“From 2,500 tigers to 2,700 tigers is not a big leap. The problem is that there is a shift in baselines. At the turn of the century there were 1,400 tigers in 2006, that’s the new baseline. The shift in baseline creates incorrect perspective of the situation that we have and we celebrate the numbers that is not that impressive for me in terms of tiger conservation,” said Chundawat.

Y.V. Jhala, senior biologist at the Dehradun-based Wildlife Institute of India, who was at the helm of the tiger census, contradicted Chundawat on shifting baselines. “Before 2006, there was no proper methodology to assess the numbers. We have to go by the baseline that we have. Nobody knows how many tigers were there in India at the turn of the previous century or in prehistoric times,” he told Metro over the phone.

If Sankhala’s alarm was the genesis of India’s tiger conservation programme, it was Chundawat’s whistle-blower act that first brought attention to the depleting count of big cats in Panna Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh. Chundawat had been documenting the animal in Madhya Pradesh for more than a decade.

In 2009, he raised the alarm that the tiger population in the area had been completely wiped out. His alarm did not go down well with the authorities. He was accused of irregularities and barred by the forest department from entering the forest he had researched in.

But it eventually prompted action and tigers from other reserves were brought to Panna. Today, there is a thriving population of more than 40 tigers in the reserve. His pioneering 10-year research on the Panna tigers was the subject of a BBC documentary — Tigers of the Emerald Forest. He had also spent years studying the elusive snow leopard in the Himalayas.

The biggest success of the tiger conservation was not in the numbers but keeping the geographical distribution intact, the scientist said. “Wherever tigers were present in any kind of habitat even 50 or 60 or 100 years ago, they are still there,” he said.

But he rued the lack of vision in conservation efforts. “My problem with the census report is not the numbers but the lack of vision shown when the report is out. What are we going to do with these numbers? The problem is that we have only one conservation model that is protected area base, which is very exclusive. We set aside an area and we remove all the threats outside. That is the model. We have not gone ahead. This conservation model has almost no reach outside the protected area.”

Restoring forests way forward

Political pressure to show rising tiger numbers was commonplace even in the 1980s when ‘identifying’ individual tigers by their pug marks allowed officials to keep increasing tiger numbers year after year. Conservation biologists such as Ullas Karanth and Raghu Chundawat got the pug mark monitoring replaced by camera traps and line transects, to estimate both predator and prey population.

Yadvendradev V. Jhala of WII used the M-STRiPES application to bring us closer to actual tiger numbers, but the figures are nothing more than estimations. Controversies have cropped up about the baseline data used and the extrapolation of tiger data from camera traps. But this misses the real issue — habitat loss and ‘islanding’ of tiger populations in natal areas. Kailash Sankhala brought timber extraction, firewood collection and tiger shikar under control. He prioritised anti-poaching foot patrols and soil and moisture conservation works, which provided employment to local people. Water regimes improved and herbivore and tiger populations rose. We need to go ‘Back to the Future’ to resurrect successful Project Tiger strategies of yore instead of counting every last tiger.

Working in unison to connect and restore forests and corridors with local communities becoming the primary beneficiaries of biodiversity renewal is probably the way forward to secure the future of Panthera tigris.

Bittu Sahgal, founder and editor of nature and wildlife conservation magazine Sanctuary Asia

India’s tiger conservation programme should shed its obsession with numbers, a researcher instrumental in reviving the big cat population in a Madhya Pradesh forest asserted in Calcutta on Wednesday.

The National Tiger Conservation Authority’s 2018 tiger census report was released by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on July 29. The report showed that the number of tigers in the wild in India has grown to 2,967, a 33 per cent rise since the last count in 2014, which had recorded 2,226 tigers. The rise in the big cat count triggered euphoria.

But conservation biologist Raghunandan Singh Chundawat had a word of caution. “My sarcastic joke is that if the PM had not been releasing it, then what would have been the figure,” he told the audience at Rotary Sadan on Wednesday.

The researcher, author and whistle-blower was delivering the Kailash Sankhala Memorial Lecture organised by The Junglees, a Calcutta-based NGO.

Sankhala, a conservationist who was the first director of Project Tiger, is famously known as the “Tiger-Man of India”.

“The problem is the celebration about it (the numbers) because the media creates a kind of an environment that it is a big thing that we have achieved. I think it’s something we call conservation amnesia. It’s basically a syndrome of shifting baselines,” said Chundawat.

Chundawat went back to 1969, when Sankhala gave a presentation at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Congress that India hosted, where he put India’s tiger count at around 2,500. The world was shocked and the government banned tiger hunting. A nationwide census that followed put the number at 1,800, prompting then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to start Project Tiger in 1973.

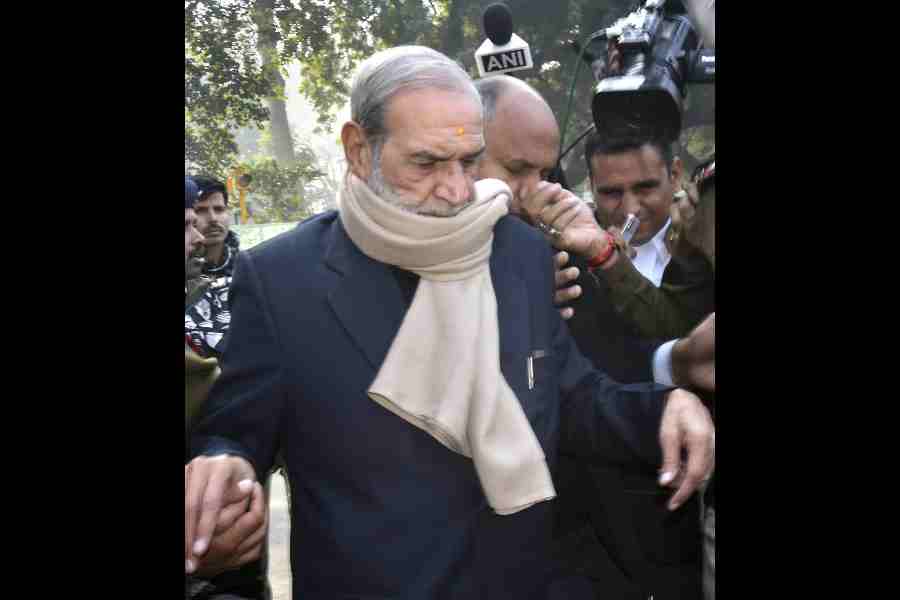

Raghunandan Singh Chundawat and (right) Raja Chatterjee of The Junglees at Rotary Sadan. Picture by Bishwarup Dutta