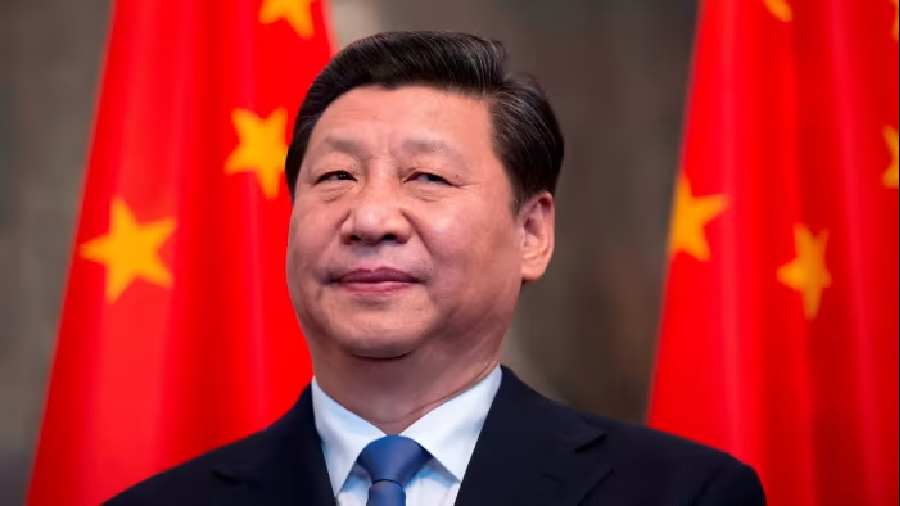

As he heads into an expected third term as president, China’s top leader, Xi Jinping, is signalling that he will take a harder stance against what he perceives as an effort by the US to block China’s rise. And he’s doing so in uncommonly blunt terms. Xi has hailed China’s success as proof that modernisation does not equal westernisation.

He has urged China to strive to develop advanced technologies to reduce its reliance on Western know-how. Then on Monday, he made clear what he regarded as an important threat to China’s growth: the US.

“Western countries led by the United States have implemented all-around containment, encirclement and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented severe challenges to our country’s development,” Xi said in a speech, according to China’s official news agency. In an indication that Xi’s forthright approach signalled a broader shift in Beijing’s rhetoric, China’s new foreign minister on Tuesday reinforced Xi’s message about containment.

Xi’s new directness could play well at home with a nationalist audience but risks raising wariness abroad at a time when Beijing has sought to stabilise ties with the West. It reflects how he is bracing for more confrontation and competition between the world’s two largest economies.

His meeting with President Biden in November had raised hopes that Beijing and Washington might try to arrest the downward spiral in relations. Tensions have since only escalated over American support of Taiwan, the democratically governed island Beijing claims as its territory, as well as US accusations that China operates a fleet of spy balloons, a claim China has denied. The Biden administration has depicted Xi as seeking to reshape the US-led international order to bolster Beijing’s interests. China’s close alignment with Russia, at a time when the West is seeking to isolate Moscow over its war on Ukraine, has intensified concerns about a new type of cold war.

“This is the first time to my knowledge that Xi Jinping has publicly come out and identified the US as taking such actions against China,” said Michael Swaine, a senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “It is, without doubt, a response to the harsh criticisms of China, and of Xi Jinping personally, that Biden and many in the administration have levelled in recent months.”

China’s foreign minister, Qin Gang, the former ambassador to the US, defended Beijing’s right to respond. “The US actually wants China not to fight back when hit or cursed, but this is impossible,” he said at a news conference in Beijing on Tuesday.

Qin also called for the US to take a less confrontational stance towards his country. “If the US doesn’t step on the brakes but continues to speedup, no guardrail can stop the derailment,” he said. China has come under increasing pressure from the US and its allies to use its influence on Russia to stop the Ukraine war. Washington has also publicly accused China of considering sending weapons to Russia for its war.

Qin, the foreign minister, denied the weapons allegations and criticized US weapons sales to Taiwan. He blamed an “invisible hand”— the US, in other words —for escalating the conflict in Ukraine. China “is not a party to the crisis and has not provided weapons to either side of the conflict”, Qin said. “So on what basis is this talk of blame, sanctions and threats against China? This is absolutely unacceptable.”

China’s ambitions have also fuelled pressure and scrutiny from the US on trade and technology. As China has built the world’s largest navy and asserted its claims over Taiwan and the South China Sea, a bipartisan consensus has formed in Washington in favour of reducing American dependence on manufactured goods from China. The tariffs that President Trump imposed on a wide range of Chinese exports to the US are still mostly in place. President Biden has also imposed broad curbs on the export to China of semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

New York Times News Service