In January, at a restaurant in Guangzhou, China, one diner infected with the novel coronavirus but not yet feeling sick, appeared to have spread the disease to nine other people. One of the restaurant’s air-conditioners apparently blew the virus particles around the dining room.

There were 73 other diners who ate that day on the same floor of the five-story restaurant, and the good news is they did not become sick. Neither did the eight employees who were working on the floor at the time.

Chinese researchers described the incident in a paper that is to be published in the July issue of the Emerging Infectious Diseases, a journal published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The field study has limitations. The researchers, for example, did not perform experiments to simulate the airborne transmission.

That outbreak illustrates some of the challenges that restaurants will face when they try to reopen. Ventilation systems can create complex patterns of air flow and keep viruses aloft, so simply spacing tables 6 feet apart — the minimum distance that the CDC advises you keep from other people — may not be sufficient to safeguard restaurant patrons.

The social nature of dining out could increase the risk. The longer people linger in a contaminated area, the more virus particles they would likely inhale. Eating is also one activity that cannot be accomplished while wearing a mask. Virus-laden droplets can be expelled into the air through breathing and talking, not just through coughs and sneezes.

As the CDC now advises, “Avoid large and small gatherings in private places and public spaces, such a friend’s house, parks, restaurants, shops, or any other place.”

On the other hand, all of the people who became sick at the restaurant in China were either at the same table as the infected person or at one of two neighboring tables. The fact that people farther away remained healthy is a hopeful hint that the coronavirus is primarily transmitted through larger respiratory droplets, which fall out of the air more quickly than smaller droplets known as aerosols, which can float for hours.

“I think it’s a well-done study with the limitations of being a field study,” said Werner E. Bischoff, the medical director of infection prevention and health system epidemiology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine in North Carolina. Bischoff was not involved with the research.

On Jan. 24, a family went to lunch at the restaurant in Guangzhou, a sprawling metropolis in southern China located 80 miles from Hong Kong.

The family had left Wuhan, 520 miles to the north and the hot spot of the initial coronavirus outbreak, one day before Chinese officials imposed a lockdown on the city and the surrounding province of Hubei to slow the spread of the disease.

