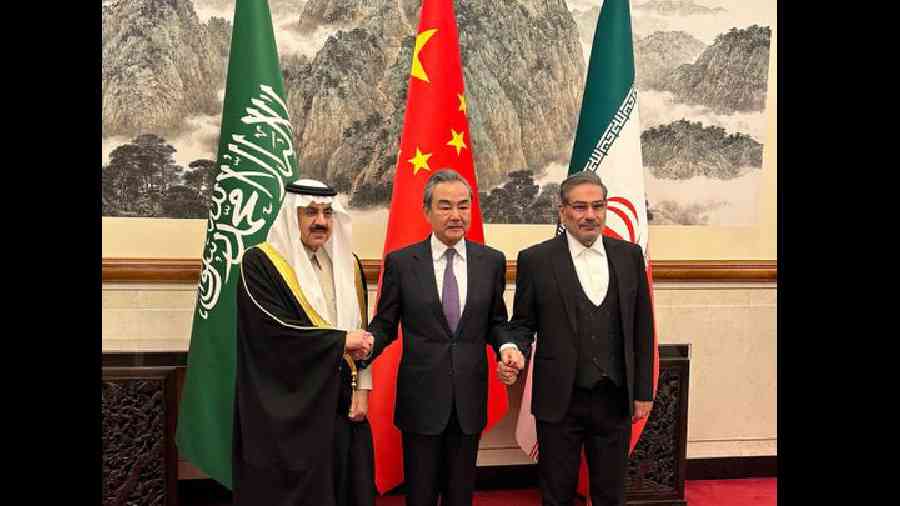

Finally, there is a peace deal of sorts in West Asia. Not between Israel and the Arabs, but between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which have been at each other’s throats for decades. And brokered not by the US but by China.

This is among the topsiest and turviest of developments anyone could have imagined, a shift that left heads spinning in capitals around the globe. Alliances and rivalries that have governed diplomacy for generations have, for the moment at least, been upended.

The Americans, who have been the central actors in West Asia for the past three-quarters of a century, almost always the ones in the room where it happened, now find themselves on the sidelines during a moment of significant change.

The Chinese, who for years played only a secondary role in the region, has suddenly transformed themselves into the new power player. And the Israelis, who have been courting the Saudis against their mutual adversaries in Tehran, now wonder where it leaves them.

“There is no way around it — this is a big deal,” said Amy Hawthorne, deputy director for research at the Project on West Asia Democracy, a nonprofit group in Washington.

“Yes, the US could not have brokered such a deal right now with Iran specifically, since we have no relations. But in a larger sense, China’s prestigious accomplishment vaults it into a new league diplomatically and outshines anything the US has been able to achieve in the region since Biden came to office.”

President Joe Biden’s White House has publicly welcomed the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran and expressed no overt concern about Beijing’s part in bringing the two back together.

Privately, Biden’s aides suggested too much was being made of the breakthrough, scoffing at suggestions that it indicated any erosion in American influence in the region. And it remained unclear, independent analysts said, how far the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran would actually go.

After decades of sometimes violent competition for leadership in West Asia and the broader Islamic world, the decision to reopen embassies that were closed in 2016 represents only a first step.

It does not mean that the Sunnis of Riyadh and the Shias of Tehran have put aside all of their deep and visceral differences.

Indeed, it is conceivable that this new agreement to exchange ambassadors may not even be carried out in the end, given that it was put on a cautious two-month timetable to work out details.

The key to the agreement, according to what the Saudis told the Americans, was a commitment by Iran to stop further attacks on Saudi Arabia and curtail support for militant groups that have targeted the kingdom.

Iran and Saudi Arabia have effectively fought a devastating proxy war in Yemen, where Houthi rebels aligned with Tehran battled Saudi forces for eight years.

A truce negotiated with the support of the United Nations and the Biden administration last year largely halted hostilities.

New York Times News Service