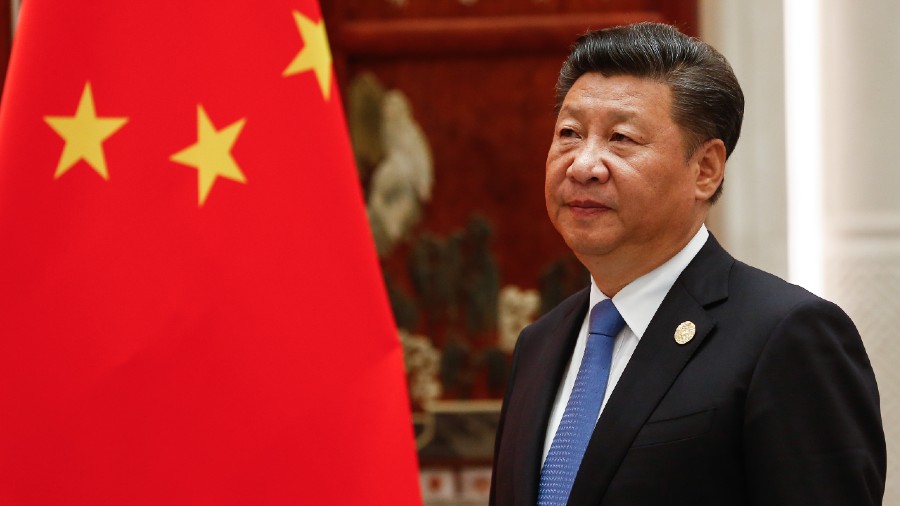

One rising Chinese provincial leader lauded Xi Jinping as the Communist Party’s “greatest guarantee”. The party chief of a big coastal city urged officials to revere Xi’s “noble bearing as a leader and personal charisma”. A top general said Xi had faced down “grave political risks” to achieve the “revolutionary reinvention” of China’s military.

The orchestrated adulation that has carried Xi into 2022 adds to the growing certainty that he will secure another term in power at a Communist Party congress later in the year. In an era of global upheaval and opportunity, scores of senior officials have said, China needs a resolute, powerful central leader — that is, Xi — to ensure its ascent as a superpower.

But one great uncertainty looms over China, and it is of Xi’s own design: Nobody, except maybe a tight-lipped circle of senior officials, knows how long he wants to stay in power, or when and how he will appoint a political heir. Xi seems to like it that way.

“Xi’s political genius is the strategic use of uncertainty; he likes to keep everyone off balance,” said Christopher K. Johnson, the president of the China Strategies Group and a former Central Intelligence Agency analyst of Chinese politics.

At the congress, Xi is highly likely to keep his key post as Communist Party general secretary for five more years, bucking the previous assumption that Chinese leaders were settling into a pattern of decade-long reigns. Chinese legislators abolished a term limit on the presidency in 2018, clearing the way for Xi, 68, to hold onto all his major posts indefinitely: president, party leader and military chairman.

But for how many years? And who would take over after him? The dilemmas of when and how to signal a plan to step away from formal office and confirm an heir could test Xi’s redoubtable political skills.

Keeping everyone guessing could help reinforce loyalty to him, and give him more time to judge potential successors. Yet holding off from designating one could magnify anxiety, even rifts, in China’s elite.

“To pick an heir would make Xi a lame duck to some extent,” Guoguang Wu, a professor at the University of Victoria in Canada who served as an adviser to Zhao Ziyang, the Chinese leader ousted in 1989, wrote by email. “But it would also reduce the pressure Xi has to confront in seeking his third term.”

Confidence, Xi has said, is key to protecting party power, and he wants no surprises to upset a triumphant buildup to the congress.

Setting economic priorities for 2022, China’s leaders repeated “stability” seven times. Beijing is not wavering from its “zero Covid” strategy, while other countries have buckled. This year, too, China’s Winter Olympics, so far untroubled by protest, and planned launch of a space station will bathe Xi in the aura of a statesman.

But the blaze of propaganda will shed few clues about internal deliberations building up to the congress. Secrecy around elite politics is ingrained in Communist Party leaders, and it has deepened under Xi. They see themselves as guarding China’s rise and one-party power in an often hostile world.

Xi’s power games may only come into broad focus when a new leadership files out on the red carpet of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing at the end of the congress, which is likely to convene in November.

Given his desire to keep his options open, Xi is likely to hold off even then from specifically signalling a successor who would be brought into the Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s innermost circle of power, several experts said.

Xi and the premier, Li Keqiang, vaulted into the Standing Committee in 2007, confirming them as the two leaders-in-waiting at the time.

Instead of making a similar move, Xi is more likely to bring a cohort of next-generation officials into the full 25-member Politburo — the tier below the Politburo Standing Committee — creating a reserve bench whose loyalty and mettle would be tested in the years to come.

“The action will probably be in the Politburo,” said Johnson, the former CIA analyst. “Doing anything that would signal a successor now seems unlikely.”

China’s history of botched succession plans stands as a warning to Xi. Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping both had an unhappy record of choosing, then turning on, political heirs.

Xi became top leader in 2012 after a year of lurid strife in ruling circles. He has argued that the fall of the Soviet Union resulted from installing weak, unworthy leaders who betrayed the Communist cause.

“Whether a political party and a country can constantly nurture outstanding leadership talent to a great extent determines whether it rises or falls,” Chen Xi, the party’s head of organisational affairs, wrote late last year in People’s Daily, the party’s newspaper.

Xi has already sought to prevent undercurrents of discontent from converging into opposition before the congress.

New York Times News Service