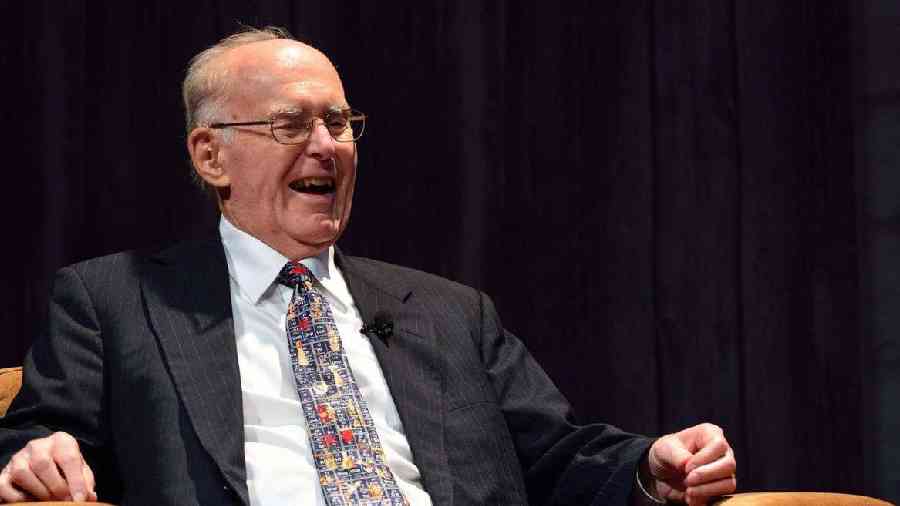

Gordon E. Moore, a co-founder and former chairman of Intel Corporation, the California semiconductor chip maker that helped give Silicon Valley its name, achieving the kind of industrial dominance once held by the giant American railroad or steel companies of another age, died on Friday at his home in Hawaii. He was 94. His death was announced by Intel.

Along with a handful of colleagues, Moore could claim credit for bringing laptop computers to hundreds of millions of people and embedding microprocessors into everything from bathroom scales, toasters and toy fire engines to cellphones, cars and jets.

Moore, who had wanted to be a teacher but could not get a job in education and later called himself the Accidental Entrepreneur, became a billionaire as a result of an initial $500 investment in the fledgling microchip business. And it was he, his colleagues said, who saw the future.

In 1965, in what became known as Moore’s Law, he predicted that the number of transistors that could be placed on a silicon chip would double at regular intervals for the foreseeable future, thus increasing the data-processing power of computers exponentially.

He added two corollaries later: The evolving technology would make computers more and more expensive to build, yet consumers would be charged less and less for them because so many would be sold. Moore’s Law held up for decades.

Through a combination of Moore’s brilliance, as well as that of his partner and Intel co-founder, Robert Noyce, the two assembled a group widely regarded by many as among the boldest and most creative technicians of the high-tech age.

New York Times News Service