Shyam Benegal, one of India’s greatest filmmakers who was a prominent name in global cinema and a pioneer of the parallel film movement of the ’70s and ‘80s, passed away on Monday evening. He was 90.

Benegal had been suffering from kidney problems that required dialysis a couple of times a week.

While not in the best of health in recent times, Shyam Babu, as he was known to generations, rarely let anything come in the way of his relationship with cinema. His last film was a project of epic proportions, its runtime of three hours an indication of its scale of storytelling.

Mujib: The Making of a Nation, which chronicled the life and times of Bangladesh’s “Father of the Nation”, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was released last year.

Listing the best Benegal films is a humongous task, given the difficulty of deciding what to leave out more than what to include.

Benegal rose to prominence in the 1970s, his cinema quickly becoming a statement that mirrored the chaotic socio-political environment in a country hit by war, inflation, student and popular protests and, most impactfully, the Emergency that racked India in the middle years of the decade.

Benegal, who “made” his first film at age 12 with a camera given to him by his photographer father, Sridhar B. Benegal, burst on the scene with Ankur in 1974.

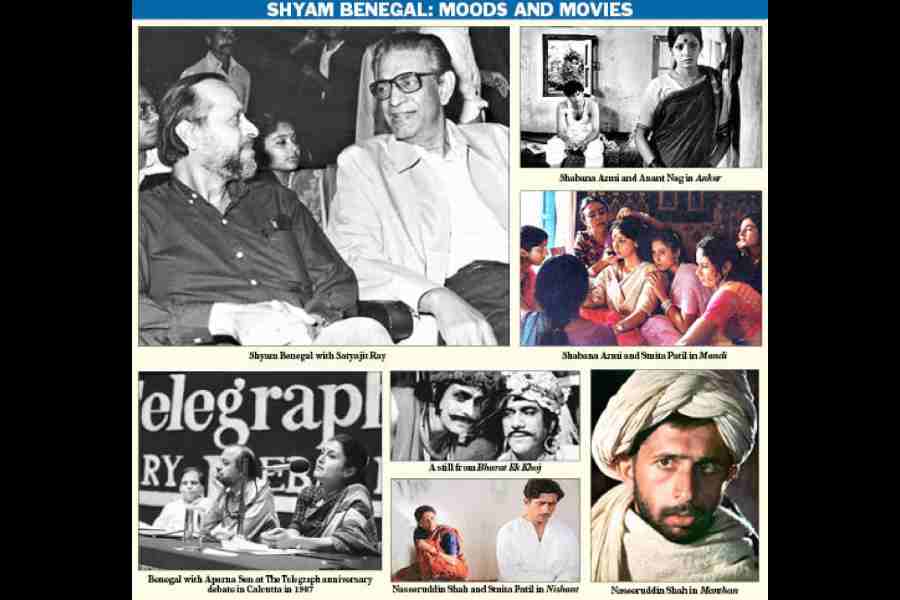

Real, poetic, genuine and disturbing, Ankur also marked the debut of actors Anant Nag and Shabana Azmi. Benegal’s treatment of a prickly subject that spoke about the plight of women and the perils of the caste system immediately established him as a filmmaker with a distinctive voice.

Eschewing the song ‘n’ dance routines and superficial themes of commercial Hindi cinema of the time, Benegal’s stark commentary and nuanced themes and treatment – as in Ankur and the films that followed, particularly Nishant (1975) and Bhumika (1977) — were self-admittedly influenced by Satyajit Ray, with Italian auteur Vittorio De Sica’s impact also showing.

(Benegal made a documentary on Ray that won him one of his many national awards.)

As evidenced very early on in Mandi, Benegal was not afraid to be audacious. In depicting women and their fickle fortunes, he did not shy away from showing things as they were — from incest and prostitution to the undercurrents of lesbianism. But his lens humanised his characters and the situations they found themselves in instead of sensationalising or exploiting them.

Led early by Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil, Benegal made “feminist cinema” long before the term had crept into the dictionary of the woke. His heroines were feisty, never needing a man for approval or anything beyond.

Through the ‘70s and ‘80s, Benegal’s work — always contributing substantially to keeping the New Wave cinema movement of the time robust — ranged from socio-political films focused on the Naxalite movement to those heavy on relationship conflicts, feminism and coming-of-age themes.

Even his men — Naseeruddin Shah, Amol Palekar, Anant Nag were at the forefront — were flesh-and-blood characters, embodying a variety of personalities and emotions.

He could also make larger-than-life cinema and pepper it with famous faces — Junoon (1979) is an example — but Benegal’s cinema never fit into any kind of box.

In his later years, his so-called “Muslim women trilogy” -— Mammo (1994), Sardari Begum (1996) and Zubeidaa (2001) — saw him meld reality with relationship drama, all the while striking a chord with audiences of all generations.

Our Sundays in the ‘80s were made richer by his Bharat Ek Khoj on Doordarshan, its 50-plus episodes skilfully and substantially covering the 5,000-year history of the subcontinent.

Every film of Benegal’s — Manthan to Trikaal, Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose: The Forgotten Hero — was more than just a film. It was a succinct, layered commentary by a filmmaker who had much to say but said it in the most sparing way he could. Their overarching effect remains palpable in the history of Indian cinema.

Benegal turned 90 on December 14, his milestone “birthday party” — he had said in the past that he never celebrated his birthdays apart from cutting a cake with his team — being made special by “his” actors, including Naseeruddin Shah, Kulbhushan Kharbanda, Divya Dutta, Shabana Azmi, Rajit Kapur, Atul Tiwari, and Kunal Kapoor.

Earlier this month, the master filmmaker—the recipient of 18 National Awards and numerous international honours at prestigious film festivals like Berlin and Venice—said he was “working on the scripts of two to three projects.” We hope he writes a good one up there, like he always did.