On the November day when Cornelio Bonite disappeared, a crocodile was spotted in the water with a human arm clasped in its jaws.

“It was like he was showing off,” said Efren Portades, 67, a watchman in the town of Balabac, a marshy island community in the Philippines near the sea border with Malaysia, who led the search for Bonite, a 33-year-old fisherman.

The month before, another crocodile — or the same one, for all anyone knows — had grabbed 16-year-old Parsi Diaz by the thigh after she jumped into the bay for a swim. She escaped.

The year before that, a 12-year-old girl had been attacked while crossing a river. A few months later, that girl’s uncle was ripped in two.

And more dogs and goats than anyone could count had been snatched from Balabac’s shores.

Some people were ready for revenge.

“I wanted to blow the crocodile up,” said Portades, who intended to use the dynamite that some villagers use to bring up fish to do in the crocodile. “They can arrest me if they want, I will answer to it. I love the people here.”

Saltwater crocodiles once roamed the Philippines, but a century of habitat depletion, dynamite fishing and hunting has left them in just a scattering of places. They are now a protected species.

Balabac at dusk, not far from where a crocodile killed Cornelio Bonite, a fisherman. The New York Times

But their numbers are bouncing back — even as the human settlements near them keep growing.

That means more encounters between people and crocodiles, and more that end badly.

In Balabac, crocodiles have become a fact of life.

Every year since 2015, there has been a fatal attack in the town, forcing authorities to capture another “problem crocodile,” said Jovic Fabello of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development, a government agency in Palawan province, which includes Balabac.

Just last month, a 12-year-old boy in Balabac was attacked but survived.

Making matters worse, villagers in Balabac, and elsewhere, have been poaching mangrove bark, which can be sold illegally to offshore buyers and used to make leather dye. That disrupts crocodiles’ habitats, driving the predators closer to towns and villages.

After Bonite’s body was found half-eaten on a riverbank, Jonathan Montalba, Balabac’s wildlife protection officer, had to remind Portades and other angry villagers that killing a crocodile would have legal consequences.

Worried about the crocodile’s well-being, he sent urgent messages to the Palawan Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Center. Salvador Guion, the head of the crocodile rescue team, assembled five veteran wranglers and left for Balabac the same day.

Their mission? To capture the crocodile.

Nine hours from the nearest airport over half-paved roads and choppy seas, Balabac, a town of about three dozen islands and 40,000 people, still has the natural beauty that was once found across Palawan.

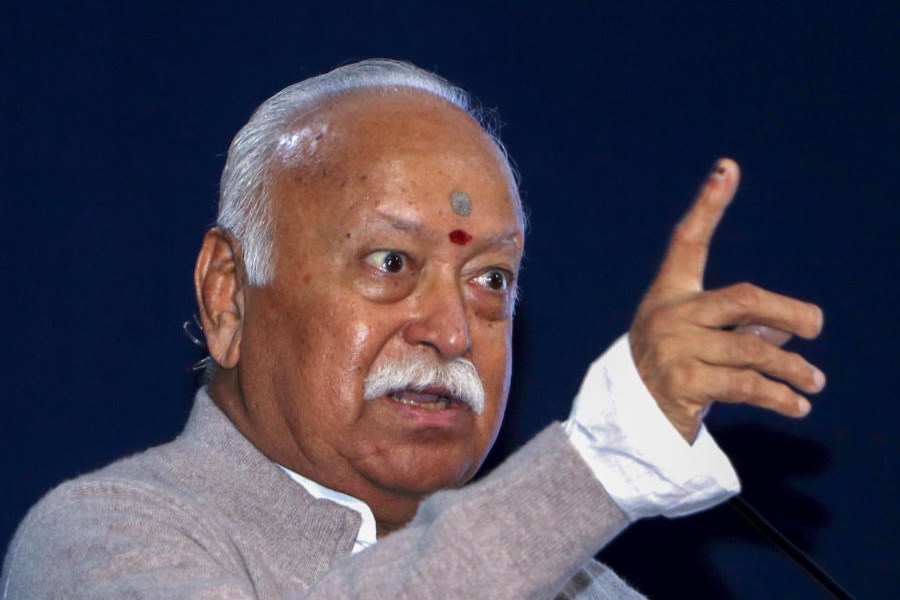

A woman takes a selfie at the Palawan Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Center. The New York Times

Guion said that when he arrived in the town, he thought, “If I were a crocodile, this is where I would want to live.”

Its mangrove forests are thick and streaked with winding estuaries, where fresh water mixes with salt. There are muddy embankments for basking in the sun. Chickens, dogs and goats roam the river banks, and there are plenty of fish to eat.

Apprehending a crocodile was not a task Guion relished. Conservationists would rather leave them in the wild. Part of Guion’s job is teaching people to live alongside the creatures and see them as an essential part of the ecology, not a threat.

In his view, it doesn’t help that buwaya, the Tagalog word for crocodile, is used to describe corrupt politicians and unscrupulous businessmen. Guion considers that a slander against crocodiles.

“They’re being dragged down by politicians, and they have no idea,” he said. “Crocodiles aren’t greedy. They only eat once or twice a week, and even then, just 3 per cent of their body weight at each feeding.”

Guion doesn’t believe the crocodile in Balabac hunted Bonite. He thinks it may have been lying in the mud near his boat and been startled by his movements. “Crocodiles are afraid of people, too,” he said.

A fisherman in Balabac. Crocodiles are a fact of life in the marshy island town. The New York Times

On the morning after their arrival in Balabac, Guion and his team began setting cable snares, strung with slices of goat steak.

