When the top diplomats of four major Asia-Pacific nations met here on Friday to discuss issues in the region, one had a direct message for the behemoth whose shadow loomed over the talk.

China must “act under the international institutions, standards and laws” to avoid conflict, Yoshimasa Hayashi, foreign minister of Japan, said on a public panel that included his counterparts from the US, India and Australia. That request is one that every official on that stage has made on many occasions.

Although Russia’s war in Ukraine has dominated diplomatic dialogue around the globe this past year, the dilemma of dealing with an increasingly assertive China is ever-present — and for many nations, a thornier problem than relations with Moscow.

They subscribe to the framing that President Joe Biden and his aides have presented: China is the greatest long-term challenge, and the one nation with the power and resources to reshape the American-led order to its advantage.

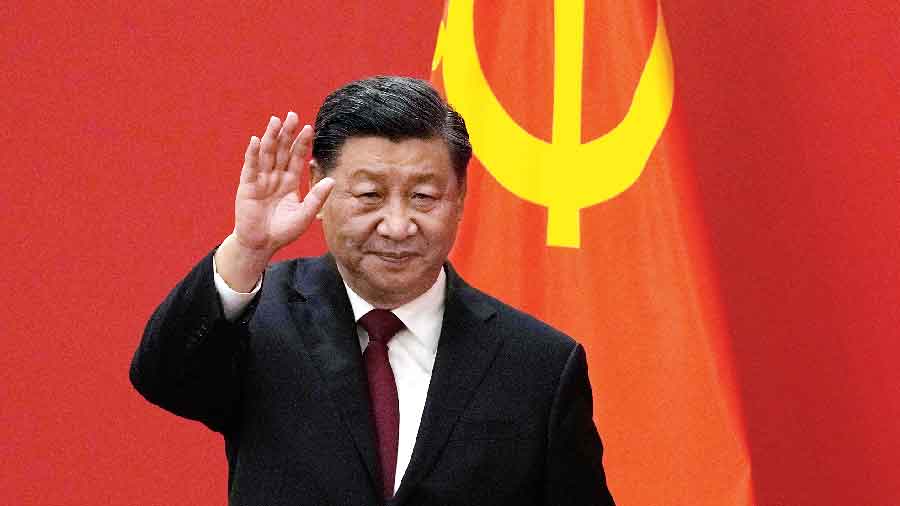

At the heart of this predicament is the fact that the US and its allies maintain deep trade ties with China even as their security concerns and ideological friction with the nation’s leader, Xi Jinping, and the Communist Party of China escalate.

For President Biden and his aides, that tension came into sharp focus in recent weeks after a Chinese spy balloon began drifting over continental United States, and when, in their telling, they came across intelligence that China was considering sending weapons to Russia for its war.

That prospect has prompted American diplomats and those from allies and partners to deliver warnings to Chinese counterparts, including here in New Delhi.

The anxieties over both China’s and Russia’s increasingly discordant roles on the world stage were perhaps wrapped into a lament on Thursday by Prime Minister Narendra Modi that “multilateralism is in crisis today”.

“Global governance has failed in both its mandates” of preventing wars and fostering international cooperation, he said in a video address to a conference of top diplomats from the Group of 20 nations, made up of the world’s major economies, including China and Russia.

The four Asia-Pacific countries represented on the panel one day later at the Raisina Dialogue form the Quad partnership, which was revived in 2017 after many years of dormancy and has gained momentum since, mainly because of shared strategic concerns over China. But in a sign of the delicate balance they are trying to strike in relations with Beijing, the diplomats took pains to stress in their public comments that the Quad is not a security or military organisation.

Hayashi was the sole panellist to mention China, and only after being prompted by the panel’s moderator.

Their joint statement, released after private meetings, did not mention China although many points in it, including the issue of “peace and security in the maritime domain”, are obviously aimedat Chinese policies.

At the earlier Group of 20 conference, the foreign minister of China, Qin Gang, had joined the foreign minister of Russia, Sergey V. Lavrov, in playing the role of spoiler.

Together, they opposed two paragraphs in a proposed consensus communiqué, the first of which directly criticised Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Even though the leaders of the Group of 20 had approved the same two paragraphs in a consensus document at a meeting last year in Bali, Indonesia, China has dug in with Russia to sabotage both this week’s communiqué and a similar one proposed at a G20 finance ministers’ conference in late February in Bangalore.

The second paragraph in the communiqué that they objected to did not mention Russia or Ukraine. It simply said that all the nations agreed to uphold United Nations principles on international humanitarian law, “including the protection of civilians and infrastructure in armed conflicts” and forbidding “the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons”.

Some diplomats privately expressed surprise that China had opposed a reiteration of such basic principles, a move that forced the conference to issue a lower-level chair’s statement.

Qin’s stance seemed to validate concerns that his government was willing to side with Russia in a growing number of diplomatic venues — including at the United Nations Security Council — to undermine policies or actions that the vast majority of nations endorsed.

“Russia and China were the only two countries that made clear that they would not sign on to that text,” Antony J. Blinken, the US secretary of state, said pointedly at a news conference on Thursday night.

He added that he agreed with Modi “that there are real challenges to the multilateral system”. He noted, too, that at the UN Security Council, “we have two countries in particular that tend to block the attempted actions of the council to address some of the most urgent global concerns”.

Chinese officials say they will happily cooperate with countries in the international system, and that it is the US that is fanning the flames of division with its “Cold War mentality”.

After Blinken’s critical remarks, Mao said on Friday that Qin had urged the Group of 20 nations to engage in “real multilateralism” and avoid“ power politics and camps of confrontation”. She added that the G20 was an inappropriate venue for discussing Ukraine, and criticised the Quad partnership as a “closed small circle”. The Biden administration is pushing two allies, Japan and the Netherlands, to also impose further limits on sales of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China.

That subject might have come up when Blinken met his Dutch and Japanese counterparts in New Delhi. Blinken warned China on Thursday night of economic penalties if it went ahead with giving weapons to Russia.

“We have sanctions authorities of various kinds,” he said.

For world leaders, those irrepressible tensions are more evidence that the international system is cleaving into blocs, and that Modi’s urgent plea to diplomats this week was falling on deaf ears: “Focus not on what divides us, but on what unites us.”

New York Times News Service