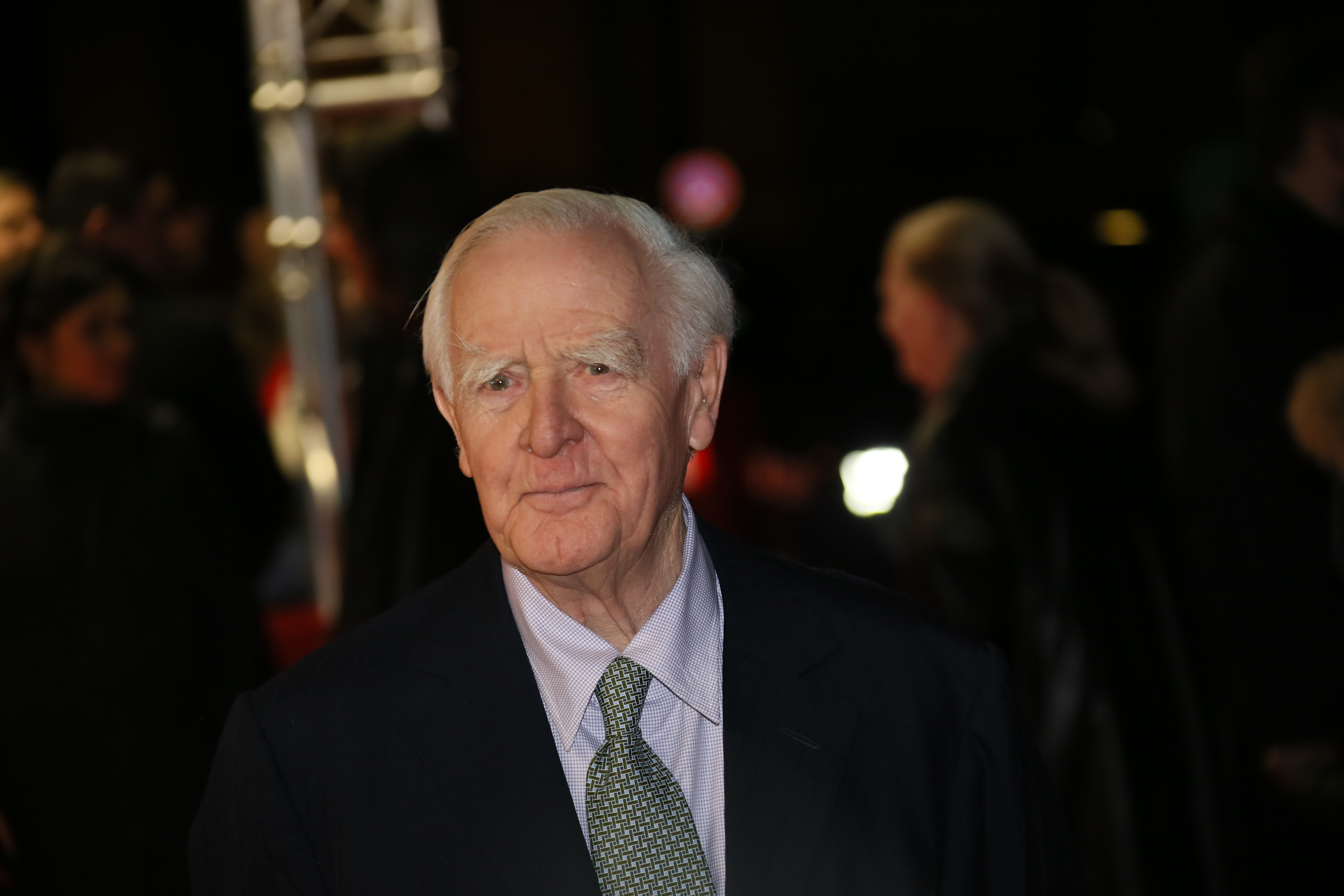

When John le Carré was running agents for the British secret intelligence service MI6 in the early 1960s, there were certain qualities he looked for in a candidate. Gregariousness, cocktail party charm, the ability to hold one’s drink — all of that mattered, of course. But above all, what le Carré wanted was “a sense of larceny”, as he explains during an interview at his north London home. “Somebody who enjoys the adventure and is not scrupulous about small stuff.”

