On a January evening in 2019, Joe Biden placed a call to the mayor of Los Angeles, Eric Garcetti, a personal friend and political ally who had just announced he would not pursue the Democratic nomination for President.

During their conversation, Garcetti recalled, Biden did not exactly say he had decided to mount his own campaign. The former vice-president confided that if he did run, he expected President Donald Trump to “come after my family” in an “ugly” election.

But Biden also said he felt pulled by a sense of moral duty.

“He said, back then, ‘I really am concerned about the soul of this country,’” Garcetti said.

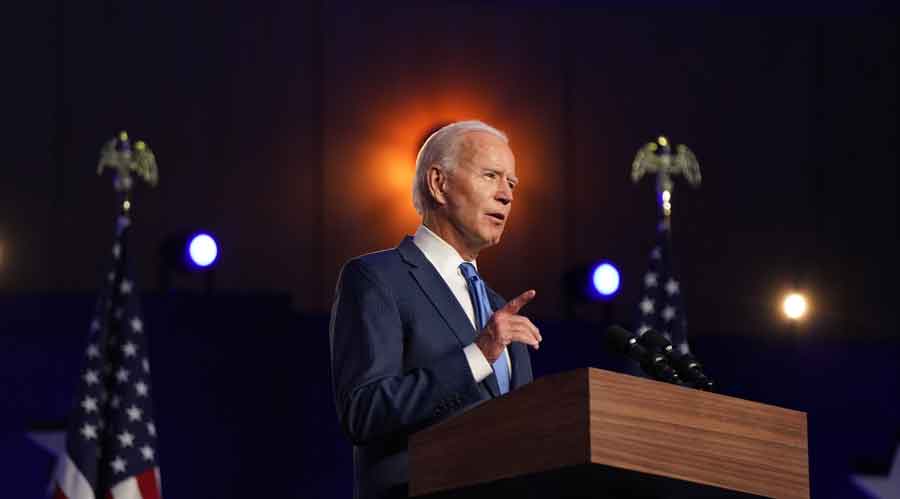

Twenty-one months and a week later, Biden stands triumphant in a campaign he waged on just those terms: as a patriotic crusade to reclaim the American government from a President he considered a poisonous figure. The language he used in that call with Garcetti became the watchwords of a candidacy designed to marshal a broad coalition of voters against Trump and his reactionary politics.

It was not the most inspirational campaign in recent times, nor the most daring, nor the most agile. His candidacy did not stir an Obama-like youth movement or a Trump-like cult of personality: there were no prominent reports of Biden supporters branding themselves with “Joe” tattoos and lionising him in florid murals — or even holding boat parades in his honour.

Biden campaigned as a sober and conventional presence, rather than as an uplifting herald of change. For much of the general election, his candidacy was not an exercise in vigorous creativity, but rather a case study in discipline and restraint.

In the end, voters did what Biden asked of them and not much more: they repudiated Trump, while offering few other rewards to Biden’s party.

Throughout his campaign, Biden faced persistent doubts about his political acuity and the relevance, in the year 2020, of a set of union-hall-meets-cloakroom political instincts developed mainly in the previous century.

But if Biden made numerous errors along the way, none of them mattered more in this election than the essential rightness of how he judged the character of his party, his country and his opponent.

During the primaries, Biden rebuffed pressure to move to the Left, believing his party would embrace his pragmatism as its best chance to beat Trump. In the general election, Biden made Trump’s erratic conduct and mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic his overwhelming themes, shunning countless other issues as needless distractions.

While some Democrats urged him to compete in a wider array of battlegrounds, Biden put the Great Lakes states at the centre of his electoral map, trusting that with an appeal to the political middle he could rebuild the so-called Blue Wall and block Trump’s path to a second term.

Crucial factor

Perhaps most important, Biden believed that no issue would figure larger in voters’ minds than Trump’s presence in the Oval Office. And if he could make the election an up-or-down vote on an out-of-control President, he believed he could win.

On that score, he was right. As voters sized up Biden as a potential President, his familiar flaws and foibles — the antiquated vocabulary and penchant for embellishment, his nostalgic yarns about segregationist senators and a defensiveness that led him, in one case, to challenge a voter to a push-up contest — paled against the conduct of an incumbent sowing racial division, threatening to deploy troops in American cities and floating the idea of injecting disinfectant as a coronavirus treatment.

Anita Dunn, one of Biden’s closest advisers, said the campaign had been propelled all along by the candidate himself, and his unwavering theme and strategy.

“It was his campaign,” Dunn said. “It was less consultant-driven than any presidential campaign in modern history.”

Still, at the outset, Biden’s political theory of the case struck even some of his loyal allies as misguided in an era of intense ideological polarisation.

Senator Bob Casey of Pennsylvania recalled a meeting he had with the former vice-president in March of 2019, shortly before Biden entered the race. As Biden sketched out his approach, Casey, a Democrat, was not fully convinced.