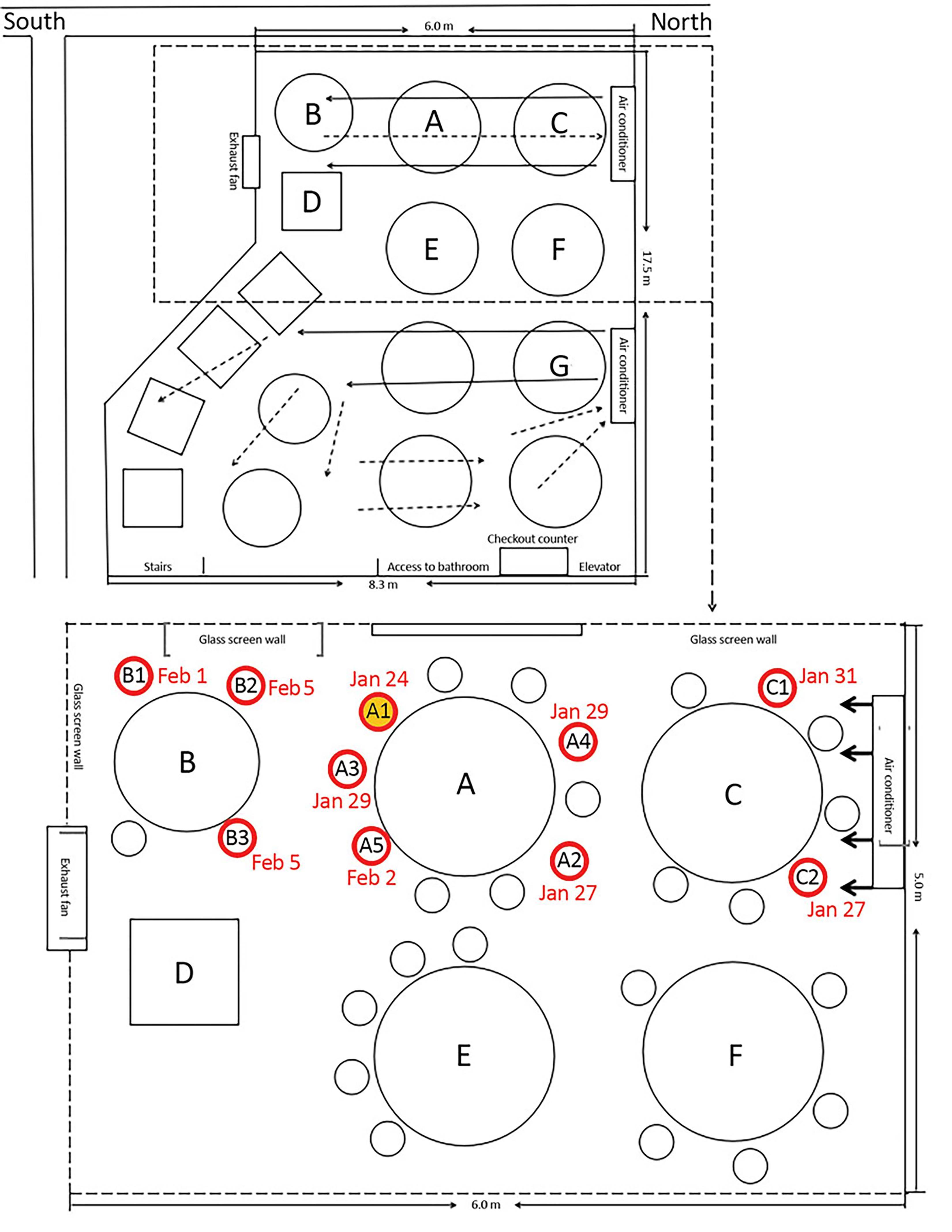

In a photo provided by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a diagram of the arrangement of a restaurant’s tables and air conditioning airflow at site of an outbreak of coronavirus in Guangzhou, China. Red circles indicate the seating of future case-patients; the yellow-filled red circle indicates the index case, or first-documented, patient. A limited study by Chinese researchers suggests the role played by air currents in spreading the illness in enclosed spaces. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention via The New York Times)

At lunch, the five members of the family — designated Family A in the paper — appeared healthy. But later in the day, one of them, a 63-year-old woman, experienced a fever and a cough and went to the hospital where she tested positive for the coronavirus.

Within two weeks, nine others who ate lunch on that floor of the Guangzhou restaurant that day also tested positive. Four were relatives of the first infected woman. They could have been infected outside of the restaurant.

But for the other five, the restaurant appears to have been the source of the virus.

Family A’s table was on the west side of the 1,500-square foot dining room, between tables where two unrelated families, B and C, were also having lunch. Family B and Family A overlapped for a period of 53 minutes, and three of its members — a couple and their daughter — became sick. Family C sat next to Family A at the other neighboring table along the same side of the room, overlapping for 73 minutes, and two of its members — a mother and her daughter — became ill.

An air-conditioning unit next to Family C blew air in the southward direction across all three tables; some of the air likely bounced off the wall, back in the direction of Family C.

Because the coronavirus had not yet spread widely beyond Wuhan, public health officials were able to trace the recent contacts of Families B and C and determine that the restaurant was the only likely place where they would have crossed paths with the virus.

The researchers did not state in the paper whether any of the other diners who did not contract the coronavirus were members of the three affected families or if they were all customers at 12 other tables. The 73 people were quarantined for 14 days and did not develop symptoms.

“We conclude that in this outbreak, droplet transmission was prompted by air-conditioned ventilation,” the authors wrote. “The key factor for infection was the direction of the airflow.”

Harvey V. Fineberg, who leads the Standing Committee on Emerging Infectious Diseases and 21st Century Health Threats at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, described the report as “provocative and eye-opening.”

He said restaurants should be mindful of the direction of airflow in arranging tables. Germicidal ultraviolet lights could also be installed to destroy floating virus particles, Fineberg said. And the paper’s findings could have implications beyond restaurants.

“It’s illuminating for the kind of thing we need to keep learning about as we try to configure safe work spaces,” Fineberg said. “Not just safe restaurant and entertainment venues but where you go to work.”