I was born in a house whose walls were carpet-bombed with framed portraits, many of which were of blood relatives I had never heard of, let alone seen. Those impossible not to recognise were not related to us at all: Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel….

My home was not godless but even the original triumvirate of Vishnu-Shiva (Brahma’s pictures are usually kept out) found themselves on a lower pedestal — not because of any discrimination but probably driven by the practical reason that the lamps would be within the reach of the children to be lit at dawn and dusk, every day if possible or occasionally in those days of easy forgiveness.

Still it is undeniable that the Mahatma, Panditji and Sardar commanded at my home a higher profile, so to speak. They were surrounded by a legion of lords, which included Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the scholar and the second President of the Republic, and C. Rajagopalachari, freedom fighter, the first governor of West Bengal and the last governor-general of India.

My life has been inextricably linked to S. Radhakrishnan and Rajaji for the facile and uncomplicated reason that my parents, products of the Nehruvian age, chose to name my brother and me after the two national figures.

I was not particularly — and prophetically — fond of the name. One, even after sandpapering the edges (which made me Rajagopal, not Rajagopalachari), it was a decidedly unfashionable name. Rajiv and Sanjay (or Sanjeev) were the names that were hot then, which derived their firepower from the sons of Indira Gandhi.

In the 20th century, such choices were commonplace. I was told my grandfather wrote to Gandhiji — even though they did not know each other — when my father was born, requesting that the Mahatma suggest a name for the newborn. Gandhiji apparently wrote back saying one of his sons was named Ramdas and it’s a name that he likes. I used the disclaimer “apparently” because I have no evidence, documentary or otherwise, other than the fact that my father was indeed named Ramadas.

Two, I could figure out from the faint shadow of annoyance that crossed faces that it is a curse to be saddled with a name that has more than three or four letters. So, I generally ended up being called “Raj” or “Rajan” in Trivandrum (before it was reborn as Thiruvananthapuram, by when I had left the Kerala capital.)

I suspect my brother Radhakrishan paid a higher price. Introduced, it would be a matter of moments before he would be called “Radha” (good for gender-sensitivity but bad for interpersonal relations with school bullies).

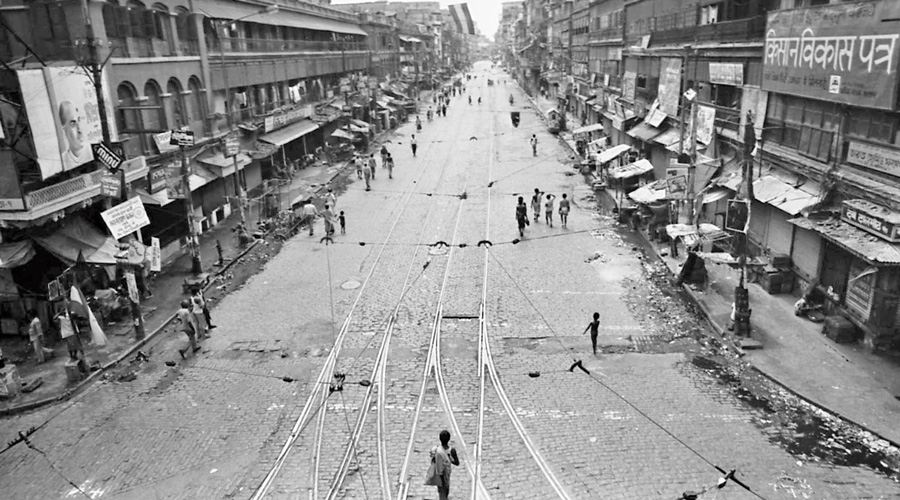

So, although “Raj” and “Rajan” had given me a fair warning early in life, nothing prepared me for the breathtaking metamorphoses my name would undergo once I reached Calcutta to pursue a career in journalism.

Here, “Raja” is the most popular derivative — among the callers, not the called. The shortened name offers opportunities at humour — and sometimes fake humility —– so that gems like “Tumi Raja, ami Praja” can be flashed.

The next day, the name can become “Rajagopala”, “Rajagopale” and then “Rajagopalan”, only to take a longer leap to “Rajagopalachari” with a pause to decide if it is “Rajagopalacharya” or “Rajagopalacharjee (my favourite as it makes me a Bengali without having to wait for the CAA to be implemented.)

Then there is the delayed letdown. Just when I heave a sigh of relief at being addressed as “Rajagopal”, the damper must surely follow with a wedge in between: it is almost always “Raja Gopal”, rarely Rajagopal.

On the phone, some commit the cardinal sin of adding a dramatic twist by making it “Raj Gopal” (the effect of the name “Raj” for heroes in Hindi movies). But, should they come face to face, they rapidly correct themselves and change the call sign to “Raja Gopal”, my girth and the rest of the appearance curing them of any illusions of heroics in me.

Make no mistake. By no means is the name-calling a one-sided match. My atrocious pronunciation mercilessly butchers almost every Bengali name. I plead guilty as charged on this count.

But in the 30 years I have lived in Calcutta, I have mostly not felt hurt or offended at my name being mispronounced or misspelled. In fact, my name has often acted as an ice-breaker or a conversation-starter that led to delightful anecdotes.

