“I love myself!” the group of mostly black children shouted in unison. “I love my hair, I love my skin!” When it was time to settle down, their teacher raised her fist in a black power salute. The students did the same, and the room hushed. As children filed out of the cramped school auditorium on their way to class, they walked by posters of Colin Kaepernick and Harriet Tubman.

It was a typical morning at Ember Charter School in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, an Afrocentric school that sits in a squat building on a quiet block in a neighbourhood long known as a centre of black political power.

Though New York City has tried to desegregate its schools in fits and starts since the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the school system is now one of the most segregated in the nation. But rather than pushing for integration, some black parents in Bedford-Stuyvesant are choosing an alternative: schools explicitly designed for black children.

Afrocentric schools have been championed by black educators who had traumatic experiences with integration as far back as the 1960s and by young black families who say they recently experienced coded racism and marginalisation in integrated schools. Both groups have been disappointed by decades of efforts to address inequities in America’s largest school system.

“Some of us are pro-integration, some of us are anti- and others are ambivalent,” said Lurie Daniel Favors, a member of Parenting While Black, a newly formed group of Brooklyn parents. “Even if integrated education worked perfectly — and our society spent the past 60-plus years trying — it’s still not giving black children the kind of education necessary to create the solutions our communities need.”

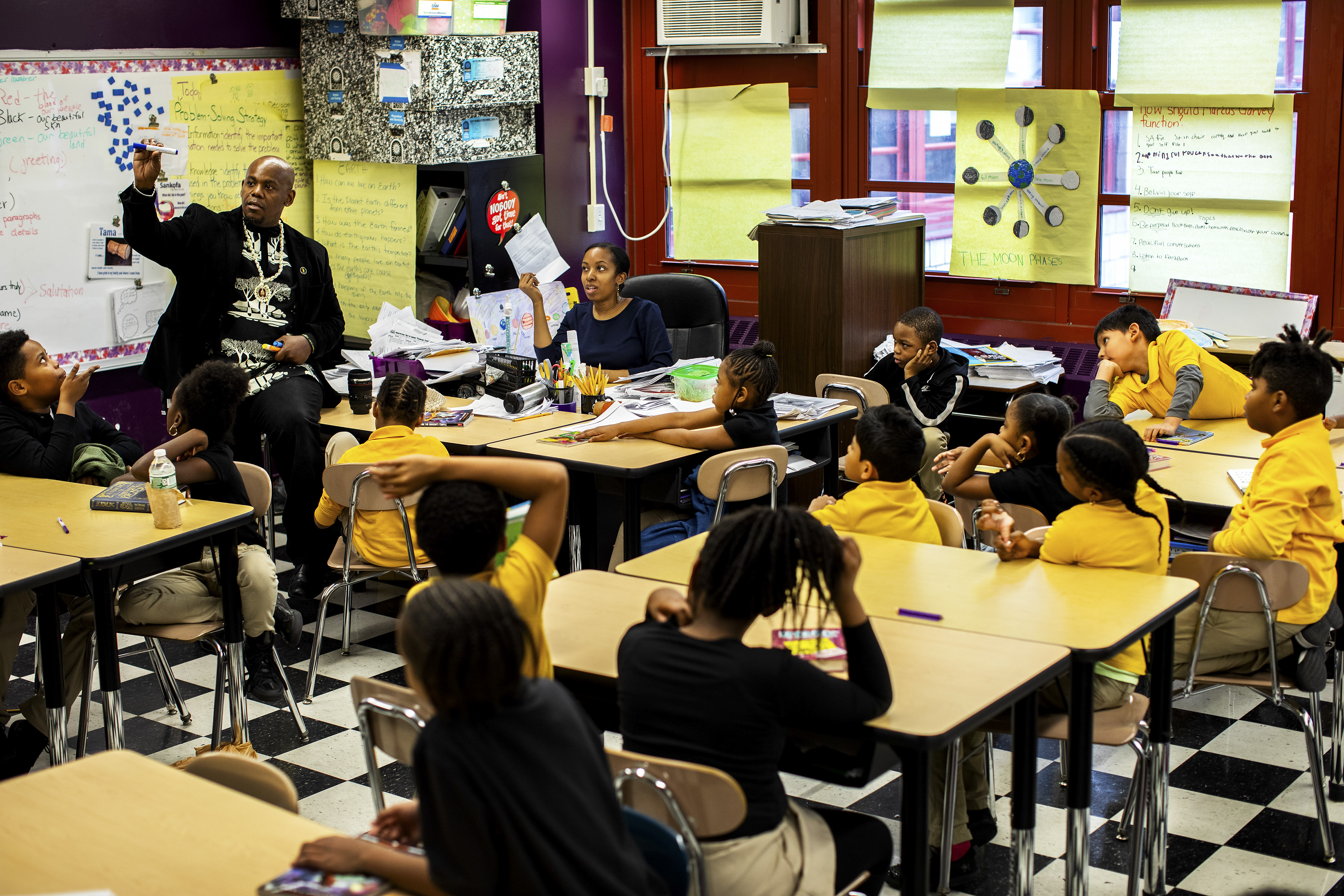

Rafiq Kalam al-Din II, the founder of Ember Charter School, teaches a class in Brooklyn. The New York Times

Children of any race may apply to an Afrocentric school, though they are overwhelmingly black. Some have sizable numbers of Hispanic students — Ember, which goes from kindergarten to eighth grade and is about a third Hispanic, incorporates Spanish into the students’ morning affirmation — but the schools typically have few or no white applicants.

The half-dozen or so Afrocentric schools in central Brooklyn, in which about 2,300 children are enrolled, include private and charter schools, which require applications and do not admit students through geographical zones, and public high schools, which are also unzoned. The schools are run and staffed mostly by people of colour, and tend to have high graduation rates and standardised test scores at or above the city average.

