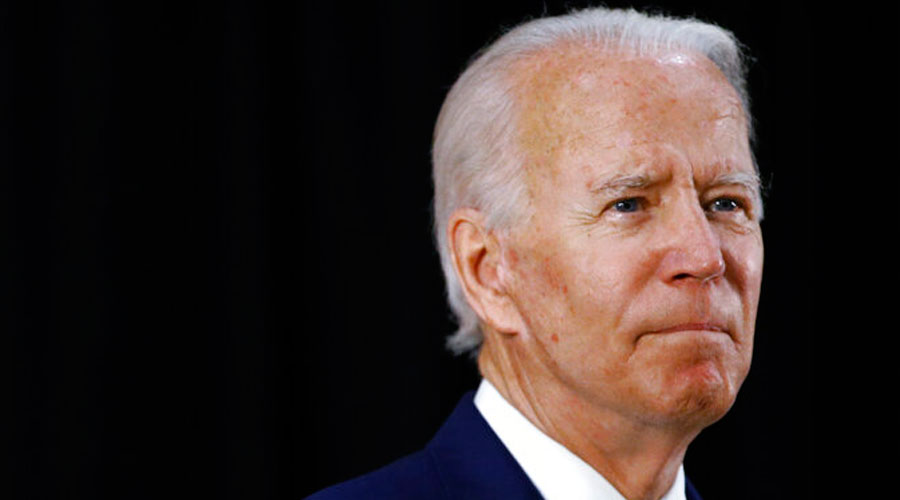

President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr, inheriting a collection of crises unlike any in generations, plans to open his administration with dozens of executive directives on top of expansive legislative proposals in a 10-day blitz meant to signal a turning point for a nation reeling from disease, economic turmoil, racial strife and now the aftermath of the assault on the Capitol.

Biden’s team has developed a raft of decrees that he can issue on his own authority after the inauguration on Wednesday to begin reversing some of President Trump’s most hotly disputed policies. Advisers hope the flurry of action, without waiting for Congress, will establish a sense of momentum for the new President even as the Senate puts his predecessor on trial.

On his first day in office alone, Biden intends a flurry of executive orders that will be partly substantive and partly symbolic. They include rescinding the travel ban on several predominantly Muslim countries, rejoining the Paris climate change accord, extending pandemic-related limits on evictions and student loan payments, issuing a mask mandate for federal property and interstate travel and ordering agencies to figure out how to reunite children separated from families after crossing the border, according to a memo circulated on Saturday by Ron Klain, his incoming White House chief of staff, and obtained by The New York Times.

The blueprint of executive action comes after Biden announced that he will push Congress to pass a $1.9-trillion package of economic stimulus and pandemic relief, signalling a willingness to be aggressive on policy issues and confronting Republicans from the start to take their lead from him.

He also plans to send sweeping immigration legislation on his first day in office providing a pathway to citizenship for 11 million people in the country illegally. Along with his promise to vaccinate 100 million Americans for the coronavirus in his first 100 days, it is an expansive set of priorities for a new President that could be a defining test of his deal-making abilities and command of the federal government.

For Biden, an energetic debut could be critical to moving the country beyond the endless dramas surrounding Trump. In the 75 days since his election, Biden has provided hints of what kind of President he hopes to be — focused on the big issues, resistant to the louder voices in his own party and uninterested in engaging in the Twitter-driven, minute-by-minute political combat that characterised the last four years and helped lead to the deadly mob assault on the Capitol.

But in a city that has become an armed camp since the January 6 attack, with inaugural festivities curtailed because of both the coronavirus and the threat of domestic terrorism, Biden cannot count on much of a honeymoon.

While privately many Republicans will be relieved at his ascension after the combustible Trump, the troubles awaiting Biden are so daunting that even a veteran of a half-century in politics may struggle to get a grip on the ship of state. And even if the partisan enmities of the Trump era ebb somewhat, there remain deep ideological divisions on the substance of Biden’s policies — on taxation, government spending, immigration, health care and other issues — that will challenge much of his agenda on Capitol Hill.

“You have a public health crisis, an economic challenge of huge proportions, racial, ethnic strife and political polarisation on steroids,” said Rahm Emanuel, the former Chicago mayor who served as a top adviser to Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. “These challenges require big, broad strokes. The challenge is whether there’s a partner on the other side to deal with them.”

Biden’s transition has been unlike that of any other new President, and so will the early days of his administration. The usual spirit of change and optimism that surrounds a newly elected President has been overshadowed by a defeated President who has refused to concede either the election or the spotlight.

Throughout his career, Biden has been a divining rod for the middle of his party, more moderate in the 1990s when that was in vogue and more liberal during the Obama era when the centre of gravity shifted.

He is driven less by ideology than by the mechanics of how to put together a bill that will satisfy various power centres. A “fingertip politician,” as he likes to put it, Biden is described by aides and friends as more intuitive about other politicians and their needs than was Obama, but less of a novel thinker.

Each morning, he receives a fat briefing book with dozens of tabs in a black binder and reads through it, but he prefers to interact with others. During the transition, he has conducted many of his briefings using Zoom.

He relishes freewheeling discussion, interrupting aides and chiding them for what he deems overly academic or elitist language. “Pick up your phone, call your mother, read her what you just told me,” he likes to say, according to aides. “If she understands, we can keep talking.” Aides made a point of editing out all abbreviations other than UN and NATO.

Biden will be the first true creature of Capitol Hill to occupy the White House since President Gerald R. Ford in the 1970s.

More than recent predecessors, he understands how other politicians think and what drives them. But his confidence that he can make deals with Republicans is born of an era when bipartisan cooperation was valued rather than scorned and he may find that today’s Washington has become so tribal that the old ways no longer apply.

“Joe Biden is somebody who understands how politicians work and how important political sensitivities are on each side, which is drastically different than President Obama,” said former Representative Eric Cantor of Virginia, who as the House Republican leader negotiated with Biden and came to like him.

“I would think there may be a time when Washington could get something done,” said Cantor. “At this point, I don’t know, the extreme elements on both sides are so strong right now, it’s going to be difficult.”

Biden’s determination to ask Congress for a broad overhaul of the nation’s immigration laws underscores the difficulties. In his proposed legislation, which he plans to unveil on Wednesday, he will call for a path to citizenship for about 11 million undocumented immigrants already living in the US, including those with temporary status and the so-called Dreamers, who have lived in the country since they were young children.

The bill will include increased foreign aid to ravaged Central American economies, provide safe opportunities for immigration for those fleeing violence, and increase prosecutions of those trafficking drugs and human smugglers.

But unlike previous Presidents, Biden will not try to win support from Republicans by acknowledging the need for extensive new investments in border security in exchange for his proposals, according to a person familiar with the legislation.

All of which explains why Biden and his team have resolved to use executive power as much as possible at the onset of the administration even as he tests the waters of a new Congress.

In his memo to Biden’s senior staff on Saturday, Klain underscored the urgency of the overlapping crises and the need for the new President to act quickly to “reverse the gravest damages of the Trump administration”.

While other Presidents issued executive actions right after taking office, Biden plans to enact a dozen on Inauguration Day alone, including the travel ban reversal, the mask mandate and the return to the Paris accord.

On Biden’s second day in office, he will sign executive actions related to the coronavirus pandemic aimed at helping schools and businesses to reopen safely, expand testing, protect workers and clarify public health standards.

On his third day, he will direct his cabinet agencies to “take immediate action to deliver economic relief to working families,” Klain wrote in the memo.

New York Times News Service