If you imagine, someday it will happen. If you don’t imagine, it will never happen.

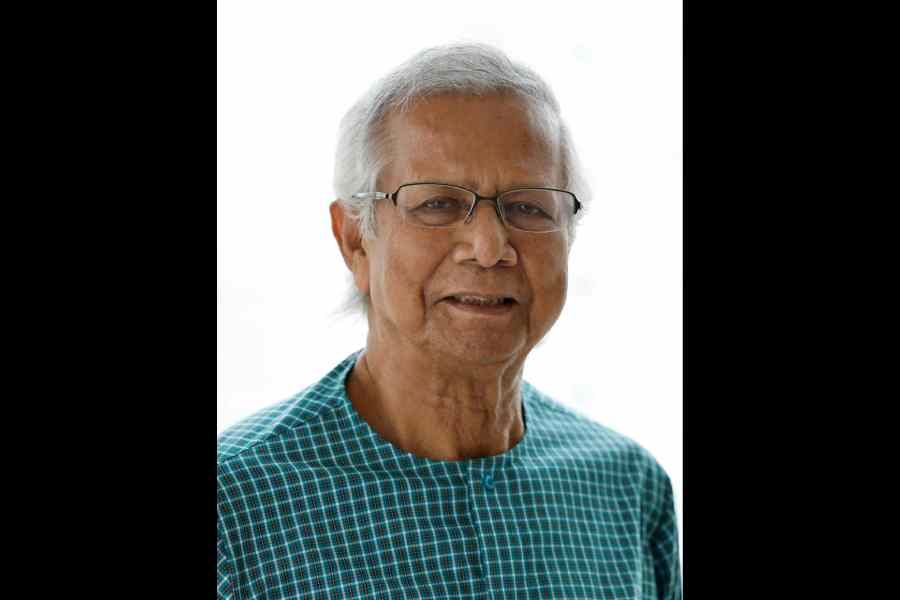

This favourite quotation of Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus — the welcome line at the official website of the Yunus Centre, a think tank for issues related

to social business — has become reality in his own life at a time when Bangladesh is in deep crisis.

The Bangladesh President’s office on Tuesday said Yunus — founder of the Grameen Bank, a micro-credit institution — would head the interim government that will steer the country after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government.

Coordinators of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement, a platform that led the movement against Hasina, had earlier invited Yunus to helm the interim government as chief adviser.

With the formal announcement, Yunus’s 17-year-old dream has come true.

Yunus, known globally as the “Banker of the Poor”, had floated a political platform — Nagorik Shakti or Citizen Power — in 2007 to “create a new politics”.

Under an army-backed caretaker government between 2006 and 2008, Bangladesh was abuzz with the theory of “Minus Two”, which referred to efforts to rid the country of the Awami League’s Sheikh Hasina Wazed and the BNP’s Begum Khaleda Zia.

As Yunus’s 2007 move came at a time when the “Battling Begums” were behind bars and he had the backing of a section of the army, there was speculation that he was ready for the top job.

His tryst with politics, however, didn’t last long. He wound up the platform and hung up his boots as a politician.

His ambition to play a role in Bangladesh’s political amphitheatre, his aides maintain, cost him: his relationship with Hasina soured.

“He was falsely implicated in cases involving labour law violation and financial irregularity. He was even put behind bars. Bangladesh did insult its most famous son,” one of his aides said.

Seventeen summers after he had floated his political platform, the tide has turned in his favour, with the 84-year-old catapulted into the thick of things.

Amid the fast-paced developments on government formation, the first question that comes to mind is why Yunus’s name was proposed.

“They need his brand value as he is known as a progressive and non-communal person. He is known across the globe, be it the US, Europe, Africa or Latin America,” a former Bangladeshi diplomat said.

“I remember, when I presented my credentials as the Bangladesh ambassador to the President of Colombia, he asked, ‘How is my friend Yunus?’”

The ex-diplomat added that Yunus’s background in economics may help restore the Bangladesh economy. Yunus has a PhD in economics from Vanderbilt University in the US, and taught at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro and later at Chittagong University.

The question, however, is whether he can lead an interim government that will be a combination of people from different backgrounds, from hardcore Islamists to secular liberals.

Those backing Yunus think he can restore order to the country using his negotiation skills and international reputation.

“The 1996 parliamentary elections, which the Awami League won, was held under a caretaker government that had Yunus as an adviser,” Shamsher Mobin Chowdhury, former foreign secretary of Bangladesh, said.

“As it was a very close contest and the BNP was trailing by a small margin, they were not allowing the election commission to declare the results. Yunus didn’t waste any time in calling up his friends in the governments of the US and other European countries and also the United Nations.

“Soon, there was pressure on the caretaker government from these countries and the UN, and the result was declared. In these testing times, Yunus’s global reach will be an asset for Bangladesh.”

There are divergent views, too.

A source in Dhaka said Yunus might find it difficult to handle the pulls and pressures of running an interim government where the armed forces, too, would have a lot of say.

“He is a very self-oriented person. Those who have worked with him at Grameen Bank know that very well. He doesn’t have the skills to handle divergent views,” a source who had once worked with Grameen said.

“Hanging out with friends from the West in elite hotels or running a profitable financial institution that charges astronomical rates of interest on loans extended to poor women is different from negotiating with shrewd politicians, army generals and religious leaders. It will not be easy for him as he will not like dealing with the army.”

Sources in the Indian establishment too are wary of Yunus, known as a favourite with the US establishment, amid murmurs in Dhaka that Washington played a role in the regime change.

“But we will have to wait and see how he handles the responsibility,” a source said.