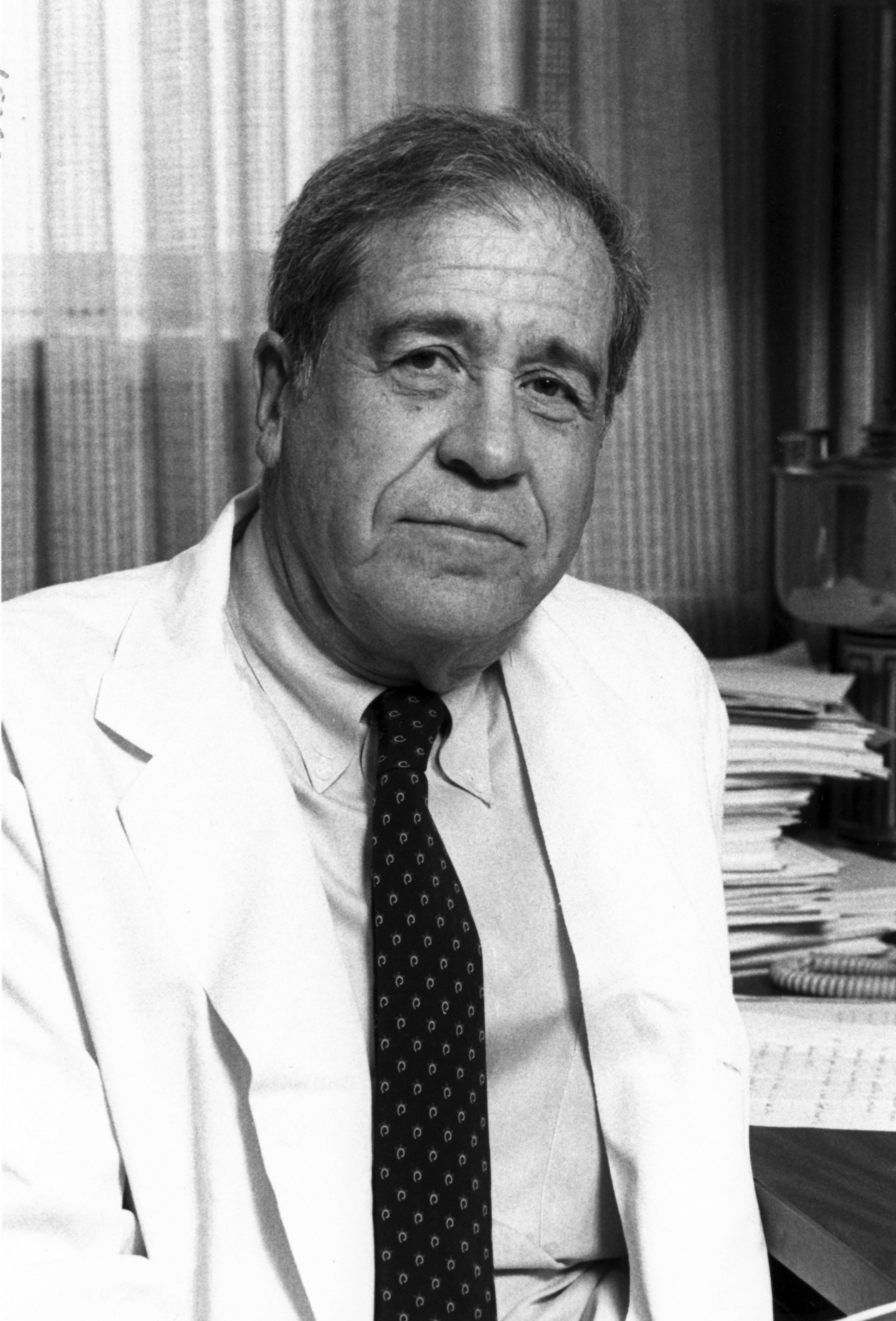

Dr. Bernard Fisher, a University of Pittsburgh surgeon whose research transformed the way breast cancer is treated, bringing an end to the routine use of the debilitating radical mastectomy, died on Wednesday in Pittsburgh. He was 101.

The university announced his death on Saturday.

Fisher’s research, which began in the late 1950s and spanned four decades, showed that early-stage cancers could be treated with simpler surgeries and that treatment with chemotherapy or hormonal drugs could extend patients’ lives. In a radical mastectomy, the breast, the lymph nodes under the armpit, the chest muscle and, in some cases, ribs are removed.

Dogged and ambitious, Fisher prevailed against fierce resistance from academic surgeons, who believed more surgery was always better for patients, while withstanding allegations of scientific misconduct that nearly derailed his career.

Through dozens of clinical trials involving thousands of patients, Fisher brought the scientific process to bear on medical decision-making, which, he said, had too long relied on anecdotes, opinions and untested theories passed down through generations of physicians. “In God we trust,” he once told a reporter. “All others [must] have data.”

“He has to be considered the greatest revolutionary scientist in the history of breast cancer research,” Michael Baum, a professor emeritus at University College London who was trained by Fisher, said in 2002. “He turned the subject around and, as a result, women’s breasts are saved and their lives are saved.”

