British poet and writer Rudyard Kipling, an ardent supporter of his country’s entry into World War I, did everything he could to make sure his only son would join the fight.

Yet just a few weeks after John Kipling touched French soil on the day of his 18th birthday, he was reported missing during the devastating Battle of Loos on September 27, 1915.

His father and mother Carrie would spend the next several years desperately searching for him, hoping against all odds that he might have survived.

It was not until 1919 that Kipling publicly acknowledged his son was probably dead, one of the 1.1 million soldiers lost by the British Empire in the war.

The author of The Jungle Book, the first Briton to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, fiercely defended the war as a patriotic duty for all able-bodied men. He threw himself into the government’s propaganda efforts, and is believed to have popularised the slur “Hun” in reference to the German foe.

But John, who hoped to enlist in the Royal Navy, was rejected because of poor eyesight. “As his wife said: How could their son not go to war when all the other sons were?” said David A. Richards, who has published a bibliography of the author’s work and letters.

It was only thanks to his father’s connections as one of the country’s most popular writers that he finally got a commission in the Irish Guards, and shipped out to France in August 1915.

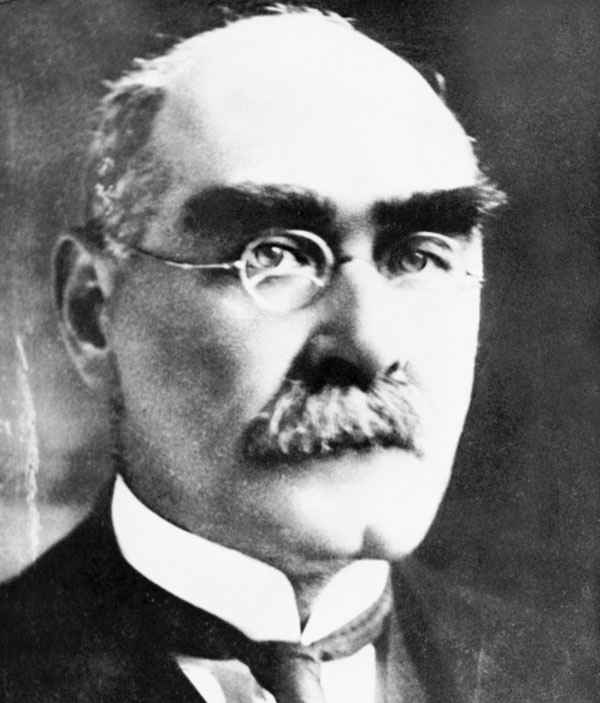

Rudyard Kipling (Agencies)

Shortly afterwards came the Battle of Loos, which proved a disaster for Britain as waves of soldiers were cut down by German machine guns or choked on their own poison gas being blown back into their lines. An estimated 15,000 British soldiers were killed and 35,000 wounded in a matter of days.

It was John’s first combat experience, and he disappeared after “going over the top”, leaving the trenches to attack enemy lines.

“A telegram from the War Office to say John is ‘missing’,” reads an entry in Carrie’s diary from October 2, 1915.

From that day on, Kipling moved heaven and earth to find out what happened to his son. Hoping he might just be wounded or captured, Kipling spent months tracking down members of his regiment to try to learn where John was last seen.

He even managed to have leaflets dropped over enemy lines asking for news of his son. “He begged the War Office not to declare the boy dead, only missing, to spare his wife’s feelings,” Richards said.

Kipling would return repeatedly to the French battlefields hoping to learn his son’s fate until his death in 1936. But it was only in 1992 that John’s grave was finally identified thanks to archival research, at St Mary’s cemetery in Haisnes, near the battlefield where he disappeared.

His name has since replaced the inscription “Known unto God”, a phrase suggested by Kipling himself to the Imperial War Graves Commission, which he joined after his son’s disappearance.

“After the war, Kipling’s writing took on a generally more serious tone, including several stories about soldiers suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder,” according to Mike Kipling, one of the author’s descendants and chairman of the Kipling Society.

In 1916 he would write the haunting lines of My Boy Jack: “Have you news of my boy... What comfort can I find?”

Whether a sign of his own regrets or criticism of those responsible for the carnage, Kipling would later write in his Epitaphs of the War: “If any question why we died, Tell them, because our fathers lied.”