With the city’s approval, any principal can adopt a black-centric curriculum — with black teachers, and a focus on black culture in literature, history and art classes — as long as the school complies with state educational standards.

Though Afrocentric schools have a uniquely comprehensive approach, many of New York’s 1,800 public schools have specialised themes. There are engineering, math and culinary schools. Others have Albanian, Urdu or Bengali bilingual programmes.

Afrocentric schools aim to empower black children in ways that traditional schools in America historically have not. Though integration advocates want the same, some parents and educators across the country believe high-quality Afrocentric schools can achieve that goal in a different way — by asserting black power, pride and excellence close to home.

And though a recent study found that some Afrocentric charter schools are low-performing, they remain popular among parents and many educators. Milwaukee and Chicago have prominent black-centric charter schools. In Georgia, some black parents have decided to home-school their children to help ensure they learn about black history. New Afrocentric public schools and programs have sprouted in Washington, D.C., and Oakland, California.

But even as the concept is spreading, decades of research has shown that integration can redistribute resources across schools and thus improve academic performance, and experts warned that abandoning integration could backfire. “Segregation leads to inequality,” said Andre Perry, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. “You can’t just do that away. If you’re going to ignore this issue, it will come back to haunt you.”

Students at Ember Charter School decorate the hallways with photographs of black and Hispanic artists from Brooklyn. The New York Times

Richard Carranza, the city’s schools chancellor, said he is eager to expand a debate he helped start about stark inequalities in schools — even if some black parents don’t agree that integration is the answer.

“Often when you talk about integration, it’s about taking black kids out of their schools and sending them into white schools,” he said in an interview. “Rarely is it about, ‘How do you have other kids come into traditionally black schools and find value?’

“If there’s a school that says that’s what we want to focus on,” he said, referring to Afrocentric schools, “I think we should be very supportive of that.”

