A black Phillips transistor that my father brought one evening on his way home from the factory he worked at was for years my only window to any form of entertainment.

The black and white Televista TV set we purchased in 1985 could not replace it. Not till the transistor fell completely silent, exactly when I can’t remember now. And along with it went the voice, a voice that introduced me to the magical world of cinema. Hindi cinema to be precise, which was mostly looked down upon.

That voice was Ameen Sayani’s.

“Medium wave do sau unnees teen meter, yaani ek hazar teen sau atsath kilohertz par yeh Vividh Bharti ki vigyapan prasaran sewa ka Dilli Kendra hai. Aaiye ab sunte hain prayojit karyakaram,” after which Ameen Sayani would take over.

Those "prayojit karyakrams (sponsored programmes)" on Sunday afternoons were my window to Hindi films. Though my parents were regular film-goers and I often accompanied them, but for a lower-middle class family to watch each and every new release in the eighties was not an easy task.

Ameen Sayani’s narration helped me imagine how the action unravelled on the screen for all those unseen films which I went to see much later as an adult. While many would and probably still call Hindi cinema's biggest superstar "Amitabachchan", I learnt to pronounce the name as Amitabh Bachchan from Ameen sahib. For, he would always stretch the "taa" for dramatic effect.

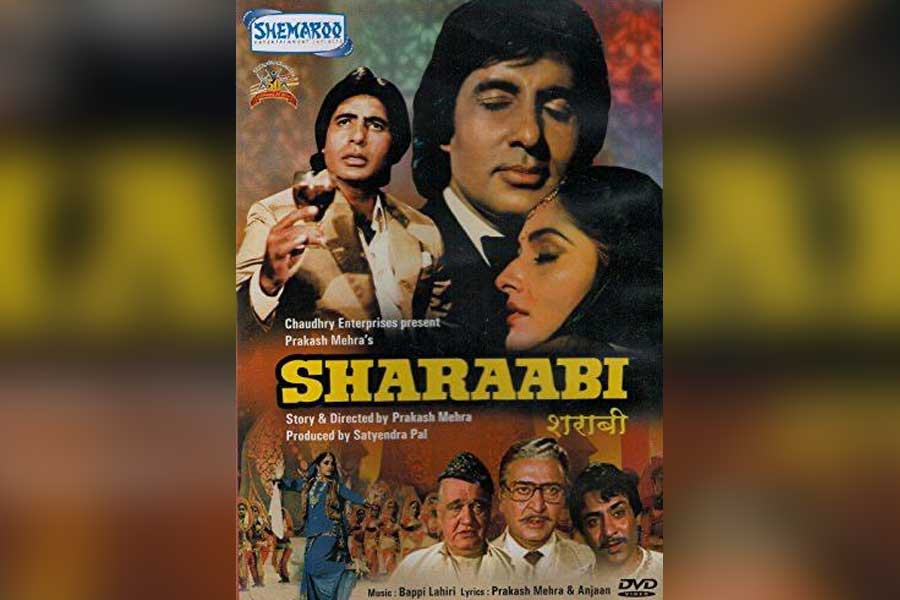

Film poster. Wikipedia.

Those were the early 1980s (I was born during the Emergency). Television sets were still a luxury for most households across India. Radios and transistors were the most popular source of entertainment.

My childhood and early youth were spent in a small industrial town in Haryana bordering Delhi. There were many single-screen theatres in the township, made for refugees coming from Punjab, and turned home for people from all over the country.

Me, still a young boy, didn’t know the voice, or anything about the man who introduced me to the world of Hindi cinema, instilled a love, a fascination and an obsession. Apart from films, the characters from Diamond Comics created by cartoonist Pran, also occupied a large space of the airwave on those Sundays.

Post mangsho-bhaat, Sunday afternoons, between homework, I would be glued to that black transistor listening to Ameen Sayani speak about the latest Hindi film release, like Sharaabi for instance (which I recall listening to), or an upcoming one in about 15 minutes or so. Most of the other films featured have slipped through the tricky cracks of memory. The radio ads for Mugli Gutti 555, Mohan Ghee and some others have somehow stayed on. Others I would need some help to recall today.

In those days, film promotions (I doubt if it was called so) had very limited options. There were the advertisements in newspapers, hand-drawn posters pasted all over towns and cities on billboards, any wall available, the bi-weekly Chitrahaar (every Wednesday and Friday on Delhi Doordarshan) that would play at least a couple of new songs and Ameen Sayani’s voice on Vividh Bharati.

He would introduce a film with the phrase “banner parcham-tale” which I later learnt was a reference to the producer. Then he would go on to narrate a bit of the film’s story mixed with dialogues and some songs, talk about the actors, the lyricist, music director and the director. He would end each programme with a cliffhanger, a question mark on what I later learnt while writing screenplays was the quest of the film’s hero, whether he will succeed. Yes, he would encourage his listeners to watch the film on the big screen.

A school student like me could only watch one or two in a year on the screen. His famous “behenon aur bhaiyon” did not include kids like me.

“Chunanche jab Bharti ne suna…” I remember him talking about the 1990 release Azad Desh ke Ghulam, referring to the female lead played by Rekha. Many years later I learnt the meaning of Chunanche and an RD Burman composition made me aware Chunanche should not be used along with Goya ke.

I remember an episode of a mock-court proceeding aired on Vividh Bharati, called Filmi Muqaddama, sponsored by the textile brand S Kumar, where he chided a young Anu Malik for not singing more often.

Then I had no idea what cinema would eventually come to mean to me. And I owe a great deal of it to Ameen Sayani, a man I never met, even though I lived in Mumbai. As a child, I was so drawn into the world of Hindi films that I kept a notebook where I would write any one piece of dialogue from a film that I got to see on a neighbour’s television set or our own one later, using a sketch pen, each letter with a different colour.

Sadly, an uncle of mine found that notebook and it was confiscated. Much later in my diaries I started writing down the lyrics of old Hindi film songs.

In the Haryana town that I grew up, I have grave doubts if anyone knew the name of Luis Bunuel or Francois Truffaut or Dario Argento or Sam Peckinpah. I certainly didn’t. I had no idea about world cinema then. One window led to another. One seed led to another. And I owe that first love, possibly the only love of my life, to Ameen Sayani.

So long, Ameen sahib.