The horror that took place in the early hours of August 21, 2013, is still fresh in the minds of many Syrians a decade later.

"Most of us were awake as it was simply too hot to sleep," recalled Alaa Makhzoumi, now 30. "We were on our rooftop and enjoying the night," she tells DW.

At around 2:30 am, Syria's deadliest chemical attack struck Ghouta, then a mainly opposition-held suburb of the country's capital Damascus.

"When we heard explosions, we thought it was the usual shelling," Makhzoumi said. Her husband, a doctor, immediately left the house to see if someone needed help.

"But then, distressed screams from the streets got louder, and our own breathing got more difficult," she told DW. The family covered their faces with wet tissues.

"We feared it could be a chemical attack, and although we didn't know anything about it, we stayed close to the windows."

Deciding to use wet tissues and not seeking shelter in the basement probably saved their lives.

"Families used to hide from the regular bombing by going down to the basement, but this time, everyone who went down to the basement died," Abd al-Rahman Saifiya, who worked that night as a paramedic in Eastern Ghouta, told DW. "Many died not knowing what kind of weapon they were killed with."

According to various investigations and sources, between 480 and 1,500 people, among them many children, died in their sleep or suffocated elsewhere from the attack.

Hundreds of children died when the chemical attack struck Ghouta on August 21 2013 Deutsche Welle

Plenty of evidence

A United Nations Missions investigation confirmed one month after the attack on Ghouta that sarin, one of the most toxic chemical warfare agents, was used.

"The environmental, chemical and medical samples we have collected provide clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin were used," The UN report said.

Sarin is heavier than air and sinks, which is why so many died while seeking shelter in basements.

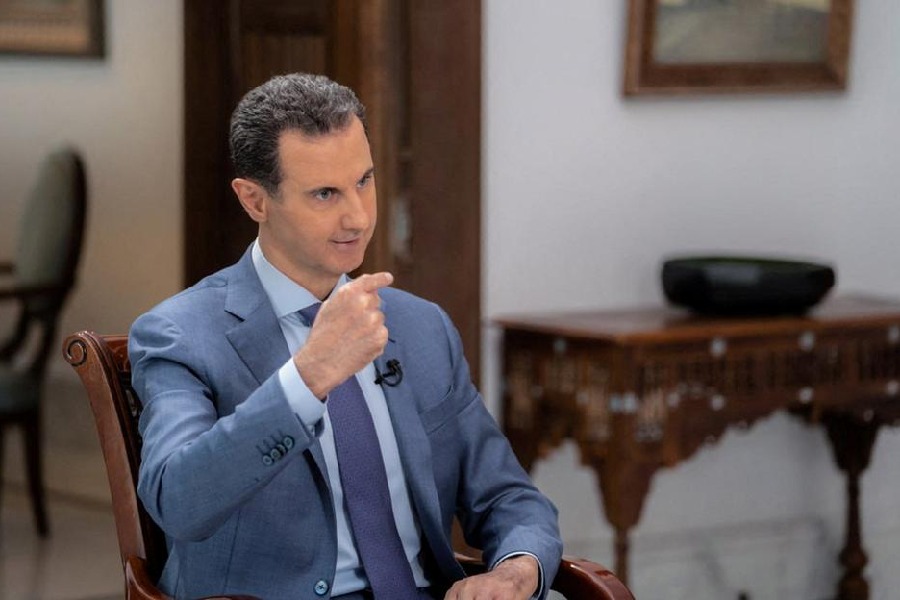

The attack occurred two years into the Syrian civil war, an ongoing conflict between government forces under the regime of President Bashir Assad and other opposition forces.

A comprehensive report by Human Rights Watch (HRW), an international non-governmental organization (NGO), concluded that "the evidence concerning the type of rockets and launchers used in these attacks strongly suggests that these are weapon systems known and documented to be only in possession off, and used by, the Syrian government armed forces."

The HRW report also said Syrian opposition forces did not have the "140mm and 330mm rockets used in the attack or their associated launchers."

Assad rejected any accusation, saying in one of the first reports on the attack by the Syrian news agency SANA, "It would go against elementary logic." Instead, Assad placed the blame on the opposition forces.

The then-Minister of Information Omran al-Zoubi even went as far as saying that "everything that has been said is absurd, primitive, illogical and fabricated," according to SANA.

Only there is no lack of evidence, and several non-governmental organizations have created large databases.

"Documentation from the attack in Ghouta stands out as by far the most documented and most graphic incident that the Syrian Archive has ever investigated," Libby McAvoy, the legal advisor of the Syrian Archive, a project that documents atrocities using open-source material, such as social media content, told DW.

"Almost 300 materials were uploaded basically in real-time, within the first 24 hours, which is about half of the total number of materials we've found that document this attack."

The Syrian Network for Human Rights has also recorded at least 222 chemical attacks in Syria since 2012, this despite a ban on chemical weapons under international law that has been in place since 1925.

But neither Assad nor his Russian allies have changed their stance in the past 10 years. They continue to stick to their version that the opposition was responsible.

Despite immediate help by medical doctors, very few of the children could be saved in the then rebel-held suburb of Damascus Deutsche Welle

Accountability is not a priority

"Assad is playing the waiting game, hoping the world will eventually forget about accountability and pragmatically readmit him into the international community as the legitimate leader of Syria," Lina Khatib, director of the London-based SOAS Middle East Institute, told DW.

"It is crucial that the pursuit of accountability for Assad's brutal actions continues even if the political track of the peace process stalls."

Despite reports and evidence, Syrian President Bashar Assad continues to reject responsibility for the chemical attack in Ghouta Deutsche Welle

For now, it seems, time has indeed played into Assad's hands, Kelly Petillo, Middle East researcher at the European Council on Foreign Relations, or ECFR, told DW.

Despite the alleged war crimes that had temporarily isolated Assad regionally and internationally, the Syrian president has been increasingly re-accepted into the international community and the Arab fold.

"Accountability is not diplomacy," Petillo said, adding that her hopes now lie on an internationally-led political track to a legitimate constituency in Syria. "Pursuing accountability should happen in parallel."

Without accountability, Laila Kiki, the executive director of the US-based NGO The Syria Campaign, a group that supports local activists, fears that there is always a risk that we will see a repeat of these mass atrocities in Syria and elsewhere, she said in a statement ahead of this year's somber 10th anniversary.

For the survivor Alaa Makhzoumi, the past 10 years haven't taken away the trauma she experienced, even though her family eventually made it to Turkey three years after the attack.

"We will never forget the images of the dying children," she said.