The last, best chance for a peace plan between Israel and the Palestinian authorities came in 2008, when then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert was prepared to give up territory in the West Bank, allow some refugees to reclaim land and even relinquish control of Jerusalem’s Old City to an international committee as part of recognising Palestine as a sovereign state.

And then the potential deal fell apart, for reasons that Olmert still finds difficult to explain. “This was something that would have changed the West Asia,” he said in an interview about his failed talks with the Palestinian Authority’s president, Mahmoud Abbas. “He was not ready to take any risk.”

Abbas, for his part, has said he was not given a proper opportunity to examine the proposed map of the West Bank and asked for more time. Days later, Olmert resigned under a cloud of corruption accusations, and the deal died.

No one in Israel today is thinking about such peace talks, amid fears that a sovereign Palestinian state would find it easier to mount another attack like the one Hamas undertook last October 7, killing 1,200 people and setting off the war in Gaza.

Diplomacy has taken a back seat to military force, in a shift in Israel that reflects years of distrust and failed deals, like the aborted 2008 effort, that have all but cemented the belief among the adversaries that neither side will negotiate in good faith. Officials and experts doubt those attitudes will be reversed any time soon.

Among the democratic nations it is widely agreed that Israel has a right to defend itself from the so-called ring of fire it faces from Iran and its proxy fighters in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria and Yemen that want to destroy Israel.

But last week’s deadly pager and walkie-talkie explosions against Hezbollah operatives in Lebanon — followed by the strike on Friday in Beirut targeting a senior Hezbollah commander that killed at least 45 people, with many still missing — have fueled concerns that with the war in Gaza dragging on, Israel is pivoting away from cease-fire negotiations to free hostages in favour of military action that could touch off a broader regional war.

“The right path, the right steps, is certainly doing the hostage deal, first and foremost, and nothing else,” Efrat Rayten Marom, a left-leaning member of the Israeli Parliament, said in an interview on Wednesday. “We have to do everything in our power to bring them home now.”

Her son, a soldier, is deployed to Israel’s northern border with Lebanon, where more than 60,000 Israeli residents are waiting to return home after leaving last year when Hezbollah began shelling the area to protest the war in Gaza.

“We have to deal with the north because Hezbollah is there,” Rayten Marom said. But “there was a plan, a strategy, to finish the war in the Gaza Strip, first and foremost, and then to deal with the north.”

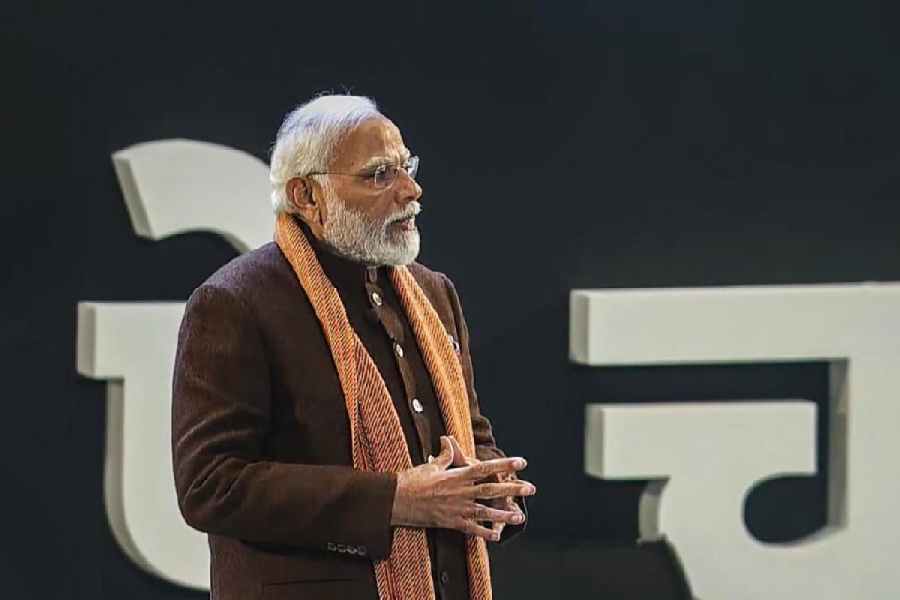

Diplomacy no longer seems to be a priority, she said, under the increasingly combative policies of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel. “I think it reflects this government’s opinion and policy, generally,” Rayten Marom said. “Netanyahu, with his extremist coalition partners, chose and still are choosing this path.”

Netanyahu’s office did not respond to a request for comment this past week. On Wednesday, responding to reports in the Israeli news media, his office said it strongly denied “the claim that he has torpedoed any deal whatsoever due to political considerations.”

Nevertheless, a few hours earlier, Israel’s defense minister, Yoav Gallant, confirmed that “the center of gravity is moving north,” referring to the new focus on Hezbollah.

New York Times News Service