No pandemic in documented human history matches the Black Death, the outbreaks of bubonic plague that ravaged Eurasia and wiped out over half of Europe’s population during the mid-14th century. But its origins have remained elusive.

Now, a 13-member team of anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, and geneticists has used inscriptions on medieval tombstones, historical records, and advances in computational genomics to trace the origins of the Black Death to a plague outbreak in 1338-39 in northern Kyrgyzstan.

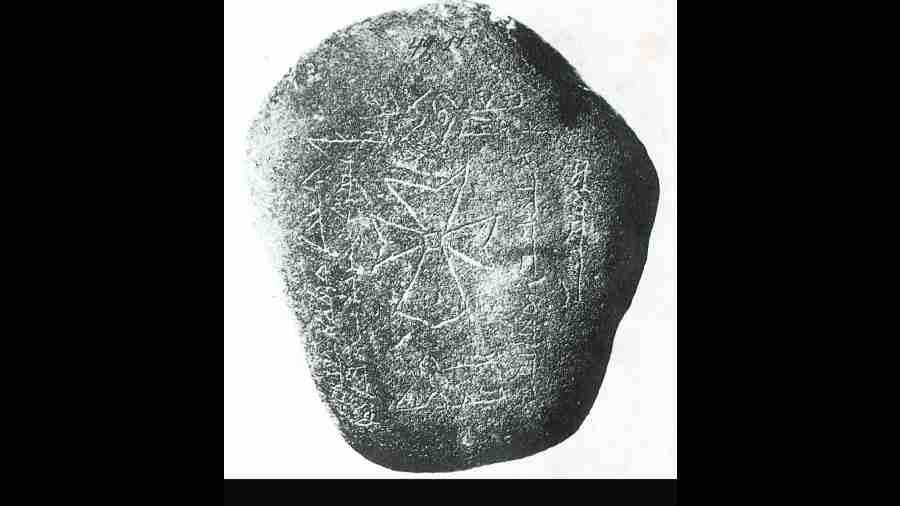

The researchers announced on Wednesday that they have found DNA, or genetic material, of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis in DNA samples extracted from the skeletal remains of three individuals with the year 1338 inscribed on their tombstones near Lake Issyk Kul in Kyrgyzstan.

Their genomics analysis has also suggested that the Yersinia pestis DNA isolated from the three skeletal remains represent the most recent direct ancestor of the plague strains that fuelled the first wave of the pandemic in Europe starting around 1346.

“Our study puts to rest one of the most fascinating questions in history and determines when and where the single most notorious and infamous killer of humans began,” said Philip Slavin, a historian at Stirling University in the UK and team member, in a media release.

The study appeared in the research journal Nature on Wednesday.

The Black Death from 1346 to 1353 was the first wave of the pandemic that over those eight years claimed the lives of an estimated 60 per cent of western Eurasian populations with profound demographic and socio-economic impacts. A second wave followed, lasting nearly 500 years.

Despite years of research on the topic, the geographical source of the plague pandemic has remained unclear although some scholars had proposed that outbreaks around the Black Sea region in 1346 marked the start of the Black Death.

The new study has now traced the Black Death’s origins to Kyrgyzstan and eight years earlier.

The researchers have also discovered closely related strains of Yersinia pestis in modern wild rodent populations in the Tian Shan mountains close to Lake Issyk Kul, indicating that they could have been a possible source of the 1338-39 outbreak.

The plague bacterium survives only in rodent populations across the world. “Today, the rodents living in that region have the closest living relative of the strain also found in the (skeletal) remains,” said Johannes Straus, an evolutionary anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Anthropology, Germany, another team member.

“We’ve found the Black Death’s source strain and we even know its exact date: 1338,” said Maria Spyrou, a scientist at the University of Tubingen, Germany, who’s studying the history of infectious diseases and the study’s lead author.

The researchers said the available tombstone inscriptions, burial artefacts, coin hoards and historical records suggest that the region around Lake Issyk Kul housed communities that relied on trade and maintained connections with several regions across Eurasia.

The researchers speculate that such trade connections may have contributed to the spread of plague to and from the region during the 14th century.