In the middle of an ever-expanding concrete jungle in Beliaghata stands Hyderi Manzil, a 400sqm, single-storey, 19th-century structure on a 1,000sqm plot.

Now better known as Gandhi Bhavan, this building — a rundown and virtually abandoned structure then at the heart of what was Mianbagan — is where the “Miracle of Calcutta” took place in September 1947.

Coined by Manubehn Gandhi, the epithet refers to a series of events that occurred over a 26-day period, culminating in a frail Mahatma’s single-handed rescue of Calcutta and Bengal from a frenzy of communal violence.

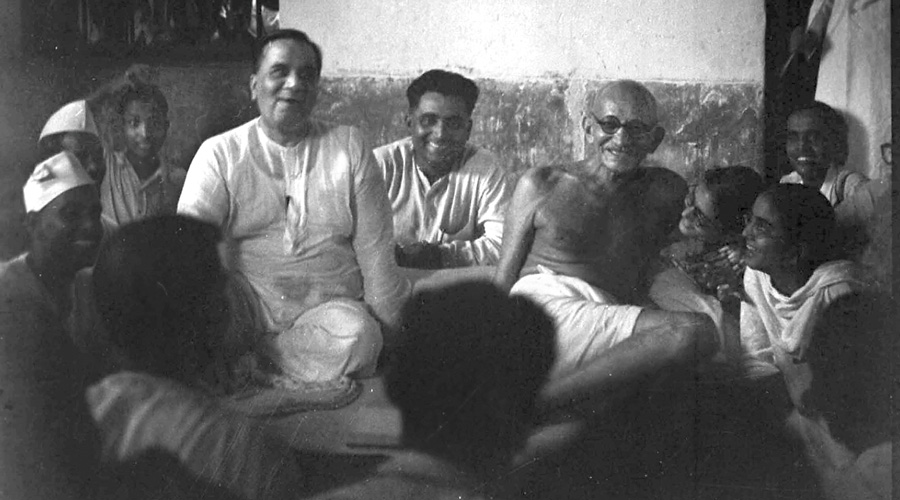

It was in one of Hyderi Manzil’s eight rooms, cleaned up to make it relatively liveable, that Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi spent the tumultuous period between August 13 and September 7, 1947. Staying with him was the Muslim League stalwart and head of the (undivided) Bengal provincial government, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy.

It was in this mansion that Gandhi personally brokered peace between Hindus and Muslims, fasting for 73 hours until key leaders of the warring groups had laid their arms down at his feet and sworn off communal violence on September 4.

On September 7, Gandhi was quoted as telling a large gathering at the Ochterlony Monument (now Shaheed Minar): “Even if you want to fight, against whom will you fight? Against your own brothers? I request those who have weapons to surrender them. Weapons will not save anyone; God alone is the saviour of all, so seek His protection.”

The colonnaded Hyderi Manzil, with wooden louvres on the facade, was presumably an outhouse surviving from a much larger property that members of the Dawoodi Bohra community from Surat had bought in the middle of the 19th century.

However, the Hyderi Manzil sequence in Richard Attenborough’s 1982 film Gandhi was shot not in Beliaghata but in Mumbai.

In one scene, just before breaking his fast, Gandhi talks to Nahari, a fictional Hindu rioter who has murdered a child after his own son was killed by Muslims. The Mahatma asks Nahari, played by Om Puri, to adopt a Muslim orphaned by the riots and raise him as his own, and raise him as a Muslim.

Historians said Hyderi Manzil had indeed witnessed many such incidents during Gandhi’s September 1-4 fast.

“In many ways, the building bears witness to a brief but vital chapter of history that may be deemed a beacon of light in what was perhaps the darkest hour for modern South Asia,” a Calcutta-based political scientist said, requesting anonymity.

“The Sangh parivar would like people to forget such chapters of history and remember only what suits the Hindutva line.”

He added: “Despite the dubious role the likes of the RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha had played through the 1940s, the saffron ecosystem today stresses only the League’s responsibility and some questionable acts by the Congress. This (propaganda) has been a discernible part of the saffron bid to win Bengal.”

The Hyderi Manzil stay marked Gandhi’s last visit to Calcutta, a city he had toured at least 64 times from 1896 and where he spent a recorded total of 566 days.

Several historians have underlined that Gandhi chose the location, then primarily a Muslim neighbourhood, for his stay as it had witnessed considerable violence during the 1946 Calcutta Killings.

Gandhi spent August 15, 1947, the day of India’s Independence, fasting and praying.

Historian Sugata Bose, grandnephew of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, said it was the Mahatma’s moral force that ensured peace in Calcutta on August 15, 1947.

“Gandhi published an editorial titled ‘Miracle or Accident’ on August 16, the first anniversary of the Great Calcutta Killings, in which he narrated how Hindus and Muslims had chanted ‘Jai Hind’ in unison. It was neither miracle nor accident but the willingness of human beings to dance to God’s tune. ‘We have drunk the poison of mutual hatred,’ Gandhi wrote, ‘and so this nectar of fraternisation tastes all the sweeter, and the sweetness should never wear out’,” said Bose, the Gardiner Professor of Oceanic History and Affairs at Harvard University.

Echoing Bose, a city-based social scientist said the Mahatma’s role had been of immense importance to Bengal and Calcutta, perhaps for the rest of the country.

She said: “On September 7, 1947, Gandhi said: ‘Let us work with God as witness. Bengal must remain calm, even if the whole of Hindustan is reduced to ashes…. It would be wonderful if the Muslims and Parsis are as free to read the Koran and the Zend Avesta as the Hindus in Bengal are to read the Gita, to recite the Gayatri and perform sandhya.’ That is the Bengal he had envisioned, even after the Partition brutally dismembered it.”

Senior historian Rajat Kanta Ray said Gandhi’s tactic was to avoid getting into the reasons for the quarrels and peacefully negotiate a compromise.

“He did it very successfully in Noakhali and Calcutta, for instance,” said Ray, professor emeritus of history at Presidency University and former vice-chancellor of Visva-Bharati.

“Regrettably, there’s nobody left like that nowadays. Least of all, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has been trying to appropriate some of Gandhi’s sermons while growing a beard like that of Rabindranath Tagore.”

Ray added: “No matter how hard he tries to compare himself to the Mahatma or the Kabiguru, I do not believe the people of India, or Bengal, will accept that.”