Shortly before midday on Friday, Japan marked the 100th anniversary of the most destructive earthquake in the nation's modern history with solemn reminders that the next "big one" could strike the congested capital, Tokyo, at any moment.

And while as many as 142,000 people died in the Great Kanto Earthquake and the fires that tore through Tokyo and Yokohama, experts have warned that the Japanese public is largely unprepared for another natural disaster that is simply inevitable.

Indeed, seismologists put the likelihood of another major quake beneath the Kanto region of Tokyo and the surrounding prefectures at 70% in the next 30 years.

Today, Kanto is home to about 43.3 million people and is the heartbeat of the Japanese economy. In contrast, the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami struck the far more sparsely populated northeastern part of the country, yet still left around 20,000 dead and an enormous and costly recovery project in its wake.

The 1923 megathrust tremor struck with an estimated 7.9 magnitude and just 23 kilometers (14.3 miles) beneath the surface. Survivors' accounts indicated the shaking lasted up to 10 minutes, with landslides and a tsunami of up to 12 meters (40 feet) striking long stretches of coastline to the south of the capital. There were dozens of aftershocks over the following days.

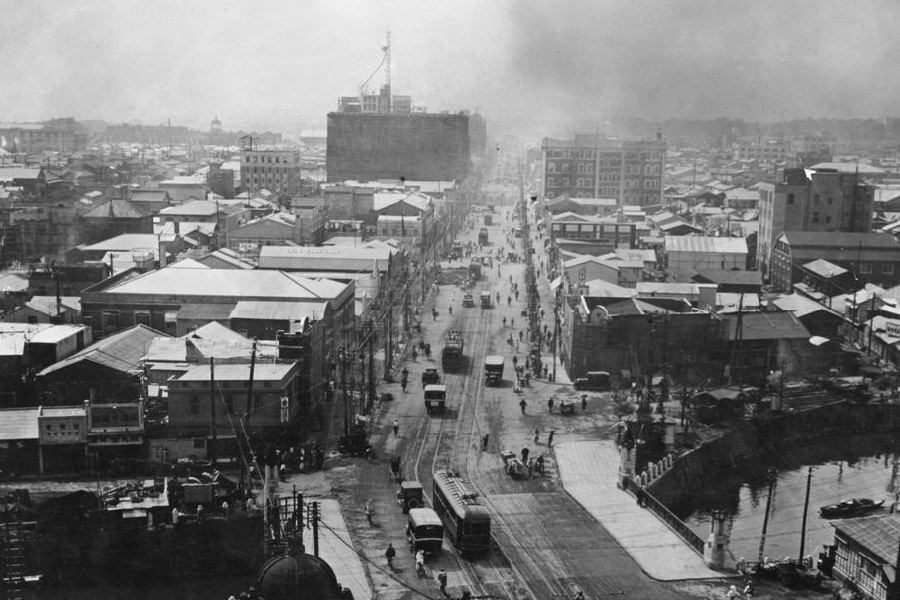

As many as 142,000 people died in the Great Kanto Earthquake and the ensuing fires that tore through Tokyo and Yokohama Deutsche Welle

Many of the deaths were attributed to fires that broke out in the congested back streets of Tokyo and Yokohama, where most houses were still made of wood. There are stories of people being caught in vortexes of fire when their feet became stuck in the melting tarmac of roads.

September 1 was designated as Disaster Prevention Day in 1960, and today local governments carry out disaster drills involving the evacuation of buildings as well as exercises by volunteer firefighters and emergency medical teams.

Schools across the country also conduct emergency drills, along with many private companies.

Yet, despite the scale of the disaster — and a vivid reminder of the power that earthquakes can unleash just 12 years ago — many Japanese remain indifferent about the danger they face.

Takako Tomura, a housewife from Yokohama, isn't worried.

"We have some bottled water stored away and I try to keep some tins of food and others that can keep for a long time, but then I am too busy to go to the shop and I use some of the emergency stocks," she said. "The other problem is that our apartment is not very big, so it is difficult to keep a lot of emergency stocks.

"Obviously, I hope we do not have a big earthquake, but if it happens we will just have to manage the best we can."

Yoshiaki Hisada, a professor who specializes in the study of earthquakes at Kogakuin University in Tokyo, said Japanese cities are now much better prepared to withstand a major natural disaster than they were 100 years ago.

"Certainly, many lessons have been learned. Seismic designs make buildings much safer and the construction regulations make even very tall buildings safe," he told DW.

"The problem is that there are still a lot of older buildings in very densely packed parts of the cities, where fires could easily spread and would be very difficult to extinguish."

Aware of the danger, the Tokyo metropolitan government announced earlier this month that it is stepping up efforts to redevelop all areas in the city that have wooden houses by the 2040s. At present, the city has some 8,600 hectares of old housing that is at greater risk in the event of a major natural disaster.

A study by the city released last year estimated that a magnitude-7.3 tremor directly beneath the city could cause more than 6,000 fatalities and destroy or damage 194,400 buildings.

According to Hisada, the areas that are most at risk are in Arakawa Ward, which has a large number of older properties and is also susceptible to flooding in the event of a tsunami.

"We need to prepare better countermeasures and educate people about the problems they might face," he said.

Residents of one of the most densely populated conurbations on the planet need to know how to turn off gas lines and handle a fire extinguisher, experts stress. They need to know some basic first aid and how to respond when trapped in a tall building when the elevator no longer works, or when doors no longer open because a structure is damaged.

They also need to prepare sufficient supplies of water and basic foodstuffs in their homes for the first few days after a disaster, and be ready to help recovery efforts in their neighborhoods.

Many of the deaths in the 1923 quake were attributed to fires that broke out in the congested back streets of Tokyo and Yokohama Deutsche Welle

"People have to be ready and they will need to help each other, although I do not believe most have the experience or are sufficiently prepared for when an earthquake does happen," said Hisada. "They do not have the food supplies and they do not know how to help an injured person. It is worrying."

Hiromi Iuchi, who works for a company in Tokyo, admits that even with all the coverage of the 100th anniversary of the earthquake she isn't ready.

"In truth, I have not made any preparations," she said. "It's bothersome and perhaps I'm lazy, but my sister takes it all very seriously. She keeps telling our parents to be ready and she has used special fixtures so that the cupboards don't fall on them if there is an earthquake.

"My company has some precautions as well and every year they give us the packages of freeze-dried food that they keep for emergencies just before it expires and they buy new stocks," she said.

"I know people are worried about the next 'big one,' but I was not in Japan at that time so maybe I am not so conscious of how bad things can be."