Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who after experiencing a sobbing anti-war epiphany on a bathroom floor made the momentous decision in 1971 to disclose a secret history of American lies and deceit in Vietnam, what came to be known as the Pentagon Papers, died Friday at his home in Kensington, California, in the Bay Area. He was 92.

The cause was pancreatic cancer, his wife and children said in a statement.

The disclosure of the Pentagon Papers — 7,000 pages of damning revelations about deceptions by successive presidents who exceeded their authority, bypassed Congress and misled the American people — plunged a nation that was already wounded and divided by the war deeper into angry controversy.

It led to illegal countermeasures by the White House to discredit Ellsberg, halt leaks of government information and attack perceived political enemies, forming a constellation of crimes known as the Watergate scandal, which led to the disgrace and resignation of President Richard Nixon.

The story of Daniel Ellsberg in many ways mirrored the American experience in Vietnam, which began in the 1950s as a struggle to contain communism in Indochina and ended in 1975 with humiliating defeat in a corrosive war that killed more than 58,000 Americans and millions of Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians.

In 1964, Ellsberg was an adviser to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. As American involvement in Vietnam deepened, he went to Saigon in 1965 to evaluate civilian pacification programs.

What he saw began his transformation. It went beyond the failure to win the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese. It was a mounting toll of civilian deaths, tortured prisoners and burned villages, a litany of brutality entered in military field reports as “clear and hold operations.”

To McNamara, Ellsberg forecast a dismal prospect of continued death and destruction, ending perhaps in an American withdrawal and victory for North Vietnam. His reports went nowhere. But McNamara summoned him in 1967, with 35 others, to compile a history of the Vietnam conflict.

In August 1969, he went to a War Resisters League meeting at Haverford College in Pennsylvania, and heard a speaker, Randy Kehler, proudly announce that he was soon going to join his friends in prison for refusing the draft.

Profoundly moved, Ellsberg had reached his breaking point, as he recalled in “The Right Words at the Right Time,” (2002) by Marlo Thomas. “I left the auditorium and found a deserted men’s room,” he said. “I sat on the floor and cried for over an hour, just sobbing. The only time in my life I’ve reacted to something like that.”

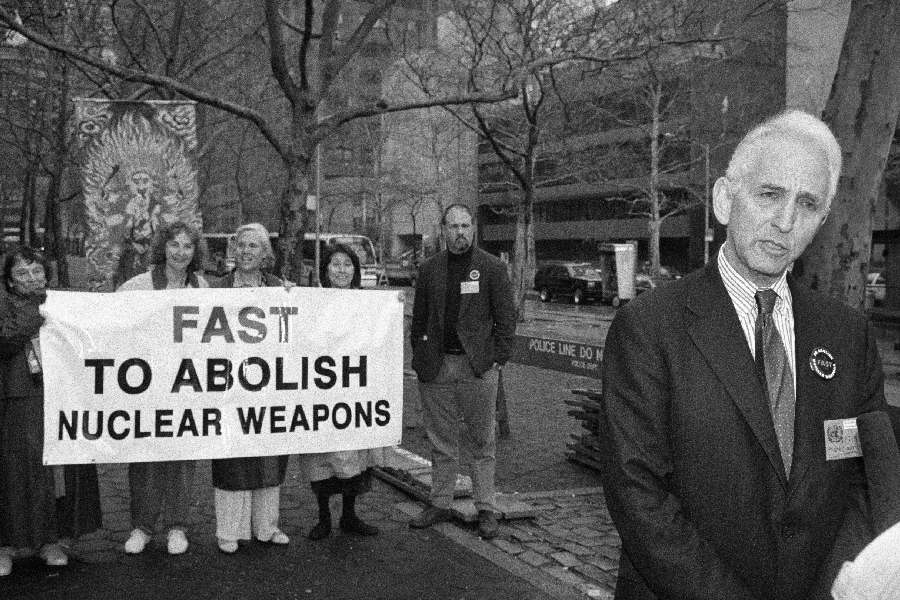

Ellsberg began to oppose the war openly. He wrote letters to newspapers, joined anti-war protests, composed articles and testified at trials of draft resisters. He also photocopied the 47-volume Pentagon study.

Ellsberg approached Neil Sheehan, a veteran New York Times correspondent whom he had met in Vietnam, with the documents. On June 13, 1971, the Times published the first of nine installments of excerpts and analytical articles.

The Pentagon Papers revealed not only that successive presidents had widened the war, but that they had been aware it was not likely to be won. They also disclosed rife cynicism among high officials toward the public and disregard for the enormous casualties of the war. Ellsberg called the conflict “an American war almost from the beginning.”

Daniel Ellsberg was born in Chicago on April 7, 1931, to Harry and Adele (Charsky) Ellsberg. His father, a structural engineer, moved the family in 1937 to Detroit, where the boy grew up. His mother and sister were killed in a car wreck on a Fourth of July outing in 1946.

On a scholarship, he attended Cranbrook, a suburban Detroit prep school, and graduated first in his class. At Harvard, attending on a scholarship, he earned a bachelor’s degree in economics, with high honors, in 1952. He then received a fellowship to study advanced economics at King's College, Cambridge, and returned to Harvard in 1953 for a master’s degree in economics.

In 1951, he married Carol Cummings, the daughter of a retired Marine Corps brigadier general. The couple had two children, Robert and Mary Carroll Ellsberg, before divorcing in the mid-1960s. In 1970, he married Patricia Marx, a toy company heiress and longtime anti-war activist. They had a son, Michael.

He is survived by his wife, children, five grandchildren and one great-granddaughter.

The New York Times News Service