Hunter-gatherers on the southeast Asian island of Borneo had performed an amputation more than 25,000 years before Sushruta’s surgical feats in India.

Archaeologists announced on Wednesday their discovery of the skeletal remains of a young adult whose left leg had been surgically amputated with fine precision 31,000 years ago in the eastern part of the island.

Their excavation and study of the skeleton suggests the individual recovered and survived for at least six years after the operation. The find has pushed back the antiquity of surgery by thousands of years, challenging assumptions that surgical practices emerged alongside farming.

“The find destroys long-held narratives… that people who lived in foraging societies were inferior to (people in) agricultural societies and not capable of medico-cultural developments,” India Ella Dilkes-Hall, an archaeologist and study team member at the University of Western Australia, told The Telegraph.

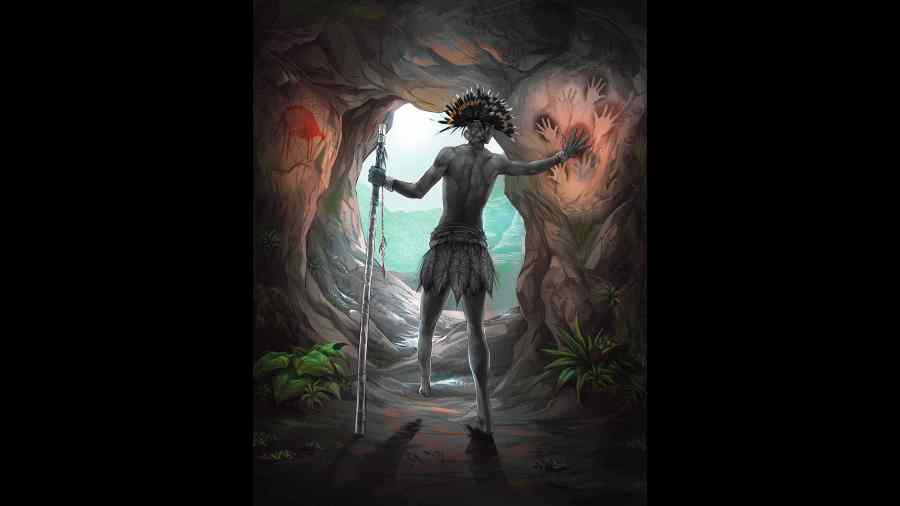

Dilkes-Hall and her colleagues from Australia and Indonesia excavated a large chamber of a limestone cave located on the Sangkulirang-Mangalihat peninsula of East Kalimantan — Indonesian Borneo — and found a young adult’s skeleton intentionally buried with care.

They found the skeleton well preserved with 75 per cent of its bones and all teeth present and intact, but the lower third of the left leg was missing. The clean cuts in the tibia and fibula — the long bones of the leg — and evidence of bone remodelling at those sites point to deliberate amputation.

The researchers described their find in the journal Nature on Wednesday.

The numerous caves and rock shelters in the area abound with archaeological evidence of prehistoric human occupation, including rock art on the walls of the shelters inscribed at least 40,000 years ago. Dating studies on charcoal pieces found at the burial site have suggested the remains are 31,000 years old.

The researchers said an accident or animal attack was unlikely to have caused the loss of the leg because bone injuries from such events show crushing fractures and other features that were not observed in the skeleton.

Features of the left leg suggest that whoever amputated the lower third must have possessed detailed knowledge of limb anatomy, muscles and blood vessels to prevent fatal blood loss and life-threatening post-surgical infections.

The find shows “clear evidence” of deliberate amputation, said Tim Maloney, an archaeologist at Griffith University in Australia and another team member. The evidence also suggests “high levels of community care after the amputation and a probable advanced grasp of antiseptic and antimicrobial technology”, Maloney told this newspaper.

Historians of medicine have long viewed ancient India’s Sushruta, who lived around 600BC, as a pioneer in surgery, citing his legacy, the Sushruta Samhita, a Sanskrit textbook that describes over 300 surgical procedures grouped into several categories — excision, puncturing, exploration, extraction, evacuation and suturing.

But archaeological studies in Europe have turned up evidence of hand amputation in present-day Bulgaria 6,000 years ago, and an arm amputation in present-day France 7,000 years ago.

The scientists were unable to determine the sex of the individual from the skeletal remains in the Borneo cave. But the evidence points to an age between 19 and 20 years at the time of death, implying that the amputation had been performed on a child.

Charlotte Ann Roberts, an archaeologist at Durham University in the UK who was not associated with the excavation in Borneo, said it was “astounding” that the child survived the amputation procedure and lived for several years.

“It raises the question of how bleeding was controlled during and after the operation,” Roberts wrote in a commentary in the same issue of the journal, speculating that plant material such as sphagnum moss could have been used for this.

Dilkes-Hall said the evidence suggested that the people who performed the operation possessed “incredible knowledge around human anatomy and arterial blood flow”.

The discovery has also prompted the researchers to speculate whether the Borneo islanders had figured out ways to exploit botanical resources locally available in the tropical rainforests for pain relief, antiseptic and antimicrobial actions.

The researchers said survival after the loss of a left foot would have been hard in a hunter-gatherer community and the post-amputation survival for six to nine years implied some level of care being provided by others in the community.

The findings suggest that long before modern humans set up farming communities, they possessed an advanced culture that included art and medicine, said archaeologist Melandri Vlok, a team member at the University of Sydney.

It is unknown whether the amputation in Borneo was a rare and isolated event or whether the community had acquired a proficiency in such procedures. But the researchers have inferred that comprehensive knowledge of human anatomy, physiology and surgery may have developed through a trial-and-error process and been handed down the generations even in the absence of written language.