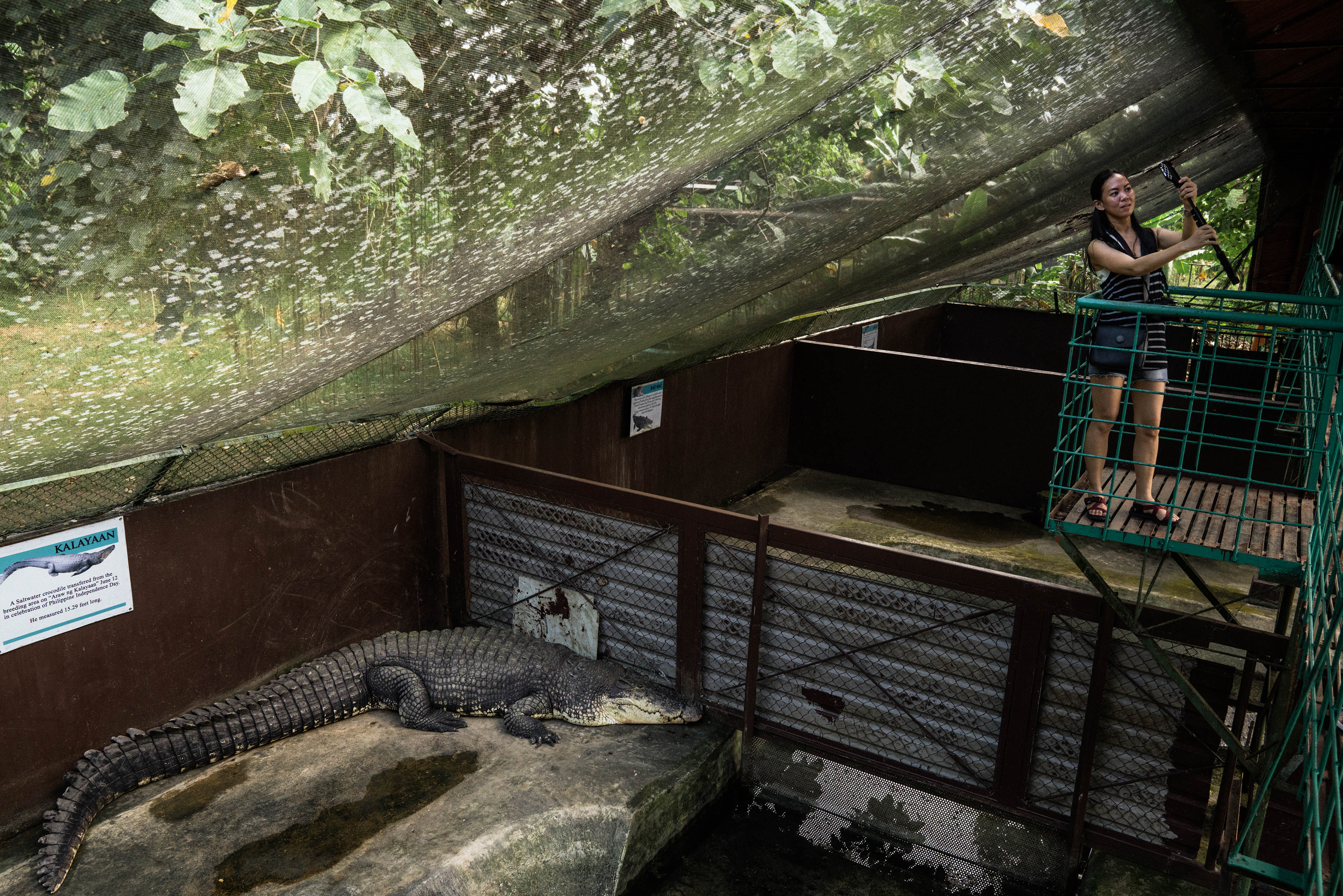

They named their quarry Singko, the Spanish-Filipino word for the number five, after Barangay 5, the neighbourhood where Bonite and Parsi were attacked.

Barangay 5, tellingly, is in the town centre — not the mangrove forests where crocodiles once tended to stay.

Singko was a well-known resident. He had been attracted by the runoff from a pigsty, and he lived on a diet of wandering dogs and chickens. He was accustomed to people; as Guion was setting the traps, Singko loomed in the water 30 feet away.

The next morning, the snares were empty.

Crocodile hunts can go on for weeks, but living near people had made Singko bold, and that undid him in just two days.

In broad daylight, as noisy onlookers watched Guion mend a broken snare, Singko leapt from the water and snapped up the goat steak dangling over the surface.

As he dragged the bait underwater, the snare tightened around his jaw, snapping the poles and tearing the trap apart. The crocodile hunters tugged at the trap’s rope and heaved him onto land.

With the help of dozens of townspeople and a pulley, Guion’s team lifted Singko — 15.7 feet long, 1,050 pounds and estimated to be 50 years old — onto a flatbed truck to be driven to Puerto Princesa, the capital of Palawan province, where he will live out his life in a swampy pen.

Not everyone in Balabac was happy about the capture.

To the Molbog, a Muslim tribe indigenous to the area, crocodiles are sacred, the embodiment of their ancestors. The Molbog word for crocodile, opo, is the same one they use for their grandparents.

“Crocodiles must be respected,” said Dianauya Diaz, 67, a Molbog elder.

“They can try to catch them, but they will not disappear,” Diaz added. “By taking Singko, they planted the seeds of vengeance in his children and grandchildren.”

c.2019 New York Times News Service