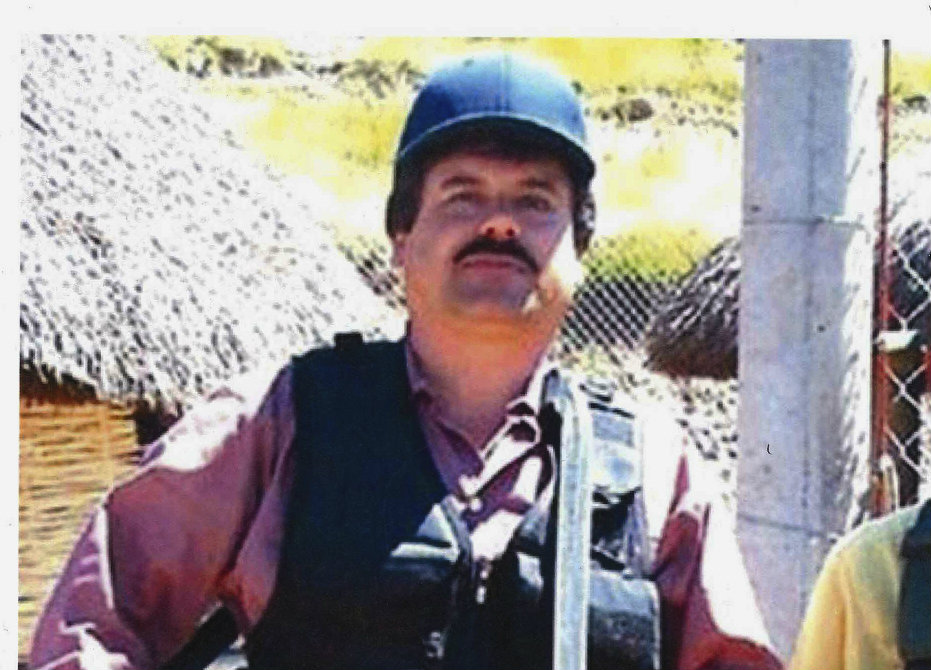

In February 2010, an undercover FBI agent met in a Manhattan hotel with a Colombian info-tech expert who had been the target of a sensitive investigation. The IT specialist, Cristian Rodriguez, had recently developed an extraordinary product: an encrypted communications system for Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the Mexican drug lord known as El Chapo.

Posing as a Russian mobster, the undercover agent told Rodriguez he was interested in acquiring a similar system. He wanted a way — or so he said — to talk with his associates without law enforcement listening in.

So began a remarkable clandestine operation that in a little more than a year allowed the FBI to crack Guzmán’s covert network and ultimately capture as many as 200 digital phone calls of him chatting with his underlings, planning ton-sized drug deals and even discussing illicit payoffs to Mexican officials. The hours of Guzmán speaking openly about the innermost details of his empire not only represented the most damaging evidence introduced so far at his drug trial in New York, but were also one of the most extensive wiretaps of a criminal defendant since Mafia boss John Gotti was secretly recorded in the Ravenite Social Club.

The existence of the scheme — and several of the phone calls — were revealed for the first time on Tuesday as Stephen Marston, an FBI agent who helped to run the operation, appeared as a witness at Guzmán’s trial. In a day of testimony, Marston told jurors that the crucial step in the probe was recruiting Rodriguez to work with US authorities.

In a daring move that placed his life in danger, the IT consultant eventually gave the FBI his system’s secret encryption keys in 2011 after he had moved the network’s servers from Canada to the Netherlands during what he told the cartel’s leaders was a routine upgrade.

Since the trial began in November in US District Court in Brooklyn, the prosecution has more or less presented typical evidence: surveillance photos, ledgers documenting drug deals and testimony from a sprawling cast of Guzmán’s former lieutenants, suppliers and distributors. But the plot to infiltrate the cartel’s communications was the first time prosecutors disclosed that they also employed high-tech cloak-and-dagger methods.

The calls themselves were devastating.

In a series of calls from April 2011, Guzmán discouraged one of his enforcers, Orso Iván Gastélum Cruz, from fighting the Mexican police. “Don’t be chasing cops,” Guzmán scolded him. “They’re the ones who help.”

Minutes later, when Cruz, known as Cholo Ivan, complained that the officers should respect him and “behave,” Guzmán tried to soothe him. “You already beat them up once,” he said. “They should listen now.”

“Take it easy with the police,” Guzmán counseled.

“Well,” Cruz answered, “you taught us to be like a wolf.”

In another set of calls, Guzmán discussed sending a cartel operative nicknamed Gato to bribe a new commander from the federal police.

“Is he receiving the monthly payment?” the kingpin asked.

“Yes,” said Gato, “he’s receiving the monthly payment.”

Then, in an astonishing moment, Gato handed the phone to the commander himself.

In the recording, Guzmán told the man that Gato was from “the company” and asked the commander to “take care of him.”

“Whatever we can do for you, you can count on it,” Guzmán said.

The commander responded: “You have a friend here.”

The jury has already heard some of the intercepted calls — albeit without knowing where they came from or how they were recorded. Last month, prosecutors played a call in which Guzmán was heard negotiating a 6-ton cocaine deal with a representative from a left-wing Colombian guerrilla group. In the recording, Guzmán haggled over pricing and insisted on dispatching a “technician” to inspect the product’s quality before sending the guerrillas their initial payment of $50,000.

One of Guzmán’s Colombian suppliers, Jorge Cifuentes, who introduced the kingpin to the IT expert, testified last month that Rodriguez had promised to arrange secure communications for what amounted to the entire cartel’s leadership. His system operated on VoiP, or Voice over Internet Protocol, Marston said Tuesday, and was accessible only to those within the network. According to Cifuentes, Guzmán was able to sign in through Wi-Fi even from his hideouts in the Sierra Madre mountains.

But FBI agents were able to listen to calls a few days after Guzmán made them, Marston said. From April 2011 to January 2012, US authorities captured a total of 1,500 calls with the help of Dutch officials. Those that were believed to have been placed by Guzmán were authenticated, Marston told the jurors, by comparing the high-pitched, nasal voice on the calls with other recordings of the kingpin, including a video interview he gave to Rolling Stone in October 2015.

Working undercover for nearly two years apparently took a heavy toll on Rodriguez.

Last week, prosecutors filed a motion describing how a witness in the case — likely Rodriguez — had suffered “a nervous breakdown” in 2013 because of “the stress” of working for Guzmán.

There was another reason for his mental collapse, prosecutors noted. After he left Guzmán’s employ, the cartel “attempted to locate” the witness, the prosecutors wrote, suspecting him of having cooperated with US federal agents.

c.2019 New York Times News Service