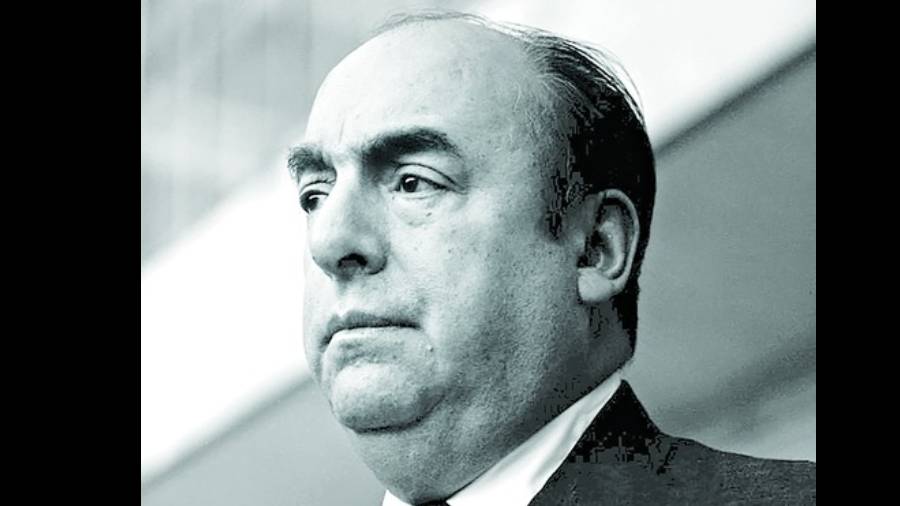

Fifty years on, the true cause of death of the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, in the wake of the country’s 1973 coup d’état, has remained in doubt across the world.

The Nobel laureate was not only one of the world’s most celebrated poets but also one of Chile’s most influential political activists. An outspoken communist, he supported Salvador Allende, Chile’s Leftist President from 1970 to 1973, and worked in his administration.

Neruda’s death in a private clinic just weeks after the coup was determined to be the result of cancer, but the timing and the circumstances have long raised doubts about whether his death was something more nefarious.

On Wednesday, The New York Times reviewed the summary of findings compiled by international forensic experts who had examined Neruda’s exhumed remains and identified bacteria that can be deadly. In a one-page summary of their report, shared with The New York Times, the scientists confirmed that the bacteria was in his body when he died, but said they could not distinguish whether it was a toxic strain of the bacteria nor whether he was injected with it or instead ate contaminated food.

The findings once again leave open the question of whether Neruda was murdered. Neruda was a Chilean lawmaker, diplomat and Nobel laureate poet.

He was regarded as one of Latin America’s greatest poets and was the leading spokesman for Chile’s Leftist movement until the ascendancy of a socialist President, Allende, in 1970. Born July 12, 1904, he grew up in Parral, a small agricultural community in southern Chile.

His mother, a schoolteacher, died shortly after he was born; his father was a railway employee who did not support his literary aspirations. Despite that, Neruda started writing poetry at the age of 13. During his lifetime, Neruda occupied several diplomatic positions in countries including Argentina, Mexico, Spain and France. To the end of his life, he was as engaged in political activism as in poetry. Neruda died in a clinic in Santiago, Chile’s capital, at the age of 69.

His death came less than two weeks after that of his friend and political ally, Allende, who died by suicide to avoid surrendering to the military after his government was toppled in September 1973.

During his time in Barcelona as a diplomat, Neruda’s experience of the Spanish Civil War pushed him into a more engaged political stance. “Since then,” he later wrote, “I have been convinced that it is the poet’s duty to take his stand.”

The diplomat lost his post because of his support of the Spanish Republic, which was dissolved after surrendering to the Nationalists of General Francisco Franco.

He also lobbied to save more than 2,000 refugees displaced by Franco’s dictatorship. Neruda, a lifelong member of the Communist Party, served only one term in office. As a senator, he was critical of the government of President Gabriel González Videla, who ruled Chile from 1946 to 1952, which led Neruda into forced exile for four years.

He returned to his country in 1952, a Left-wing literary figure, to support Allende’s campaign for the presidency, which was unsuccessful then and in another two attempts. In 1970, Neruda was named the Communist candidate for Chile’s presidency until he withdrew in favour of Allende — who was finally elected that year.

Neruda is one of Latin America’s most prominent figures of the 20th century for his poetry and his political activism — calling out US meddling abroad, denouncing the Spanish Civil War and supporting Chile’s Communist Party.

His books have been translated into more than 35 languages. However, Neruda was also a controversial man who neglected his daughter, who was born with hydrocephalus and died at the age of 8, in 1943. And recently, he has been reconsidered in light of a description in his memoir of sexually assaulting a maid.

Neruda was a prolific writer who released more than 50 publications in verse and prose, ranging from romantic poems to exposés of Chilean politicians and reflections on the anguish of a Spain plagued by civil war. His fervent activism for social justice and his extensive body of poems have echoed worldwide, making him an intellectual icon of the 20th century in Latin America.

He published his first book, Crepusculario, or Book of Twilight, in 1923 at 19, and the following year he released Veinte Poemas de Amor y una Canción Desesperada, (20 Poems of Love and a Song of Despair). This collection established him as a major poet and, almost a century later, it is still a best-selling poetry book in the Spanish language.

His travels as a diplomat also influenced his work, as in the two volumes of poems titled Residencia en la Tierra (Residence on Earth). And his connection with communism was clear in his book Canto General (General Song), in which he tells the history of the Americas from a Hispanic perspective.

But his tendency towards communism could have delayed his Nobel Prize, awarded in 1971 for his overall work. According to the prize’s webpage, he produced “a poetry that with the action of an elemental force brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams”.

After Chile’s coup d’état, one of the most violent in Latin America, troops raided Neruda’s properties. The Mexican government offered to fly him and his wife, Matilde Urrutia, out of the country, but he was admitted to the Santa María clinic for prostate cancer.

On the evening of September 23, 1973, the clinic reported that Neruda died of heart failure. Earlier that day, he had called his wife saying he was feeling ill after receiving some form of medication. In 2011, Manuel Araya, Neruda’s driver at the time, publicly claimed that the doctors at the clinic poisoned him by injecting an unknown substance into his stomach, saying Neruda told him this before he died. Although witnesses, including his widow, dismissed the rumors, some challenged the claim that Neruda had died of cancer.

The accusations eventually led to an official inquiry. In 2013, a judge ordered the exhumation of the poet’s remains and for samples to be sent to forensic genetics laboratories. But international and Chilean experts ruled out poisoning in his death, according to the report released seven months later.

The findings said there were no “relevant chemical agents” present that could be related to Neruda’s death and that “no forensic evidence whatsoever” pointed to a cause of death other than prostate cancer.

Yet in 2017, a group of forensic investigators announced that Neruda had not died of cancer — and that they had found traces of a potentially toxic bacteria in one of his molars. The panel handed its findings to the court and was asked to try to determine the origin of the bacteria.

In the final report given to a Chilean judge on Wednesday, those scientists said that other circumstantial evidence supported the theory of murder, including the fact that in 1981, the military dictatorship had poisoned prisoners with bacteria potentially similar to the strain found in Neruda. But they said that without further evidence, they could not determine the cause of Neruda’s death.

New York Times News Service