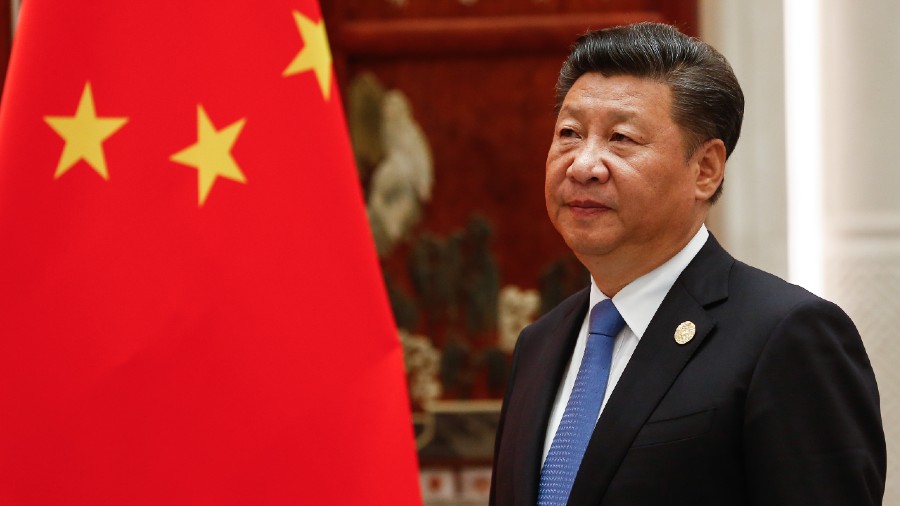

"Without cybersecurity, there is no national security. Without IT applications, there is no modernization" said Xi Jinping, China’s President, at the first meeting of a steering group on cybersecurity in 2014. The true import of these words was brought home earlier this month when China’s cyberspace agency ordered the removal of China’s largest ride-hailing app from app stores just four days after it listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The listing was the largest by a Chinese company since Alibaba’s in 2014.

Didi, which describes itself as the world’s largest mobility technology platform, was among 30 internet companies in China that were ordered to conduct self-inspection for possible violations of China's anti-monopoly rules in April. This was seen as a continuation of the clampdown on technology companies and their high-profile founders that started when Alipay’s Hong Kong listing was cancelled at the last minute last November prompting Jack Ma’s retirement. Since then e-commerce giant Pinduoduo’s Colin Huang, Bytedance’s Zhang Yiming and real estate major Soho Group’s Pan Shiyi and Zhang Xin have also abruptly announced their retirement. It appears that even the patriotic credentials of Lenovo’s founder Liu Chuanzhi whose daughter quit Goldman Sachs to become Didi’s President could not save the company from Beijing’s ire. To drive home its message, the Communist Party has also managed to build public opinion against Didi by alleging that the data it has collected about its customers could fall into the hands of the US government and pose a national security threat to China. As a result, social media posts terming Didi and its management ‘anti-national’ went viral immediately.

Within a short span of nine years Didi had exploited every single competitive advantage that China offers to its technology behemoths such as unfettered freedom to collect and use personal data, lax enforcement of laws, limitless cash from investors and no serious competition. It had swallowed Uber’s China operations along with those of several domestic competitors with the blessings of the government. With a 90 per cent market share, many believed Didi was too big to fail and the word Didi had even become a colloquial substitute for taxi. Although the Cybersecurity and National Intelligence laws were passed back in 2017 just as the US-China trade war broke out, the Anti-Monopoly law was the primary weapon of Beijing’s choice until now to tame technology companies and its high-profile founders. It is perhaps not a coincidence that the new Data Security law which lists transportation data as a sensitive category takes effect in September. The Personal Information Protection Law expected to follow will contain detailed regulations on cross-border data transfers. Together they will provide ample tools to Beijing as it seeks to guard its newfound national treasure – data.

Didi will not be the last company to come under a cybersecurity review. On July 10, the State Internet Information Office issued draft guidelines on "Network Security Review Measures” which will subject every technology company with personal data of more than 1 million users to a cyber security review before they can tap foreign capital markets. With this the strong umbilical cord that connects two of the world’s largest technology ecosystems and venture capital markets will be reduced to a fragile thread. From the opposite direction, the US has also steadily ramped up its scrutiny of Chinese companies on grounds of national security. The fate of investor wealth in more than 240 Chinese companies still listed on American stock exchanges hangs in the balance as both countries accelerate their financial decoupling.

Didi is now facing a plethora of class action suits from investors in the US. Future investors will be wary of backing China’s startups if a US listing to unlock valuation becomes improbable. While it is still too early to call the winners in this tussle, stock exchanges in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore could benefit. Last year’s blockbuster listing of China’s semi-conductor company SMIC on the newly minted STAR exchange offers a clue to Beijing’s vision for its capital markets. The stock rose by a whopping 245 per cent within five days after listing. The message to China’s data-centric companies is clear. Stay closer to home if you want to prosper. An editorial in the Communist Party’s English mouthpiece even spelt it out last week - "No internet giant is allowed to become a super data base that has more personal data about the Chinese people than the country does…”. China has also prepared the foundation for reciprocal actions against foreign companies operating in China to pre-empt discriminatory actions against Chinese companies aboard through its Foreign Investment Law and Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law. Regardless of how the Didi episode unravels it certainly looks like geopolitics has gained a permanent board seat at technology companies.

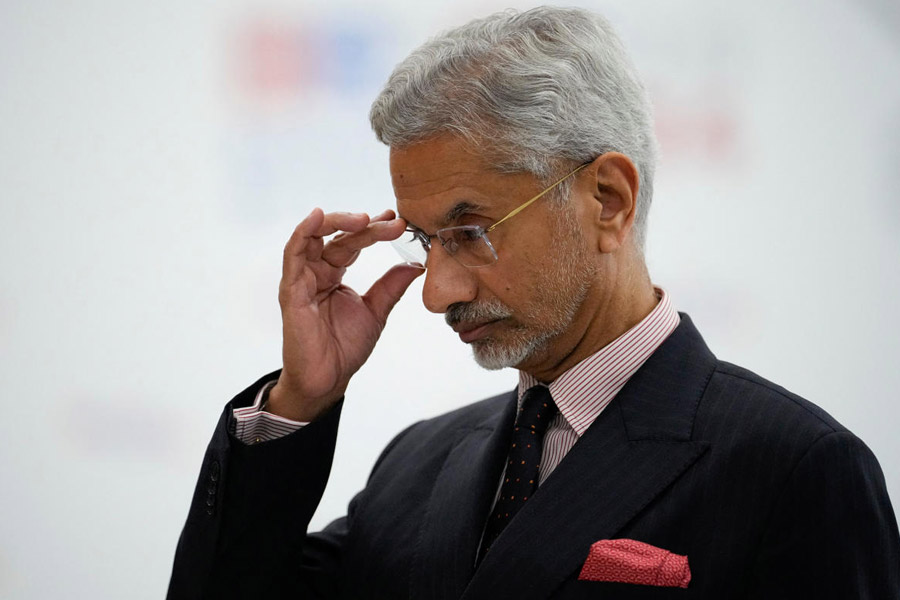

Santosh Pai is a corporate lawyer and honorary fellow at Institute of Chinese Studies.