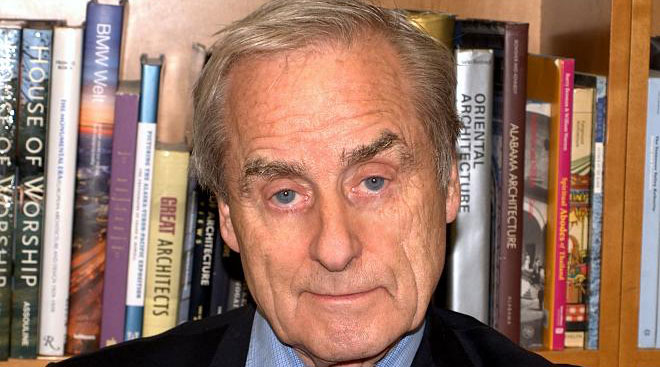

Harold Evans, one of the most influential media figures of his generation and voted “the greatest newspaper editor of all time” by journalists in Britain, has died of heart failure in New York at the age of 92.

Some of Britain’s best known journalists who worked for Evans when he championed investigative journalism as editor of The Sunday Times, London, from 1967 to 1981 paid tribute to the crusading editor who believed facts were sacred and that unbiased and independent reporting was essential in a functioning democracy.

One of them was Ian Jack, the former editor of Granta, who told The Telegraph: “Harry had an almost Victorian belief in the capacity of journalism to improve and enlighten its audience, and went to great lengths to make complex subjects intelligible to the lay reader. Clarity was an obsession. As an editor, he was inspirational, sympathetic and generous. I and many others were lucky to have worked with him and for him. He gave me opportunities — reporting in India was one of them — that changed the direction of my life.”

Assessing what made Evans “an editor’s editor”, Alan Rusbridger, a former editor of The Guardian, said: “He could do it all. Write like a dream; design with impact; edit with flair; dash off the perfect headline; crop a picture…. There was no one who knew more about the craft of journalism, nor anyone to match his passion for communicating that craft — documented in numerous textbooks that were, in turn, studied by generations of would-be journalists.

“What was the one immutable rule of journalism, I asked him in 2010? ‘Things are not what they seem on the surface. Dig deeper, dig deeper, dig deeper’.”

Rusbridger added: “Harry knew there was no point in publishing stories if you didn’t defend them. Though often thin-skinned, he possessed that useful piece of editorial equipment: a backbone.”

The campaign for which Evans is best remembered is exposing the “Thalidomide scandal”, launched in 1972, involving Distillers, a company whose drug prescribed to pregnant women to control morning sickness caused thousands of babies in Britain and across the world to be born with missing limbs, deformed hearts, blindness and other problems.

Along the way were months investigating the life and treachery of the British spy Kim Philby, and exhaustive reporting of what actually happened in Derry on Bloody Sunday in 1972 when 14 demonstrators were shot dead by the British army.

Evans forged his reputation as editor of the Northern Echo in Darlington in the 1960s, where his campaigns resulted in a national screening programme for cervical cancer and a posthumous pardon for Timothy Evans, wrongly hanged for murder in 1950.

Stephen Grey of Reuters, where Evans was editor-at-large, wrote in a tribute: “Evans liked to quote his famous 19th Century predecessor at the Northern Echo regional paper, William Stead, who on appointment declared: ‘What a glorious opportunity of attacking the devil, isn’t it?’”

His fortunes changed when Rupert Murdoch bought The Sunday Times and The Times after a strike by print workers had closed the papers for a year. Evans was moved to the editorship of The Times but quit after a few months.

About his relationship with Murdoch, Evans said: “My principal difficulty with Murdoch was my refusal to turn the paper into an organ of Thatcherism. That is what The Times became.”

He wrote about his experience in his book, Good Times, Bad Times and concluded: “Ultimately, all stands or falls on the values and judgement of the proprietor. At its highest levels, a great newspaper is not simply a personal possession but a public trust.”

In 1984, he and his second wife, Tina Brown, made a new life for themselves in America. While she edited Vanity Fair and The New Yorker, he became the founding editor of Conde Nast Traveller magazine and later president of the publishing giant, Random House.

The couple became leading socialites on the New York scene — their legendary parties were attended by the great and the good.

Pulitzer-winning journalist Robert D. McFadden wrote in The New York Times: “At a party or a breakfast, Mr. Evans conveyed a world-weary charm, talking in cultured tones of books and newspaper adventures. Wiry at 5-foot-7, he could appear slightly rumpled from all the travel. Under flyaway hair, his expression was typically thoughtful, a face out of Fellini: gaunt, intense, lined with a lifetime of editorial decisions.”

McFadden recalled that Evans feared for the future of newspapers and what impact their decline might have on the democratic institutions.

Evans had said in 2009: “The kind of investigative journalism, which I think is the absolute essence, is in danger and, in fact, in many places has vanished. We have to have this searchlight to know what the hell is going on. So when newspapers or TV neglect reporting, so you get chunks of opinion without any factual basis whatsoever, we’re all going to suffer for it.”