hood of K Car Number One, a Plymouth Reliant, in Detroit. (AP)

He was born Lido Anthony Iacocca on Oct. 15, 1924, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, one of two children of Nicola and Antoinette Perrotto Iacocca, immigrants from San Marco, Italy, who named him after the Venice beach resort. He and his sister, Delma, grew up in Allentown.

Their father had little education. He started as a hot-dog vendor in Allentown, borrowed money and went into real estate and other ventures. But he later acquired several movie theatres and opened one of the country’s first car-rental companies with a small fleet of Fords, and Lido grew up talking cars with his father.

At Lehigh University in nearby Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, he graduated after three years with a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering.

He also impressed a Ford recruiter and was hired for an executive training program. He decided to change his foreign-sounding first name to Lee, a serious concession for a young man proud of his ethnicity.

In 1956, Iacocca married Mary McCleary, a Ford receptionist in Chester, Pennsylvania. They had two children, Kathryn Iacocca Hentz and Lia Iacocca Assad, who survive him, as do a sister, Delma Kelechava, and eight grandchildren. His first wife died in 1983 from complications of diabetes. In 1986 he married Peggy Johnson, a former flight attendant. The marriage was annulled in 1987. In 1991 he married Darrien Earle, whom he divorced in 1994.

He learned the subtle, sometimes brutal, strategies of the executive scramble. But he out-manoeuvred rivals for the executive suite and was named president of Ford in 1970, the No. 2 post, reporting only to the chairman, Henry Ford II.

Ford fired Iacocca in July 1978, saying he just did not like him. He never gave more detailed reasons. Several months later, Iacocca joined Chrysler.

After retiring, Iacocca moved to Bel Air, California, where he invested in electric bicycles, olive oil and other ventures and promoted diabetes research.

In addition to his autobiography, Iacocca wrote “Talking Straight” (1988) with N.R. Kleinfield, then a reporter for The New York Times, and “Where Have All the Leaders Gone?” (2007) with Catherine Whitney.