Researchers have flagged 82 Indian districts, including three in Bengal, six in Delhi and four in Kerala, with exceptionally high unintended or unwanted pregnancy rates that they attribute to gaps in family planning services, desire for a male child or preference for a small family.

Their study — the first district-level analysis of unintended pregnancies from nationwide data — has revealed what the researchers have called hotspots or geographic clusters of districts where the rates of unwanted pregnancies are significantly higher than the national average.

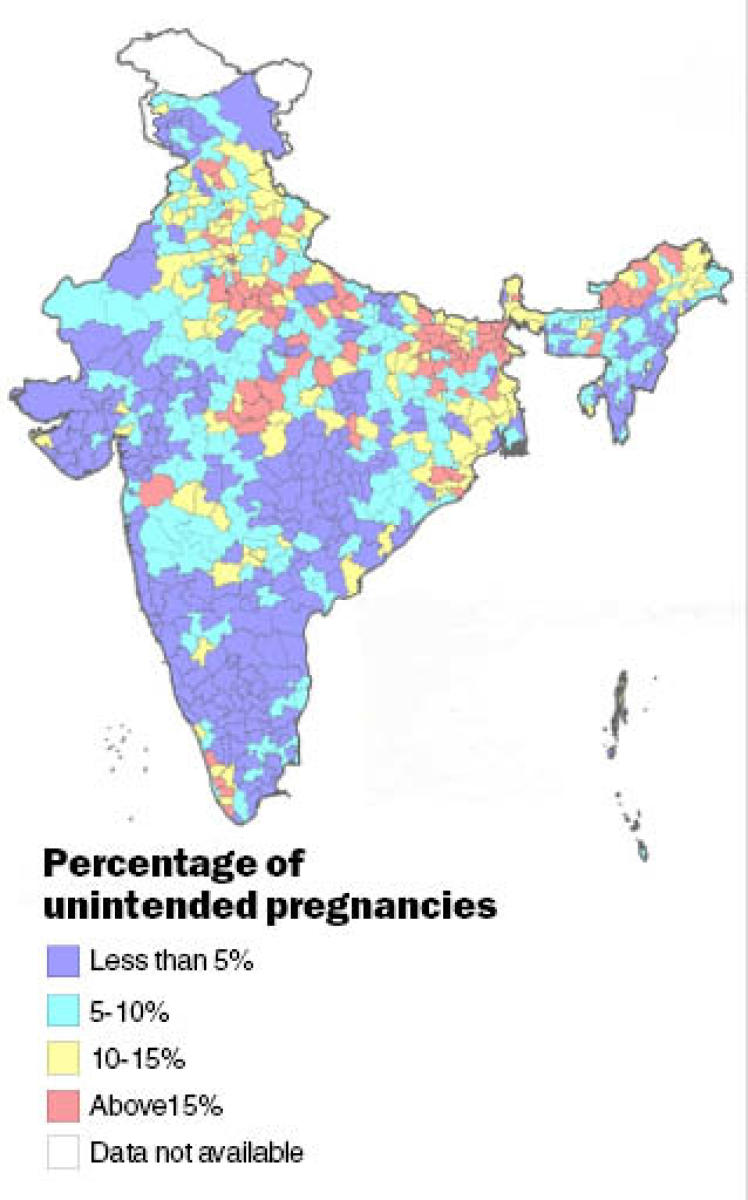

India’s national average is 91 unintended pregnancies per 1,000 pregnancies (9.1 per cent), which is close to three times the average of 34 per 1,000 women in high-income countries. But the national average masks large disparities across the districts.

In the heart of the national capital, New Delhi district has an unintended pregnancy rate of 18.6 per cent, or more than double the national average, the study found.

Birbhum, Malda and North Dinajpur in Bengal and Kottayam, Pathanamthitta, Thiruvananthapuram and Thrissur in Kerala are among 82 districts where unintended pregnancy rates are higher than 15 per cent. In 137 districts, the figure ranges between 10 and 15 per cent.

“Our mapping exercise points to districts that might need special attention to address unintended pregnancies,” Aditya Singh, a demographer and assistant professor of geography at Banaras Hindu University who led the study, told The Telegraph.

“It also throws up questions for future research,” Singh said. For instance, eight of Kerala’s 14 districts have unintended pregnancy rates higher than the national average although Kerala is among the states with the best maternal and child health indicators.

Policymakers could prioritise districts with unusually high unintended pregnancy rates, particularly those where the use of contraceptives is low, Singh and his colleagues say in the study, just published in the journal BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth.

The researchers drew on the Union health ministry’s National Family Health Survey 2019-21, which covered over 219,000 pregnancies from 636,000 sampled households. Around 9.1 per cent of the pregnancies were classified by mothers as unintended, unwanted or wrongly timed.

The study has identified 30 districts in Bihar, 14 in Uttar Pradesh, 8 in Madhya Pradesh, 6 in Delhi, 4 in Haryana, and 3 each in Bengal, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand among the 82 where the unintended pregnancy rates exceed 15 per cent.

“The high rates in Delhi, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh are also unexpected and surprising — like the pattern in Kerala. But the cause may be different in different locations,” said Mahashweta Chakrabarty, a research scholar at BHU and a study co-author.

Districts across Delhi, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh are distinguished by higher per capita income, higher education levels, and enhanced access to healthcare compared with districts in Bihar.

The researchers speculate that the high unintended or unwanted pregnancy rates in the relatively affluent districts of Delhi or Haryana may stem from the longstanding cultural preferences for a male child.

“But it could also be an outcome of a preference for a small family,” Chakrabarty said.

“If a mother wanted a small family, she might have classified the additional child as an unintended pregnancy. The pressure to maintain a small family itself would therefore contribute to (the high count of) unintended pregnancies.”

Many physicians suspect that cultural preferences and social norms are in play in urbanised Delhi, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh.

“Strong and unfortunate son-preference norms persist and likely influence unplanned pregnancies in these regions,” said Prateek Makwana, a consultant embryologist in Jodhpur who was not associated with the BHU study.

“Despite higher income and better access to medical services, such norms could make many couples avoid or discontinue contraception while attempting to have a male child,” Makwana said.

“In Kerala, the high rates might indicate a need for more access to contraception options or better reproductive health education.”