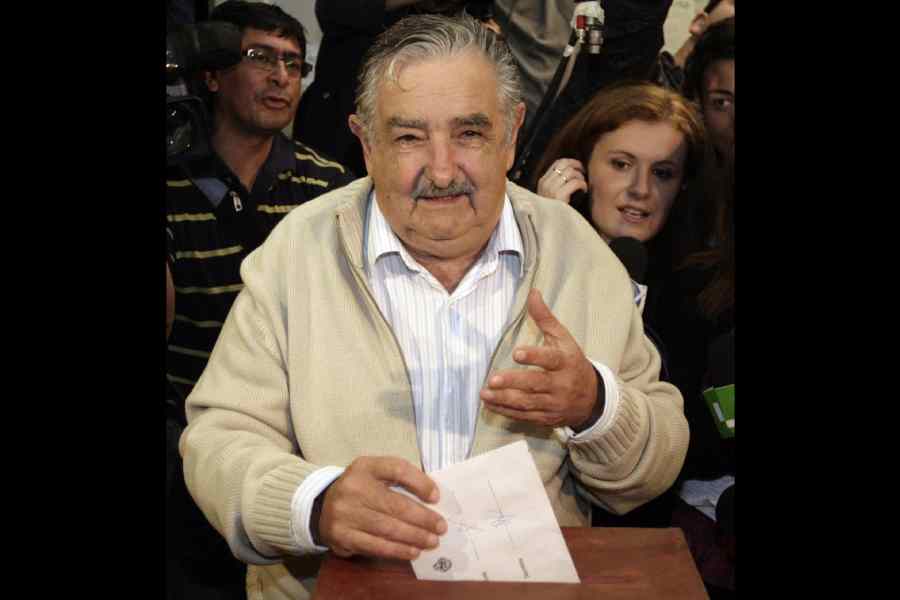

A decade ago, the world had a brief fascination with José Mujica. He was the folksy President of Uruguay who had shunned his nation’s presidential palace to live in a tiny tin-roof home with his wife and three-legged dog.

In speeches to world leaders, interviews with foreign journalists and documentaries on

Netflix, Pepe Mujica, as he is universally known, shared countless tales from a life story fit for film. He had robbed banks as a Leftist urban guerrilla; survived 15 years as a prisoner, including by befriending a frog while kept in a hole in the ground; and helped lead the transformation of his small South American nation into one of the world’s healthiest and most socially liberal democracies.

But Mujica’s legacy will be more than his colourful history and commitment to austerity. He became one of Latin America’s most influential and important figures in large part for his plain-spoken philosophy on the path to a better society and happier life.

Now, as Mujica puts it, he is fighting death. In April, he announced he would undergo radiation for a tumour in his oesophagus. At 89 and already diagnosed with an autoimmune disease, he admitted the path to recovery would be arduous.

Last week, I travelled to the outskirts of Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, to visit Mujica at his three-room home, full of books and jars of pickling vegetables, on the small farm where he has grown chrysanthemums for decades. As the sun set on a winter day, he was bundled in a winter jacket and wool hat in front of a wood stove. The treatment had left him weak and hardly eating.

“You’re talking to a strange old man,” he said, leaning in to look at me closely, a glisten in his eye. “I don’t fit in today’s world.”

And so we began.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Q: How is your health?

Mujica: They did radiation treatment on me. My doctors said it went well, but I’m broken.

(Unprompted.)

I think that humanity, as it’s going, is doomed.

Q: Why do you say that?

Mujica: We waste a lot of time uselessly. We can live more peacefully. Take Uruguay. Uruguay has 3.5 million people. It imports 27 million pairs of shoes. We make garbage and work in pain. For what?

You’re free when you escape the law of necessity — when you spend the time of your life on what you desire. If your needs multiply, you spend your life covering those needs.

Humans can create infinite needs. The market dominates us, and it robs us of our lives.

Humanity needs to work less, have more free time and be more grounded. Why so much garbage? Why do you have to change your car? Change the refrigerator?

There is only one life and it ends. You have to give meaning to it. Fight for happiness, not just for wealth.