Bedford-Stuyvesant’s traditional public schools — most of which do not have expressly Afrocentric classes — are overwhelmingly black and mostly low-performing. About three-quarters of the neighbourhood’s parents, including many middle-class black parents, send their children to schools in different districts. In interviews, some parents said they would be more likely to stay if there were more Afrocentric options.

As school segregation has become entwined with New York City’s broader reckoning with inequality, some districts recently adopted modest desegregation plans — changing school zones and setting aside seats for low-income children — that have made some schools marginally more diverse.

But fraught debates have often revolved around the hopes and anxieties of white parents in middle-class, diverse neighbourhoods. Several meetings on the Upper West Side and in downtown Brooklyn have included white parents screaming and sobbing about the prospect of their children losing a seat in a classroom they had thought was guaranteed. Bedford-Stuyvesant offers a glimpse of how the rest of the city is grappling with a school system that produces winners and losers.

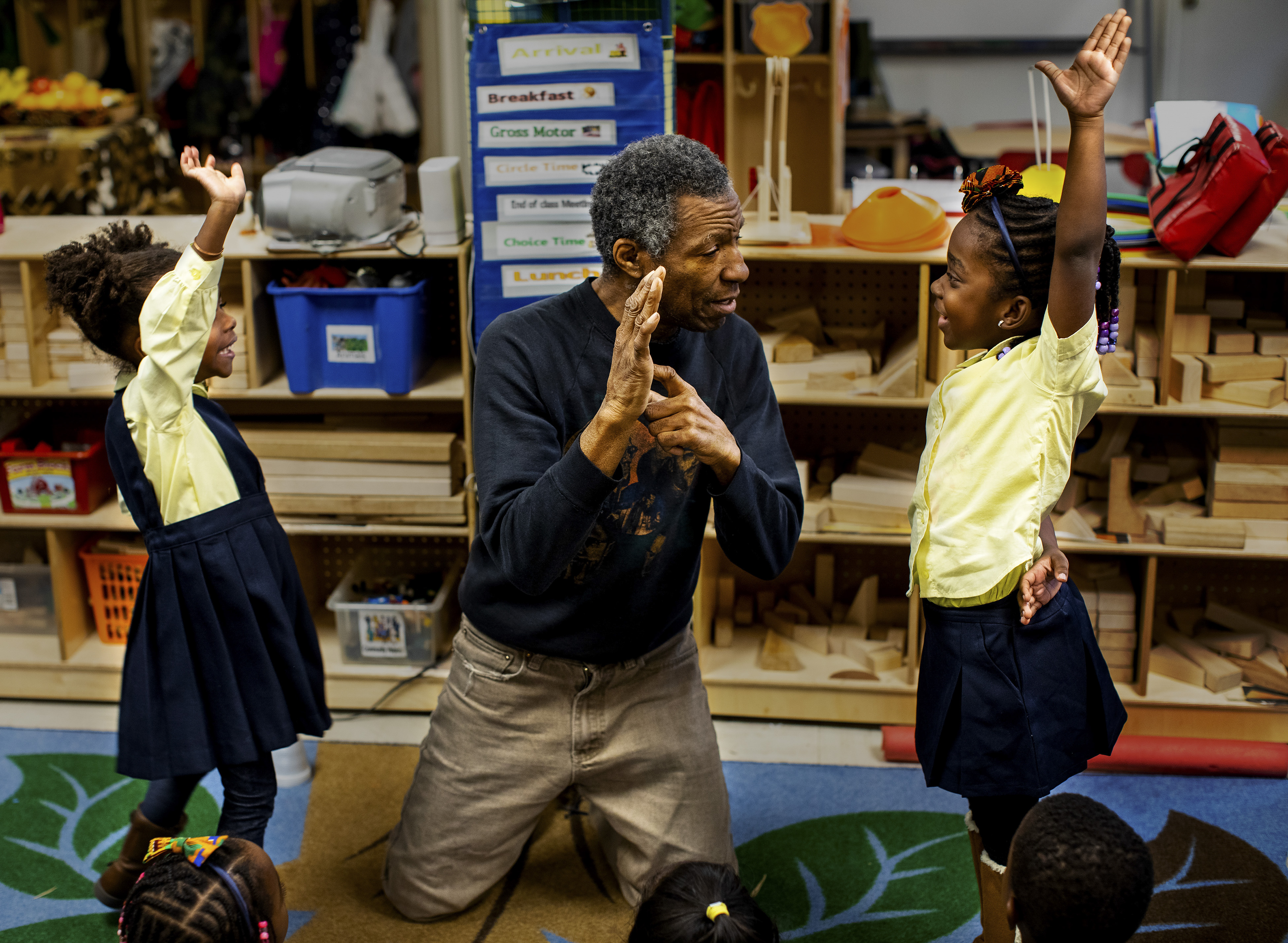

Thomas Lewis, a martial arts instructor, teaches a lesson at Little Sun People, a private preschool in Brooklyn. The New York Times

‘I’m going to make a school’

Kara Benton-Smith, a mother of two in Bedford-Stuyvesant, found her perfect school when she opened the front door of Little Sun People, a private preschool. She saw a painting of a black woman in the hallway, and it felt like home.

Soon, Benton-Smith’s daughter was taking school trips to the Apollo Theater and reciting the principles of Kwanzaa. For her toddler, “it was very matter-of-fact that being black is cool,” Benton-Smith said.

Many of the Brooklyn parents pushing for Afrocentric schools first connected at Little Sun People, and their movement has grown in part out of the one-room school on Fulton Street.

The school’s founder, Fela Barclift, said she has spent years telling parents that they can demand more Afrocentric public schools when their children graduate to kindergarten.

“When you leave here and you’re going out there, that’s what you’re looking for,” said Barclift, known to all as Mama Fela. “And if you don’t find it, then you are going to put pressure.”

