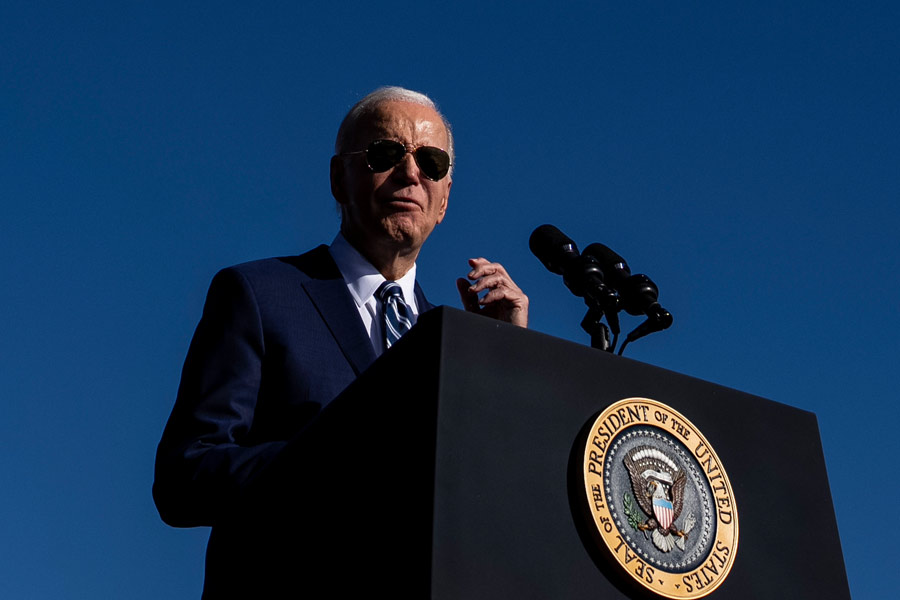

President Joe Biden could very well go down in history as the last American president born during World War II and shaped by a view of American power nurtured in the Cold War. No other leader on the world stage today can boast that they sat in the Israeli prime minister’s office 50 years ago with Golda Meir or discussed dismantling Soviet nuclear weapons with Mikhail Gorbachev.

So perhaps it is no surprise that the twin wars in which Biden has chosen to insert the United States — defending Ukraine as it tries to repel a nuclear-armed invader and now promising aid to Israel in wiping out the leadership of Hamas — have brought out a passion, emotion and a clarity that is usually missing from the president’s ordinarily flat and meandering speeches.

It rang out Thursday evening, as Biden combined the two struggles in his Oval Office address, declaring that while President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Hamas “represent different threats,” they “both want to completely annihilate a neighboring democracy.”

Throughout the speech, Biden toggled between the two crises, making the case that if the U.S. does not stand up in both conflicts the result will be “more chaos and death and more destruction.” That argument reflects his certainty that this is the moment he has trained for his entire political career, a point he often makes when challenged about his age.

His sense of mission explains why, at age 80, he has in the past eight months visited two countries in the midst of active wars. But at the same time he has married his public embraces with private cautions to U.S. allies, while carefully keeping American troops out of both conflicts — so far. He seems determined to prove that for all the critiques that the United States is a divided, declining power, it remains the only nation that can mold events in a world of unpredictable mayhem.

“When presidents get into their sweet spot you usually see and hear it, and in the past few weeks you have seen and heard it,” said Michael Beschloss, a historian and the author of “Presidents of War,” which traces the rocky history of Biden’s predecessors as they plunged into global conflicts, avoided a few and sometimes came to regret their choices.

Whether Biden can bring the American population along, however, is a more unsettled question than at any moment in his presidency and was the backdrop of his Oval Office address.

Polls show that a growing number of Americans are uneasy with the role of defender of the existing order, and the existing rules, that Biden describes as the essence of America. In the generation in which he grew up, his Thursday declaration that “American leadership is what holds the world together” would have been uncontroversial. Today it is a central point of debate, along with his insistence that “American alliances are what keep us, America, safe.”

For Biden, the democratic order is at risk if the rest of the world balks at toppling Hamas and neutralizing Russia. But he is finding that a far harder case to make now than in February 2022, when Putin tried a lightning-strike attack to overthrow an imperfect democracy in Ukraine and restore the Russian empire of Peter the Great.

The initial overwhelming support for Ukraine — one of the few issues that seemed to unify Democrats and Republicans — is clearly shattering, with a growing part of the Republican Party arguing that this is not America’s fight. The slog across the Donbas, and the prospect of a long conflict in which Putin is waiting to see if the U.S. will elect former President Donald Trump or someone of similar antipathy to the war effort only complicates the picture.

Now Biden’s whole-body embrace of Israel, so vivid in his seven-hour visit to Tel Aviv on Wednesday, may prove an equal challenge. After the horrific scenes of burned babies and kibbutz residents shot, raped or taken hostage by Hamas, he will almost certainly get the billions he is expected to ask for Thursday night to defend Israel. He has already invoked the history of Harry Truman’s momentous decision in 1948 to recognize Israel moments after it declared its independence, arguing in an Oct. 10 speech that 75 years later “we will make sure the Jewish and democratic state of Israel can defend itself today, tomorrow — as we always have.”

But already his administration is hearing strident criticism — some within his own administration — that he has tilted too far and done too little to restrain Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu from cutting off food, water and electricity in the Gaza Strip and from preparing for a ground invasion that could kill thousands more Palestinians. The critique of U.S. policy is most audible in some corners of the State Department, where there are already widespread reports of dissent that the U.S. support for Israel comes at the expense of protecting Palestinian civilians.

“I recognize the Israeli government’s right to respond and to defend themselves,” Josh Paul, a longtime diplomat in the State Department’s Bureau of Political and Military Affairs, which oversees much of the U.S. aid to Israel, told The Washington Post as he announced his resignation late Wednesday. “I guess I question how many Palestinian children have to die in that process.”

In private conversations and some social media chats, there is a growing wave of internal critique that Biden and his aides mistook a quieter moment in the Middle East before the Hamas invasion as an indication the status quo in Gaza and the West Bank was sustainable. And in private, even some aides around Biden say they fear the narrative around Israel and Hamas already is shifting, with memories of the horror of that bloody Saturday morning 12 days ago giving way to imagery of the destruction and desperation in Gaza.

Biden’s response is that experience has taught him that the best way to moderate Netanyahu’s behavior is to wrap him in support — and whisper a warning into his ear. He has made sure that members of his administration and allies are constantly in the country, and in Netanyahu’s war room, to keep the Israelis from rushing into a broad invasion.

Biden’s strategy has another element to it: While he is showing his support for both Ukraine and Israel, he has ruled out putting Americans directly into the fight. That is drawn from the experiences of Afghanistan and Iraq, where support for the U.S. effort was drained by the scenes of casualties that seemed increasingly pointless and by the failure of American ambitions — a reality Biden alluded to in Tel Aviv, Israel, when he spoke of the mistakes that grew from a post-Sept. 11 focus on vengeance.

On Thursday night, Biden made his most explicit case yet for why Americans, and the world, should rally behind four major goals. The first is to keep the aid flowing into Ukraine, so that Putin cannot wait out the West and strangle the country. The second goal for Biden is killing off Hamas. The third is to keep both wars from spreading.

And the final objective is to accomplish all this without bringing more death and misery to noncombatants caught in a world once again on fire.

The New York Times News Service