One day in Calcutta, I found myself in a roomful of Indians and a bewildered Scot who was struggling to remember names like “Gopalakrishnan”, “Parthasarathi”, “Achyut”, “Damodar”, “Brijesh”, “Keshav”, “Nandlal” and, of course, “Rajagopal”. The problem was solved when an enterprising gentleman told the foreigner: “All these names have the same meaning. You can just call them Krishna1, Krishna2, Krishna3….”

My name has also bailed me out of tricky (and potentially physically perilous) situations. Soon after I reached Calcutta in 1991, Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eeelam (LTTE or Tamil Tigers). I had moved to a PG accommodation, woken up to find the taps dry and, consumed by indignation, had rushed to the landlord to enquire.

A bear of a man, the landlord sized me up and took in my scrawny frame but asked with respect bordering on slight hesitation: “Are you a Tamil Tiger?”

It was then that I realised in my anger, I had marched up to the landlord in a lungi that was tied at half-mast (I did so involuntarily to ensure that I did not trip but forgot for a moment that it is a universal sign for a call to arms).

I also realised that the landlord was genuinely grappling with a snowballing doubt: did he give shelter to a terrorist? I did not mind at all. Neither did I smell any racist or ethnic slur. A manhunt was then going on across the country for possible collaborators who took part in the plot to assassinate Rajiv.

I burst out laughing and he called me “Rajagopalachari” while calming me down with an endearing mix of Hindi and Bengali: “Rajagopalachari, shant ho jaiye, shant ho jaiye, jol aashbe, jol aashbe.”

When I corrected him, the landlord guffawed and told me: “You will always be Rajagopalachari in Bengal.”

Until then, I had little idea of Rajaji’s close association with Bengal. (By coincidence, Gopalkrishna Gandhi, the grandson of Rajaji as well as the Mahatma, would become the governor of Bengal in 2004.)

Eventually, during the evening load-shedding that was fairly common in the early 1990s, my roommates and I would go to his shop downstairs that had a battery-operated lamp. The sight of me would set the landlord down memory lane and he would tell us stories about Nehru and the crowd that packed the Brigade when Indira Gandhi and Bangabandhu appeared together after the Liberation War.

The lungi inadvertently helped me on another occasion, too — and it had nothing to do with my identity. My PG mates and I went for a late-night movie at Globe and were walking through the dark corridors of New Market when some of my friends decided to rib me for wearing a lungi (but at full mast now) to a movie hall and kept calling me “lungi, lungi, lungi….”

We were walking in a procession through the narrow corridors with me at the head. All of a sudden, there was a commotion and several lung-wearing men — workers sleeping in New Market — encircled us, thinking that we were poking fun at them. I convinced the bleary-eyed and fuming men that my friends meant me and I struck a pose with my lungi at half-mast — probably the only occasion I played a hero in my life and it did work. They let us go unharmed.

The last I remember of the landlord is him bellowing from his top floor in Moulali at my wife and I standing below on the road when I took her there to meet him on my off day: “Any issue?”

“Tomorrow night,” I shouted back, assuming that he was referring to the journalistic jargon for the edition of a newspaper.

The landlord let out that “Rajagopalachari” guffaw again. And to my utter embarrassment, I realised that he was asking us if we had any children, choosing the archaic word “issue” (the 12th meaning of the word in Webster’s dictionary is “offspring” or “progeny”) to fire the question.

When the “issue” was born four years later, a child in a Bengali family in our neighbourhood called our daughter Bulbul because her parents could not reach a consensus. Bulbul remains Bulbul’s given name even now, 25 year later.

So, what is the moral of this story? None, none at all. Just a footnote that seeks to redefine or repackage me.

A few weeks ago, it was conveyed to me that an acquaintance (whom I have run into occasionally in the elevator and exchanged pleasantries or smiles with) had told a friend: “Your editor is a Malayali, a communist and a Christian.”

The three “grave charges” were levelled as if they were some sort of crimes against humanity and were responsible for the positions that I took as a journalist.

That I am a Malayali is a fait accompli — I had no role in that decision and occurrence.

That I am a communist is fake news. True communists will be more outraged than anyone else if I, who has enjoyed the privileges that come by birth as well as feudal inheritance and served private capital in my entire working life, pretend to be one of them.

Whether I am a Christian or not — that is none of his business. My faith is my private affair.

Why am I making such a song and dance about a purported stray comment? The conversation came up because the person who apparently charged me with the three “offences” had joined the BJP the same day.

I had once rudely tried to correct a person who had misspelled my name in a letter.

Now I realise the true worth of each such wayward letter, written and uttered not with malice but with the shared confidence that such oversights will be forgiven and forgotten in this great melting pot of a city that has been indescribably kind to me.

“Raja” radiates affection, and the truncated name is priceless. So are “Rajagopala”, “Rajagopalan”, “Rajagopalachari”, “Rajagopalacharya” and “Rajagopalacharjee”.

I was not blessed with a banyan tree under which I could find enlightenment. All it took was a bigot to open my eyes and make me cherish the names this city has gifted me.