Q: Do you believe that humanity can change?

Mujica: It could change. But the market is very strong. It has generated a subliminal culture that dominates our instinct. It’s subjective. It’s unconscious. It has made us voracious buyers. We live to buy. We work to buy. And we live to pay. Credit is a religion. So we’re kind of screwed up.

Q: It seems you don’t have much hope

Mujica: Biologically, I do have hope, because I believe in man. But when I think about it, I’m pessimistic.

Yet your speeches often have a positive message.

Because life is beautiful. With all its ups and downs, I love life. And I’m losing it because it’s my time to leave. What meaning can we give to life? Man, compared to other animals, has the ability to find a purpose.

Or not. If you don’t find it, the market will have you paying bills the rest of your life.

If you find it, you will have something to live for. Those who investigate, those who play music, those who love sports, anything. Something that fills your life.

Q: Why did you choose to live in your own home as President?

Mujica: The cultural remnants of feudalism remain. The red carpet. The bugle. Presidents like to be praised.

I once went to Germany and they put me in a Mercedes-Benz. The door weighed about 3,000 kilos. They put 40 motorcycles in front and another 40 in back. I was ashamed.

We have a house for the President. It’s four stories. To have tea you have to walk three blocks. Useless. They should make it a high school.

Q: How would you like to be remembered?

Mujica: Ah, like what I am: a crazy old man.

Q: That’s all? You did a lot

Mujica: I have one thing. The magic of the word.

The book is the greatest invention of man. It’s a shame that people read so little. They don’t have time.

Nowadays people do much of their reading on phones.

Four years ago, I threw mine away. It made me crazy. All day talking nonsense.

We must learn to speak with the person inside us. It was him who saved my life. Since I was alone for many years, that has stayed with me.

When I’m in the field working with the tractor, sometimes I stop to see how a little bird constructs its nest. He was born with the programme. He’s already an architect. Nobody taught him. Do you know the hornero bird? They are perfect bricklayers.

I admire nature. I almost have a sort of pantheism. You have to have the eyes to see it.

The ants are one of the true communists out there. They are much older than us and they will outlive us. All colony beings are very strong.

Q: Going back to phones: Are you saying they are too much for us?

Mujica: It’s not the phone’s fault. We’re the ones who are not ready. We make a disastrous use of it.

Children walk around with a university in their pocket. That’s wonderful. However, we have advanced more in technology than in values.

Q: Yet the digital world is where so much of life is now lived

Mujica: Nothing replaces this. (He gestures at the two of us talking.) This is nontransferable. We’re not only speaking through words. We communicate with gestures, with our skin. Direct communication is irreplaceable.

We are not so robotic. We learned to think, but first we are emotional beings. We believe we decide with our heads. Many times the head finds the arguments to justify the decisions made by the gut. We’re not as aware as we seem.

And that’s fine. That mechanism is what keeps us alive. It’s like the cow that follows what’s green. If there is green, there is food. It’s going to be tough to give up who we are.

Q: You have said in the past that you don’t believe in God. What is your view of God in this moment of your life?

Mujica: Sixty per cent of humanity believes in something, and that must be respected. There are questions without answers. What is the meaning of life? Where do we come from? Where are we going?

We don’t easily accept the fact that we are an ant in the infinity of the universe. We need the hope of God because we would like to live.

Q: Do you have some kind of God?

Mujica: No. I greatly respect people who believe. It’s like a consolation when faced with the idea of death.

Because the contradiction of life is that it is a biological programme designed to struggle to live. But from the moment the programme starts, you are condemned to die.

Q: It seems biology is an important part of your worldview

Mujica: We are interdependent. We couldn’t live without the prokaryotes we have in our intestine. We depend on a number of bugs that we don’t even see.

Life is a chain and it is still full of mysteries.

I hope human life will be prolonged, but I’m worried. There are many crazy people with atomic weapons. A lot of fanaticism. We should be building windmills. Yet we spend on weapons.

What a complicated animal man is. He’s both smart and stupid.

New York Times News Service