“He was walking through what became his broader-based theme, about the soul of the country,” Casey said. “I was worried at the time that it wasn’t hard-hitting enough.”

But Biden, he said, “was prescient in his ability, even in the primaries when almost nobody else was doing it, to say, ‘We have to bring the country back together’.”

Casey was not the only Democrat sceptical of Biden’s underlying theme. While many voters found Trump distasteful, or worse, it is difficult to unseat an incumbent President and Trump had the benefit of a nation in relative peace and steady prosperity. Biden’s primary opponents, who argued that a message of normality and steady experience might not be enough to win, seemed to have a point.

Pandemic strikes

Then, just as Biden was seizing a clear upper hand in the Democratic nomination fight, the coronavirus pandemic struck. In a matter of days, public campaigning froze and a mood of fear and gloom set in across the country.

Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, a close ally of Biden, said it was not immediately obvious that the Trump administration would effectively forfeit the issue of public health to Biden.

But as Trump dismissed the threat of the pandemic, and railed against governors like Whitmer for locking down their states, Biden moved to assert himself as an alternative leader. He began to sketch his own approach to addressing the disease, and to show voters how he might operate in Trump’s place.

From the confines of his lakeside home in Wilmington, Delaware, he received frequent briefings about the pandemic and the economic damage it was inflicting, drafted policy plans and reached out to state and city leaders to gather information.

“He was calling to say, ‘How are things going in Michigan? What do you need?’” Whitmer said.

What Biden was not doing, to the dismay of some in his party, was travelling the country and campaigning in person. For months, he scarcely left the immediate vicinity of his home: at 77, he was in an age group especially vulnerable to the virus, and his advisers felt he could undermine his own public-health recommendations if he was seen as racing back onto the campaign trail. And more than a few political donors and Democratic advocacy groups second-guessed the Biden campaign’s decision to forego a robust get-out-the-vote operation in the field because of safety concerns.

Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, said Biden had seemed at first to pay a price for his caution. Allies of the Biden campaign had tried to nudge the former vice-president into public view, he said, paraphrasing the plea: “People need to see you.”

But in his own conversations with the Biden team, Morial said, they were emphatic that Biden felt he could not “say one thing and do another” where public health was concerned — a judgement that Morial came to share.

Biden’s first major trip outside Delaware was not for a traditional campaign trip but to confront another crisis: the national reckoning over police brutality after the killing of George Floyd. Flying to Houston to visit the Floyd family, Biden sat for two hours as he listened to the grieving family and told them that while he had never experienced loss quite like theirs, he knew what it meant to lose a child and felt their pain, according to the Rev. Al Sharpton, who was present.

When racial-justice protests turned disorderly in Atlanta, Biden reached out to the city’s mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, to offer support and private counsel.

The former vice-president, Bottoms said, was both encouraging and contemplative, telling her how the spiralling demonstrations evoked, for him, the riots in Wilmington in the late 1960s, which led to an extended occupation of the city by the National Guard.

It was a study in the personal empathy, and the hunger to connect with other people, that defined Biden as a candidate from the start. Throughout the race he invoked his own family’s history of tragedy, and never more so than in confronting the immense pain and loss of the coronavirus pandemic.

“He is able to personalise these big issues,” Bottoms said. “He really does have a sensitivity and a personal lens for many of these challenges that we’re facing.”

Biden also recognised that his opponent lacked that impulse.

Perilous moment

The most perilous moment of the race for Biden may have come in late August, when a season of racial-justice protests had given way to spasms of vandalism and arson in a handful of politically important states.

At the Republican nominating convention, the President and his allies pounded Biden for a week with false or overstated attacks, linking him both to criminals and to Left-wing activists who had taken up “defund the police” as a slogan.

The onslaught posed a distinctive challenge to Biden, threatening to weaken his coalition of racial minorities, young liberals and moderate whites. Trump began a scare campaign aimed in part at white women, telling them he would “save your suburbs” from what he portrayed as looting mobs that Biden would not control.

Like other liberals of his generation, Biden saw danger in the Kenosha riots. Recalling the riots in American cities after the assassinations of the 1960s, he telephoned an adviser, saying he wanted to denounce the violence and asking a question: What had Robert F. Kennedy said to cool tempers in the aftermath of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder?

Biden flew to Pittsburgh the following Monday to head off Trump’s attacks: in a 24-minute speech, he reaffirmed his support for police reform while sternly denouncing civil unrest. “Looting,” he said, “is not protesting.”

“We need justice in America. We need safety in America,” Biden said.

The Biden campaign turned a clip from the speech into a television ad and ran it at saturation levels across the electoral map, countering Trump’s claims that a Democratic administration would unleash violent anarchy.

“Joe has always been someone who was able to hold two thoughts together at the same time about law enforcement and racial justice,” said Senator Chris Coons of Delaware.

New York Times News Service