Barclift opened her school on an empty floor of her Bedford-Stuyvesant brownstone in 1981, long before nearby homes started to sell for millions of dollars. She, like Benton-Smith, could not find a preschool that reflected “blackness or African heritage,” she said.

“I was like, ‘You know what, I’m going to make a school in here,'’ Barclift said. She brought in a Swahili teacher and spent hours hunched over children’s books with a brown crayon, coloring in the faces and hair of the white characters.

Little Sun People represents an alternative to a type of integration Barclift has hoped to avoid since she was a child.

In the 1960s, her two younger siblings were bused from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Bay Ridge, then a largely white Brooklyn neighborhood, where they were spat on and called names. “School was a tragic experience for them,” Barclift said.

At Little Sun People, she said, “you see you.”

Toddlers at Little Sun People, a private preschool in Brooklyn, did an art project based on masks from Ivory Coast. The New York Times

‘Not all boats are rising’

Decades after Barclift wrestled with the impact of integration on her family, Benton-Smith and the other members of Parenting While Black are similarly ambivalent about what integration can offer their children.

They don’t believe integration can succeed unless all schools are responsive to the needs of black and Hispanic students — which they say requires new curriculums, more teachers of color, and a strong emphasis on culture and identity.

“Even in a school that’s integrated, even in a school that’s high-performing, not all boats are rising,” said Mutale Nkonde, another member of the group, whose children have attended integrated schools. “When I’m looking at integration, I’m actually seeing it as a threat to resources being visited on your child if they don’t fall within a certain subset.”

When Rafiq Kalam al-Din II created Ember, he wanted to avoid that dynamic.

“Who’s mad at diversity? Nobody’s mad at more different people getting along — that’s a beautiful thing,” he said. “But if we use it as a strategy for solving the educational crisis in this community, it’s totally misapplied.”

Perry of the Brookings Institution believes that integration advocates and skeptics alike share the same elusive goal.

“I think most people who want integration are really interested in breaking up the structures of inequality,” he said.

c.2019 New York Times News Service