The stunning allegation that India was behind the assassination of a Sikh separatist leader in British Columbia has revived long-simmering tensions within Canada’s Indian diaspora, pitting staunch Hindu nationalists against supporters of the creation of Khalistan.

Last October, in the city of Mississauga in Ontario, the police broke up a fight in which one man was slightly injured after a crowd, carrying Indian and Khalistan flags, became unruly during a Diwali celebration. In March, a Punjabi radio journalist covering a protest of an Indian high commissioner’s visit to Surrey, British Columbia, was attacked by demonstrators.

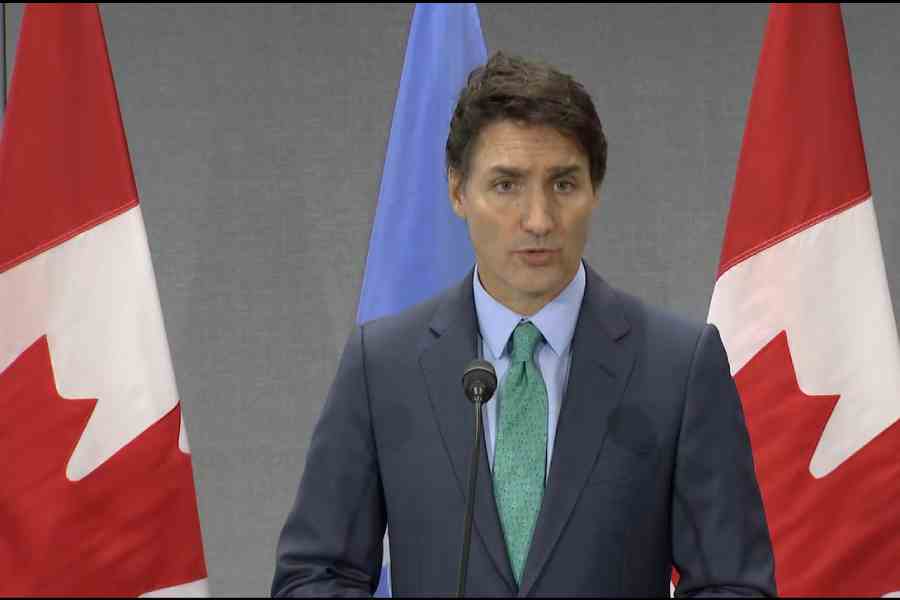

These episodes underscore the challenges that Canada — home to the world’s largest Sikh population outside India — faces following Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s claim on Monday that India was responsible for fatally shooting the Sikh leader, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, in June outside a gurdwara in Surrey, a suburb of Vancouver.

The long-running, tense and sometimes combative relationship between extremists on both sides threatens to spill over into new violence as their members are either empowered or enraged by Trudeau’s allegation.

While Canada has long said that anti-India protests by Sikhs, provided they are not violent, are constitutionally protected free speech, a senior federal government official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive information, said the country recognises that there is a need to find a way to rein in more extreme and inflammatory actions.

Sikhs make up about 2.1 per cent of Canada’s population, roughly 770,000 people, just over half of all people with Indian heritage in the country.

An episode in June prompted an objection from India’s foreign minister, S. Jaishankar. That month, a march in Brampton, Ontario, a city west of Toronto, included a parade float presented by Sikh nationalists that mocked the assassination of Indira Gandhi, who was killed in 1984 by two of her Sikh bodyguards.

Speaking at a news conference several days later in New Delhi, Jaishankar called attention to a video on social media that showed the parade float.

“I think it’s not good for the relationship, and I think it’s not good for Canada,” he said.

Since Nijjar’s killing, tensions between the two communities have intensified. In July, protesters outside the Indian Consulate General, in downtown Toronto, promoted the Khalistan cause with large signs that accused Indian diplomats of being behind Nijjar’s death.

In a statement on the social media site X, formerly known as Twitter, Mélanie Joly, Canada’s foreign minister, called the posters “unacceptable” and said the country takes its duties “regarding the safety of diplomats very seriously”.

Last October, the police intervened after a fight erupted at Diwali celebrations in Mississauga, where a crowd of several hundred was dotted with Khalistan flags on one side and Indian flags on another. The police described the fighting as isolated and did not make any arrests.

Last July, the murder of another Sikh man stoked fears of targeted killings in the Sikh community in Surrey.

Ripudaman Singh Malik, 75, was shot to death in daylight by two men in their 20s whom the police later charged with first-degree murder. Malik was one of the men accused in the 1985 Air India bombing that killed 329 people aboard a flight to New Delhi from Toronto.

He was acquitted in 2005 in a lengthy trial that came after the deaths of many witnesses — some of whom were murdered. Other witnesses were intimidated into not testifying.

Malik’s shooting prompted Balpreet Singh Boparai, a Toronto-based lawyer for the World Sikh Organisation, to approach the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Canada’s spy agency, with his concerns about the safety of Nijjar and other Sikh activists, he said. He said he had also spoken to the local police.

“I had expressed concerns generally about Indian interference in Canada, but also of Sikh activists being targeted,” said Boparai. The statement from Trudeau, he said, validated the community’s fears.

“Sikhs have talked about foreign interference, specifically Indian interference here in Canada, for decades and this is a lived reality for our community,” Boparai said. “But often, this was just written off as conspiracy theories.”

Such stories have swirled around the Sikh community for decades, Mukhbir Singh, a director of the World Sikh Organisation, told reporters during a news conference in Ottawa on Tuesday.

“The younger generation that grew up in Canada, they grew up hearing stories about the persecution, of fear, of speaking out a little too much and you might get on a list or be targeted,” he said. “To see that happening right now in 2023, in Canada, it’s certainly shocking.”

New York Times News Service