Four phases of elections are already done in West Bengal, and the past few weeks have been punctuated with reports of crude bombs — confiscations, explosions. Even before the election dates were declared, a peto, or crude bomb, had been lobbed at minister Jakir Hossain while he waiting at the Nimtita railway station in Murshidabad district; he lost a finger to it. One of his companions, who bore the brunt of the bomb, lost an arm and a leg.

A peto is death and destruction wrapped in yards of jute rope. The tying of it is an art and is something of a cottage industry in Bengal. Explosives are wrapped in paper and then the splinters — bits of metal, shards of glass — are added. The whole thing is cocooned in layers of paper and finished off with lashes of sutli dori. “The pressure you apply as you wind the rope around it has to be exactly right — too little and the bomb will not explode on impact, too much and it will burst right in your hands,” says a man who is knowledgeable about such things and who, of course, refuses to be identified.

Peto makers are usually men. Apparently, while making petos, a person has to tie a sari around the waist and dip the free end of it in a bucket of water. If a bomb happens to slide out of the hand — it will either be caught in the sari or slide down it into the bucket of water and get defused. If a peto hits the ground, it explodes.

In rural areas, where petos are more common, they are kept in protective layers of tuush — the discards after rice grain is winnowed — in paper cartons or wooden boxes or even tins, says a man who is long past his days of carrying petos when he went out on “operations”. In urban areas, they are stored amidst crumpled paper.

When embarking on an “operation”, each person carries a single peto because if, god forbid, two petos brush against each other they will explode.

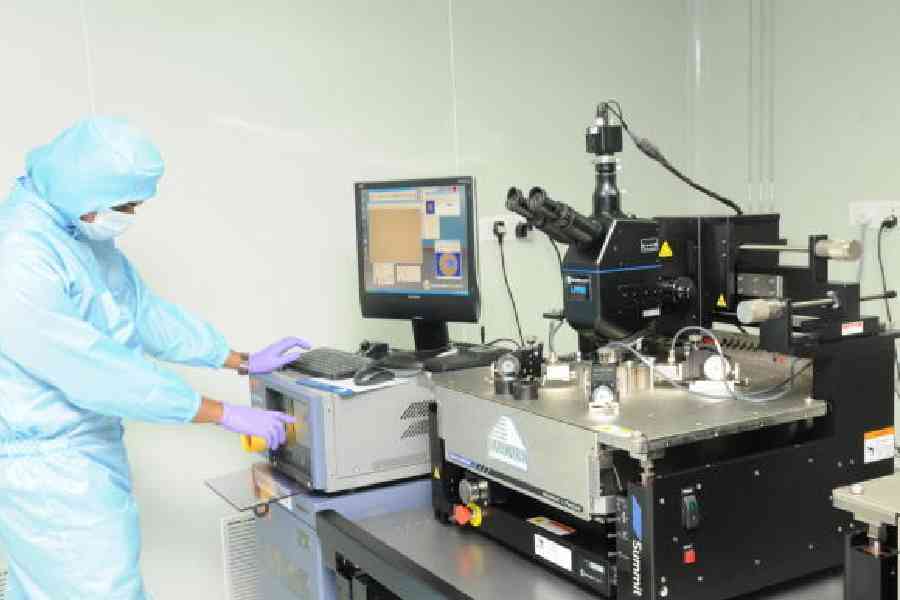

Petos in water Sudip Ghosh

In the period immediately after Independence, there was no such thing as a peto. What was available in 1948-49 were firecrackers called bhuipatka. Made of mom chaal (aluminium powder), gandhak (sulphur) and potash (potassium chloride), those contraptions had to be hurled to the ground to make them explode. Bhui means ground and patka means cracker. The petos of today are possibly based on this prototype.

Violence has been a part of politics in Bengal from pre-Independence times. Post-Independence, in the 50s and 60s too, there was gostidwandho or tiff, shall we say, between groups of different-minded people. When words turned to blows, their weapon of choice was the fist, followed by the lathi and, sometimes, the soda bottle. Such was the destruction it caused that, sometime in the mid-60s, the soda bottle disappeared from shop shelves of Bengal. They are yet to make a comeback.

In 1967, Bengal witnessed the violent peasant revolt in the village of Naxalbari in Siliguri district that gave the Naxalite movement its name. With charismatic leaders like Charu Majumdar and dreams of a better world, it attracted idealistic young minds in hordes.

The movement also believed in revolutionary warfare, and not only in rural areas. Naxals required arms and explosives, which were expensive. But while money was in short supply, brilliance was not. Young Naxals came up with formulae to create bombs from inexpensive and easily available materials. The various formulae were fine-tuned and you had the most effective weapon of destruction — the peto.

The octogenarian who tells this story has perhaps a simplistic view of things but he is adamant that truth lies at the core of his tale. Not everyone involved in the Naxalite movement was there for the ideology, he continues, some were there for the power. And it was these “antisocial” elements, he says, that carried forward the knowhow to make cheap bombs and spread it among their ilk.

The initial petos used scrap iron — nails and sharp little bits of metal — as splinters because they were easily available. The bombs had to be hurled within three feet of the target for maximum effect. They rarely killed outright but always incapacitated the victim and often claimed a body part. But there were occasions when the peto failed to explode.

Like everything else, the peto too has evolved in the last five decades. Its knowhow has spread from political musclemen to petty antisocials and also dacoits. Eventually, some petos were made without splinters. Called dhnuyo peto, these spread more smoke and fear in their wake.

The latest entrant in the house of peto is called ajanta palish. It is supposed to have made its debut during these Assembly elections and apparently has the firepower to flatten people within a 30-metre radius. And that will not be its only avatar, warns the peto maker.

Stay tuned, the tumult across Bengal may have just begun.