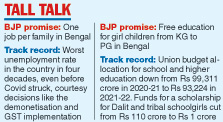

The BJP’s promise of one job per family in its Bengal poll manifesto comes just when the country is witnessing its worst unemployment rate in four decades under the party’s rule, with economists predicting not much improvement in at least the next three years.

The party has also pledged free education for all girl students in Bengal from kindergarten to postgraduate level, a promise that runs counter to the Centre’s falling investment in education.

Economists said much of the job crisis owed to the Narendra Modi government’s policies and decisions, and its track record did not inspire confidence it would be able to meet the Bengal promise — a scepticism echoed by job seekers outside the state.

Ajeet Sonkar from Allahabad, who has been sitting the recruitment exams of the central government and the Uttar Pradesh Subordinate Services Selection Commission (UPSSSC), said he was “awestruck” at the promise made to Bengal.

“The BJP’s past performance suggests it’s an impossible promise,” he said.

Earlier this month, the UPSSSC had cited corruption and cancelled the recruitment process for village development officers (VDOs), three years after holding the exam. Over 9 lakh candidates had taken the test.

“The Centre’s Staff Selection Commission too is delaying the recruitment exam results by up to two years. There are no government jobs,” Sonkar said.

Tribhuvan Singh, a shiksha mitra (contractual teacher without social security) at a government school in Uttar Pradesh is paid a monthly salary of Rs 10,000. He said the state’s nearly 1.72 lakh shiksha mitras had still not been made permanent employees despite the BJP’s 2017 Assembly election manifesto promising to sort out their job issues.

“If the BJP government could not ensure job security for us after we had worked for 10 years, how can it provide jobs to every family in Bengal?” Tribhuvan said.

One of the experts doubtful about the BJP’s promise to Bengal is economist and former JNU professor Santosh Mehrotra, who has edited the book Revising Jobs an Agenda For Growth that sums up the job situation under BJP rule.

The book says that from 2005-06 to 2011-12, India had created 52 million non-agricultural jobs at the rate of 7.5 million a year. But in the following six years, till 2017-18, this dropped to 2.9 million a year.

The unemployment rate rose from 2.2 per cent in 2011-12 to 6.1 per cent in 2017-18, the highest in four decades. The unemployment rate among youths aged 15 to 29 tripled from 6 per cent to 18 per cent over the same period.

Mehrotra accepted that the job situation had suffered during the last couple of years of UPA rule too, but said the persistent decline under Modi’s rule was a result of policy decisions and, therefore, more worrying.

“A policy paralysis after the corruption allegations — some of it still unproven — a global slowdown after 2011, over-lending by the banks were serious problems (that hurt the economy during the UPA’s last years in power),” he said.

He said the poor job creation on Modi’s watch even before Covid struck owed to the weakening of four drivers of the economy from 2014 to 2020, largely because of the demonetisation and the unplanned implementation of the goods and services tax.

The situation worsened further after an unplanned and stringent national-level Covid lockdown was announced without adequate succour for the people, he added.

Mehrotra said the four drivers were:

⚫ Private investment, which was 31 per cent of the GDP when the UPA government ended its term but was 28 per cent in 2019-20.

⚫ The export of merchandise goods, which declined from $315 billion in 2013-14 to $265 billion in 2017-18.

⚫ Household savings, which stood at 24 per cent of the GDP in 2013-14 but had dropped to 17 per cent of the GDP by 2017-18.

⚫ Government investment in the social sector, which remained largely static because of the Centre’s commitment to pet schemes like Swachh Bharat and Mudra Yojana (small loans for small and micro businesses).

“All this affected the GDP and job creation. Even if we get 10 per cent growth in 2021-22, we cannot match the GDP per capita of 2019-20,” Mehrotra said.

“After recovery, GDP growth is unlikely to be more than five per cent beyond 2023. Job creation will therefore remain stressed in the next three years too.”

According to the quarterly data of the Periodic Labour Force Survey, conducted by the National Statistical Office of the central government, the unemployment rate in urban areas had risen from 9.1 per cent in January-March 2020 to 20.8 per cent in April-June amid the lockdown.

Arjun Kumar, director of the Impact and Policy Research Institute, a private think tank, said the demonetisation had shaken the confidence of potential employers and the subsequent economic slowdown had affected job creation.

Labour minister Santosh Gangwar had told the Rajya Sabha on March 24 that the Centre was adopting measures like the Atmanirbhar Bharat Rozgar Yojana under which the government paid the EPFO contributions for two years for private-sector employees who earned salaries below a cut-off.

Gangwar also cited the PM Svanidhi Scheme under which collateral-free loans up to Rs 10,000 are given to street vendors “Employment generation coupled with improving employability is the priority of the government. The government is providing fiscal stimulus of more than Rs 27 lakh crore as part of the Atmanirbhar financial package,” he said.

Education

While the BJP has promised free education for girl students in Bengal, its government has for the first time in years slashed the budget allocation for school and higher education. The Samagra Shiksha scheme, the main vehicle for implementing the Right to Education Act, suffered the highest cut, from Rs 38,750 crore in 2020-21 to Rs 31,050 crore in 2021-22.

This scheme undertakes infrastructure development at government schools and provides uniforms and textbooks to children among several other initiatives.

Several scholarship schemes have undergone funds cuts. One of them is the National Scheme for Incentive to Girl Child for Secondary Education, which covers all girls from the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes who enrol in Class IX at government and aided schools.

A fixed deposit of Rs 3,000 is made for each girl, which they can withdraw along with the interest after reaching 18 years and passing their Class X exam. The allocation for this scholarship plummeted from Rs 110 crore in 2020-21 to Rs 1 crore in 2021-22.

For the National Means-cum-Merit Scholarship Scheme, which provides 1 lakh annual scholarships of Rs 6,000 to Class IX students and continues up to Class XII, the allocation has declined from Rs 373 crore to Rs 350 crore.

The scheme is meant to prevent meritorious students from poor families dropping out after Class VIII, when the midday meal benefit ends.

N. Sai Balaji, a JNU research student said that research scholars were not receiving their fellowship stipends on time.

.“The government does not want intellectual growth. It does not want the poor and the marginalised to advance. So, key education schemes, including scholarship programmes, are facing funds cuts,” Balaji said.