Fisher’s findings toppled deeply held beliefs about the way breast cancer spread in the body.

Since the late 1890s, surgeons had been taught that breast cancer spread predictably, in ever-widening circles from a single point. The only way to stop the disease, surgeons believed, was to cut out the cancer before it reached the bloodstream and traveled to distant organs and bones.

But the radical surgeries left women scarred and weakened. Without lymph nodes, women’s arms swelled with lymph fluid. Lacking a chest muscle, they had difficulty moving their arms. Many women died from their disease.

Fisher thought that the radical surgeries made no biological sense. Laboratory studies he conducted with his brother Edwin, a pathologist, suggested that cancer spread in erratic, unpredictable ways. Cancer cells reached the bloodstream early in the disease, he said, often before breast cancer was diagnosed. Radical surgeries, he argued, were no better at stopping cancer than limited surgeries, which left a woman’s lymph nodes, chest muscles and ribs intact.

To test his hypothesis, he began a clinical trial, a now-standard methodology that uses statistics to measure the effect of medical interventions. It would take him nearly 10 years to get the data he sought.

Many surgeons, bound to the tradition of radical surgeries, refused to enroll their patients in the trial. “The idea of performing less extensive surgeries was considered, in some institutions, to be the equivalent of malpractice,” Fisher said.

He went to academic medical centers in Canada to get the additional surgeons and patients he needed. A total of 1,765 patients were divided into three groups: one received a radical mastectomy; the second received a simple mastectomy, in which only the breast was cut off; and the third received a simple mastectomy followed by radiation to destroy any cancer cells left behind.

In 1977, Fisher got his results. Women who received radical mastectomies suffered disability and disfigurement but did not live a day longer than women who received simple mastectomies. Among the three groups there was no difference in cancer recurrence, metastasis to distant parts of the body or death rates. By 1979, simple mastectomy had become the standard treatment for breast cancer.

“Surgeons had been taught one thing: radical surgery saves lives,” Dr. Barron Lerner, a New York University professor, wrote in The Atlantic in 2013. “It was Bernard Fisher who changed their minds.”

Fisher was born August 23, 1918, in Pittsburgh to Reuben and Anna (Miller) Fisher. He graduated from Taylor Allerdice High School in 1936 and received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Pittsburgh in 1940 and his medical degree from its School of Medicine in 1943. After completing his postgraduate medical training, he joined the school’s surgical faculty.

His early research focused on liver regeneration in rats. But in 1957, a former mentor invited him to the National Institutes of Health for a meeting about breast cancer.

“I discovered how little information there was related to the biology of breast cancer and what a lack of interest there was in understanding the disease,” Fisher said.

He shifted his research to breast cancer, collaborating with his brother on animal studies to understand how the disease spreads through the body. In 1967, he became chairman of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, a consortium of academic medical centers organised by the National Cancer Institute to run large clinical trials.

Fisher’s group went on to show that the hormone drug tamoxifen, when administered after surgery, could reduce relapses in women with the most common form of breast cancer. The consortium also demonstrated that tamoxifen could reduce the chances that women who were at high risk for breast cancer would develop the disease.

In 1994, however, Fisher was forced to step down as chair of the consortium amid allegations of scientific misconduct in a landmark clinical trial. The trial had found that breast-sparing surgeries known as lumpectomies, followed by radiation, were as effective in early-stage breast cancer as removing the entire breast.

But a researcher at one of the many academic centers that had participated in the study, it was found, had falsified data. Fisher was accused of waiting too long to alert publications that had published it so that it could be corrected.

The falsified data did not affect the study result, but the publicity surrounding the case raised doubts about lumpectomies and made it harder to recruit patients for clinical trials.

The episode led to a congressional subcommittee hearing and an investigation that stretched to nearly three years, but the Office of Research Integrity, the investigative arm of the Department of Health and Human Services, ultimately cleared Fisher of wrongdoing.

“The great tragedy of this, beside my personal harm, is that women in this country thought that the work I did all of these years was not credible,” Fisher said at the time. “They questioned their therapeutic decisions and suffered anxiety needlessly.”

Fisher sued the University of Pittsburgh and the National Cancer Institute, receiving an apology and a $3 million settlement. He continued as scientific director of the consortium.

In 1985 he received the prestigious Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award.

Fisher, who lived in Pittsburgh, is survived by three children, Dr. Beth Fisher, Joseph Fisher and Louisa Rudolph, as well as five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

His wife of 69 years, Shirley Kruman Fisher, died in 2016. A graduate of Penn State University, she had been a researcher at the West Penn Hospital bacteriology laboratory in Pittsburgh and, before they were married, had assisted Fisher in his early experiments at the University of Pittsburgh. His brother Edwin died in 2008.

Colleagues marveled at Fisher’s perseverance as he challenged the prevailing wisdom about how to treat breast cancer.

“He was the most hated surgeon in the history of mankind; his colleagues got to the Cancer Institute and vilified him,” Dr. Vincent DeVita Jr., the former director of the National Cancer Institute, said in the PBS documentary series Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies, based on a book by Siddhartha Mukherjee.

“I sometimes wonder how he survived,” DeVita added. “What struck me was, he was a tough guy.”