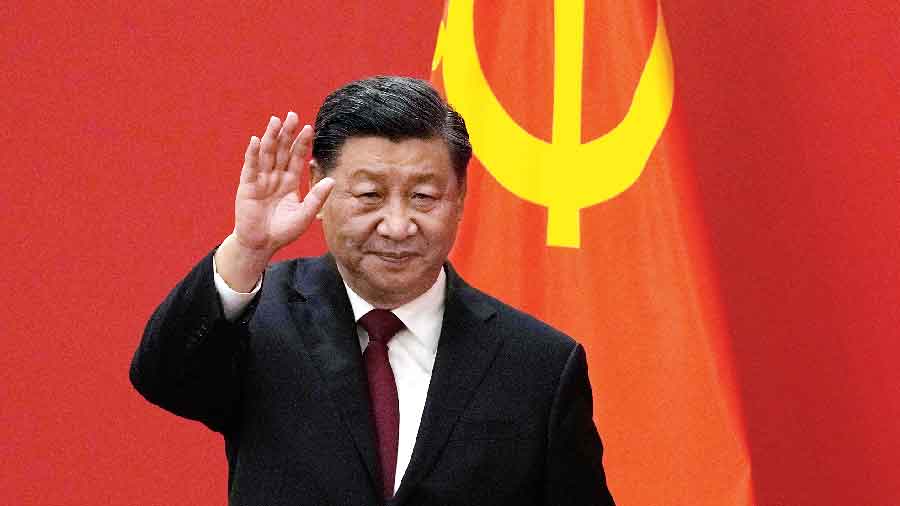

Just weeks after President Joe Biden and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping laid out competing visions of how the US and China are vying for military, technological and political pre-eminence, their first face-to-face meeting as top leaders will test whether they can halt a downward spiral that has taken relations to the lowest level since President Richard Nixon began the opening to Beijing half a century ago.

Their scheduled meeting on Monday in Indonesia will take place months after China brandished its military potential to choke off Taiwan, and the US imposed a series of export controls devised to hobble China’s ability to produce the most advanced computer chips — necessary for its newest military equipment and crucial to competing in sectors like artificial intelligence and quantum computing.

Compounding the tension is Beijing’s partnership with Moscow, which has remained steadfast even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet that relationship, denounced by the Biden administration, is so opaque that US officials disagree on its true nature.

Whether it’s a partnership of convenience or a robust alliance, Beijing and Moscow share a growing interest in frustrating the American agenda, many in Washington believe. In turn, many in China see the combination of the US export controls and Nato support for Ukraine as a foreshadowing of how Washington could try to contain China, and stymie its claims to Taiwan, a selfruled island.

This is in a sense the first superpower summit of the Cold War Version 2.0,” said Evan S. Medeiros, a Georgetown University professor who was President Barack Obama’s top adviser on Asia-Pacific affairs. “Will both leaders discuss, even implicitly, the terms of coexistence amid competition? Or, by default, will they let loose the dogs of unconstrained rivalry?”

Tamping down expectations about the summit with Xi, American officials recently told reporters that they expected no joint statement on points of agreement to emerge. Still, Washington will dissect what Xi says publicly and privately, especially about Russia, Ukraine and Taiwan.

This month, Xi told the visiting German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, that China opposes “the threat or use of nuclear weapons”, an oblique but unusually public reproach to Russian President Vladimir V. Putin’s sabre-rattling with tactical nuclear weapons.

If Xi cannot say something similar with an American President next to him, one senior administration official noted, it will be telling. China sees Russia as a vital counterweight to western power, and Xi may hesitate to criticise Putin in front of Biden.

If Putin used nuclear weapons, he would become “the public enemy of humankind, opposed by all countries, including China”, said Hu Wei, a foreign policy scholar in Shanghai. But, he added: “If Putin falls, the United States and the West will then focus on strategic containment of China.”

Xi and Biden have talked on the phone five times in the past 18 months. This will be different: For the first time since assuming the presidency, Biden will “sit in the same room with Xi Jinping, be direct and straightforward with him as he always is, and expect the same in return from Xi”, Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, said at a White House briefing on Thursday.

“There just is no substitute for this kind of leader-to-leader communication in navigating and managing such a consequential relationship,” Sullivan said.

During the past three decades, trips by American Presidents to Beijing and Chinese Presidents to Washington became relatively commonplace. Testy exchanges over disputes were often balanced by promises to cooperate on areas of mutual interest, whether climate change or containing North Korea’s nuclear programme. For now, it is hard to imagine a meeting taking place in either capital, especially with China still under heavy Covid controls.

Summits on neutral ground, like this one in Bali ahead of the Group of 20 meeting of leaders, have an increasingly Cold War feel: more about managing potential conflict than finding common ground. The rancorous distrust means that even short-term stabilisation and cooperation on shared challenges, like stopping pandemics, could be fragile.

Neither side calls it a Cold War, a term evoking a world divided between western and Soviet camps bristling with nuclear arsenals. And the differences are real between that era and this one, with its vast trade flows and technological commerce between China and western powers.

The Apple iPhone and many other staples of American life are assembled almost entirely in China. Instead of trying to build a formal bloc of allies as the Soviets did, Beijing has sought to influence nations through major projects that create dependency, including wiring them with Chinese-made communications networks.

Even so, the declarations surrounding Xi’s appointment to a third term and Biden’s new national security, defence and nuclear strategies have described an era of growing global uncertainty heightened by competition — economic, military, technological, political — between their countries.

The anxieties have been magnified by China’s plans to expand and modernise its still relatively limited nuclear arsenal to one that could reach at least 1,000 warheads by 2030, according to the Pentagon. China sees threats in American-led security initiatives, including proposals to help build nuclear-powered submarines for Australia.

“It may not be the Cold War, with a capital C and capital W, as in a replay of the US-Soviet experience,” Professor Medeiros said. But, he added, “because of China’s substantial capabilities and its global reach, this cold war will be more challenging in many ways than the previous one.”

Despite their differences, Biden and Xi want to avoid pent-up tensions exploding into a crisis that could wreak economic havoc.

“I’ve told him: I’m looking for competition, not — not conflict,” Biden told reporters at the White House on Wednesday about his relationship with Xi. Their ties go back more than a decade, to when both were Vice-Presidents.

Biden said that he and Xi may discuss “what he believes to be in the critical national interests of China, what I know to be the critical interests of the United States, and to determine whether or not they conflict with one another. And if they do, how to resolve it and how to work it out.”

Ahead of the meeting, Xi has also put on a somewhat friendlier demeanour. He told the National Committee on US-China Relations that he wants to “find the right way to get along”.

New York Times News Service