In his new novel, Agent Running In the Field — set in modern-day Britain — the main character, Nat, is called out by his daughter about his lack of ethics. “For the sake of a country that you have serious reservations about, even very serious, you persuade other nationals to betray their own countries,” she tells him. Nat counters with an argument which le Carré admits is similar to his own: “I don’t think I persuaded anybody to do anything they didn’t want to do,” le Carré says. “I think I enabled them to do it and provided the protection.”

This morally murky world of spying is where le Carré continues to make his literary mark. Agent Running in the Field, which Viking will publish on October 22, is his 25th novel. It comes only two years after his last, A Legacy of Spies, and shows that, approaching his 88th birthday, the author isn’t exactly slowing down.

“I have no real leisure activity,” le Carré says. “I am dismayed when I’m not writing, completely content when I am. I also find, thus far, that I’m unaware of any relaxation of my talent. I also am stimulated and appalled by the path my country has taken.”

Agent takes aim at Brexit and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, whose previous stint as foreign secretary is witheringly invoked. In the late 1950s le Carré taught foreign languages at Eton, Britain’s most elite all-boys’ boarding school. It gave him insight into a culture that has provided Britain with a production line of Old Etonian politicians, including Johnson.

“I’ve taught a dozen Johnsons,” le Carré says. “Eton does something extraordinary. It doesn’t teach you to govern. It teaches you to win. That’s what it’s about.”

Like Legacy before it, Agent taps into the disillusionment of ageing spies who turn their backs on the British establishment after years of loyal service because the cause they once espoused has gone.

“There are a whole lot of things about the secret world that are shocking and unpleasant, but in the years when I worked for it there was at least a motive,” le Carré says. This motive, of course, was to win the Cold War, which at its most basic level was a war governed by opposing ideologies.

Le Carré got his first taste of “the secret world” in 1949 at 17 after running away from his English boarding school, which he detested. He ended up in Bern, Switzerland, where he came to the attention of a Swiss MI6 station while he was studying foreign languages at a local university.

They soon tapped him for trivial jobs.

“I didn’t quite know who I was working for then, but I was filled with a Boy Scout feeling of loyalty at that age because my wartime experience had produced only heroes — male heroes, school masters who came back in uniform,” he says.

The contrast with le Carré’s con man father, Ronnie, whose wayward life inspired his mesmerising novel A Perfect Spy (1986), could not have been more pronounced. “I didn’t have any kind of orthodox upbringing,” says le Carré, who chose a French-sounding pen name to complement his birth name, David Cornwell. “I had to write my own ethics and morality, if you like.”

After college, le Carré completed two years of compulsory military service, which included running British agents into Soviet-occupied Austria.

Then he returned to England and began working for MI5, the domestic branch of the British Security Service. After studying at Oxford and teaching at Eton he was recruited by MI6, the service’s foreign branch, in 1960.

He left MI6 in 1964 to focus full-time on writing when his career exploded with the publication of his third novel, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold.

That novel was inspired by the time le Carré spent running agents between West and East Germany, which left him with a deep love of German culture and language. Today he finds he can only sit down to a book for a couple of hours straight if it’s in German. “I assume I’m dyslexic because I’m a terribly slow reader and with time I get slower and slower,” he says. “But I find German probably just starts the old clock going of my student years. So I can sit down and really settle to a Thomas Mann short story.”

Le Carré believes an opportunity was missed when the Berlin Wall came down. “There was no great leader who came forward and said, ‘Listen, this is the moment to redesign the world,’” he says.