In South Africa, Nelson Mandela is everywhere. The country’s currency bears his smiling face, at least 32 streets are named after him and nearly two dozen statues in his image watch over a country in flux.

Every year on July 18, his birthday, South Africans celebrate Mandela Day by volunteering for 67 minutes — painting schools, knitting blankets or cleaning up city parks — in honour of the 67 years that Mandela spent serving the country as an anti-apartheid leader, much of it behind bars.

But 10 years after his death, attitudes have changed. The party Mandela led after his release from prison, the African National Congress, is in serious danger of losing its outright majority for the first time since he became president in 1994 in the first free election after the fall of apartheid. Corruption, ineptitude and elitism have tarnished the ANC.

Mandela’s image — which the ANC has plastered across the country — has for some shifted from that of hero to scapegoat.

While Mandela is still lionized around the world, many South Africans, especially young people, believe that he did not do enough to create structural changes that would lift the fortunes of the country’s black majority. White South Africans still hold a disproportionate share of the nation’s land, and earn three and a half times more than black people.

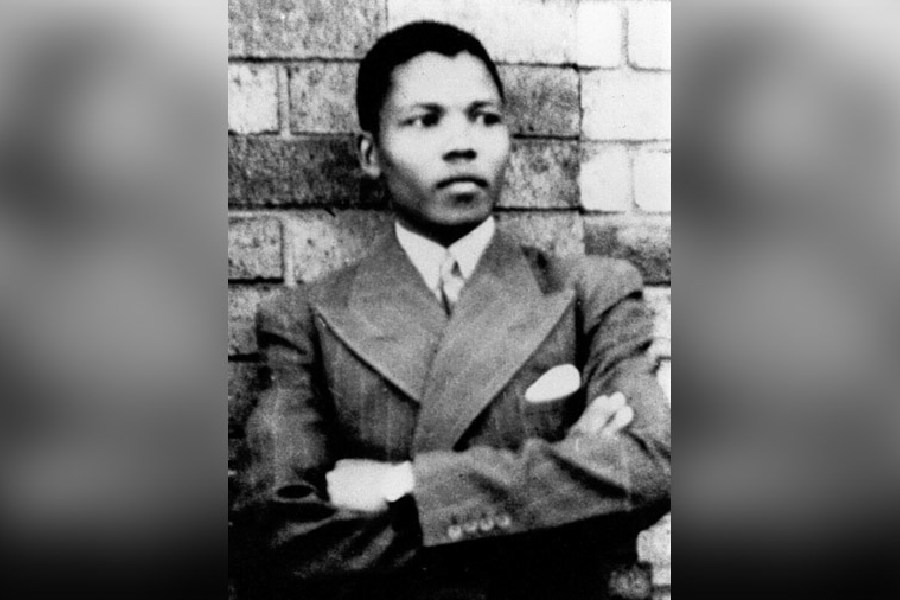

To enter the courthouse in Johannesburg where he works, Ofentse Thebe passes a 20-foot sculpture of a young Mandela as a boxer. He said that he deliberately avoids looking at it, for fear of turning into “a walking ball of rage”.

“I’m not the biggest fan of Mandela,” said Thebe, 22. “There’s a lot of things that could have been negotiated for better when it came to providing freedom for all South Africans in ’94.”

One of his main gripes about the economy is the lack of jobs. The unemployment rate is 46 per cent among South Africans aged 15 to 34. Millions more are underemployed, like Thebe. He studied computer science at the university level, never receiving a degree. The best job he said he could find was selling funeral policies to the staff of the court.

The maze of courtrooms, with marbled pillars and fading signs, was closed on a recent day because of a city-wide water shortage. Days before, the courthouse was shut because the power was out. Blackouts across the country are routine.

Faith in the future is collapsing. Seventy per cent of South Africans said in 2021 that the country is going in the wrong direction, up from 49 per cent in 2010, according to the latest survey published by the country’s Human Sciences Research Council. Only 26 per cent said they trusted the government, a huge decline from 2005 when it was 64 per cent.

In most places, Mandela’s name is associated not with these failures, but with triumph over injustice. There are Mandela statues, streets or squares from Washington to Havana to Beijing to Nanterre, France. This week, the South African government plans to unveil yet another monument, in his ancestral home, Qunu in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province.

But when news of the new Mandela monument came across her social media feed, Onesimo Cengimbo, a 22-year-old researcher and aspiring filmmaker, just rolled her eyes.

“Maybe the old people are still buying it, but we’re not,” Cengimbo said. “It’s actually becoming a little bit annoying that when it comes to elections, they’re not really doing anything different, they’re just showing up Mandela’s face again.”

During the tumultuous transition from apartheid, children of colour were told by their families that Mandela was just one of the many leaders fighting for their freedom. But after he triumphantly emerged from prison in 1990, toured the world and led the country to democracy, he became a singular hero.

On the playground, children jumped rope and sang, “There’s a man with grey hair from far away, his name is Nelson Mandela.” For those who got the chance to be in his presence, it left an indelible mark.

New York Times News Service