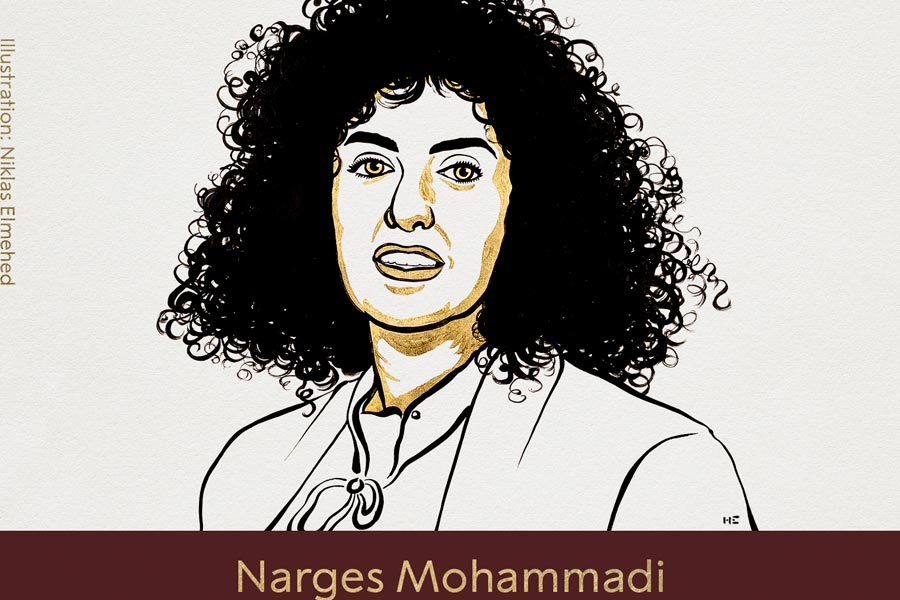

Narges Mohammadi, a jailed Iranian activist, was named the recipient of the 2023 Nobel Peace Prize on Friday “for her fight against the oppression of women in Iran and her fight to promote human rights and freedom for all”.

The closely watched announcement, made by the Norwegian Nobel Committee in Oslo, comes after women-led protests in Iran that convulsed the country following the death in custody of a 22-year-old who had been arrested by the country’s morality police.

Hundreds were killed in the ensuing government crackdown, including at least 44 minors, while around 20,000 Iranians were arrested, the United Nations calculated.

“This year’s peace prize also recognises the hundreds of thousands of people who, in the preceding year, have demonstrated against Iran’s theocratic regime’s policies of discrimination and oppression targeting women,” the committee said. “The motto adopted by the demonstrators — ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ — suitably expresses the dedication and work of Narges Mohammadi”.

There were 351 candidates for the prize this year, according to the Nobel committee, the second-highest number ever. Mohammadi joins 137 laureates named since the prize’s inception in 1901, a list that includes US President Barack Obama; Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk; and Mother Teresa.

The committee has been known to make surprise picks, but speculation about this year’s prize had focused on activists for women’s rights — including Mohammadi and Mahbouba Seraj of Afghanistan — and on climate change and the war in Ukraine.

Last year, the Peace Prize was shared by democracy activists from Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, in what was widely seen as a rebuke to President Vladimir Putin of Russia and the Kremlin’s increasing repression.

The awards — to Memorial, a Russian organisation; the Centre for Civil Liberties in Ukraine; and Ales Bialiatski, a jailed Belarusian activist — highlighted the long shadow of the Soviet past and the efforts of former Soviet states to break free of Russian dominance.

Mohammadi, the most prominent human rights activist in Iran, has dedicated her career to fighting government repression with a focus on women’s rights. She is currently serving a 10-year jail sentence in Tehran’s Evin Prison for “spreading anti-state propaganda”.

Her 30 years of activism to peacefully bring grassroots change to Iran through education, advocacy and civil disobedience and to strengthen civil society has come with a hefty price: her liberty, her health and separation from her husband, children and parents.

Even from inside prison, Mohammadi, 51, has been one of the most outspoken critics of Iran’s government. She has organised protests and sit-ins as part of the uprising, led by women, that rocked Iran last year, written guest essays and organised weekly workshops for women inmates about their rights.

“The global support and recognition of my human rights advocacy makes me more resolved, more responsible, more passionate and more hopeful,” Mohammadi said in a written statement to The New York Times. “I also hope this recognition makes Iranians protesting for change stronger and more organised. Victory is near.”

Mohammadi’s husband and fellow rights activist, Taghi Rahmani, and her twin 16-year-old children, Ali and Kiana, live in exile in France. She has not seen her children in eight years.

Rahmani said this week that the Nobel Prize would be a nod to his wife’s decades of work from the ground in Iran, but that the recognition would be bigger than Mohammadi.

“It is also a prize for all the human rights activists who have been fighting for change in Iran for many decades in a society that has unjust laws,” Rahmani said in an interview. “It is a recognition of the Women, Life, Freedom movement in Iran.”

Mohammadi is the second Iranian woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Shirin Ebadi, a human rights lawyer and Mohammadi’s longtime mentor and colleague received the award in 2003. The two women worked together in Iran at the Defenders of Human Rights Centre, founded by Ebadi in 2001. The organisation was shut down in a violent raid in 2009.

Mohammadi was born in 1972 in the central Iranian city of Zanjan to a middle-class family, seven years before the Iranian Revolution. Her path to activism began with two childhood memories: her mother stuffing a red plastic shopping basket with fruit for weekly prison visits with her brother, and her mother sitting on the floor near the television screen to hear the names of prisoners executed each day.

She studied physics at a university in Qazvin, Iran, where she quickly became involved in activism, founding a women’s hiking group and another group focused on civic engagement. She met her husband, a well-known figure in Iran’s intellectual circles when she attended an underground class that he taught on civil society. The couple rotated in and out of prison for most of their marriage and have not been together as a family unit with their children since they were toddlers.

Mohammadi has earned many accolades, including the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award at its annual gala in New York this year. The UN also named her as one of the three recipients of its World Press Freedom Prize in May.

“I have to keep my eyes on the horizon and the future even though the prison walls are tall and near and blocking my view,” she said in an interview with the Times this year.

New York Times News Service