Once when Satyacharan Sardar was travelling by local train, he heard a child ask his mother, “What does a tribal look like?” The mother replied, “Ashobhyoder moto”. Meaning, like the uncivilised. Satyacharan, an Adivasi and a government schoolteacher, is talking about the enduring typecasting of tribal people. He continues, “To date, during Durga Puja, it is the asur or demon who is shown to be killed. Do you know Asur is the name of one of the tribes? Durga’s asur also has a physical resemblance to the tribal man.”

On the other end of the spectrum is the idea of tribals as emblematic of pastoral life, creatures of the wild who dance and sing and drink hadiya and make merry.

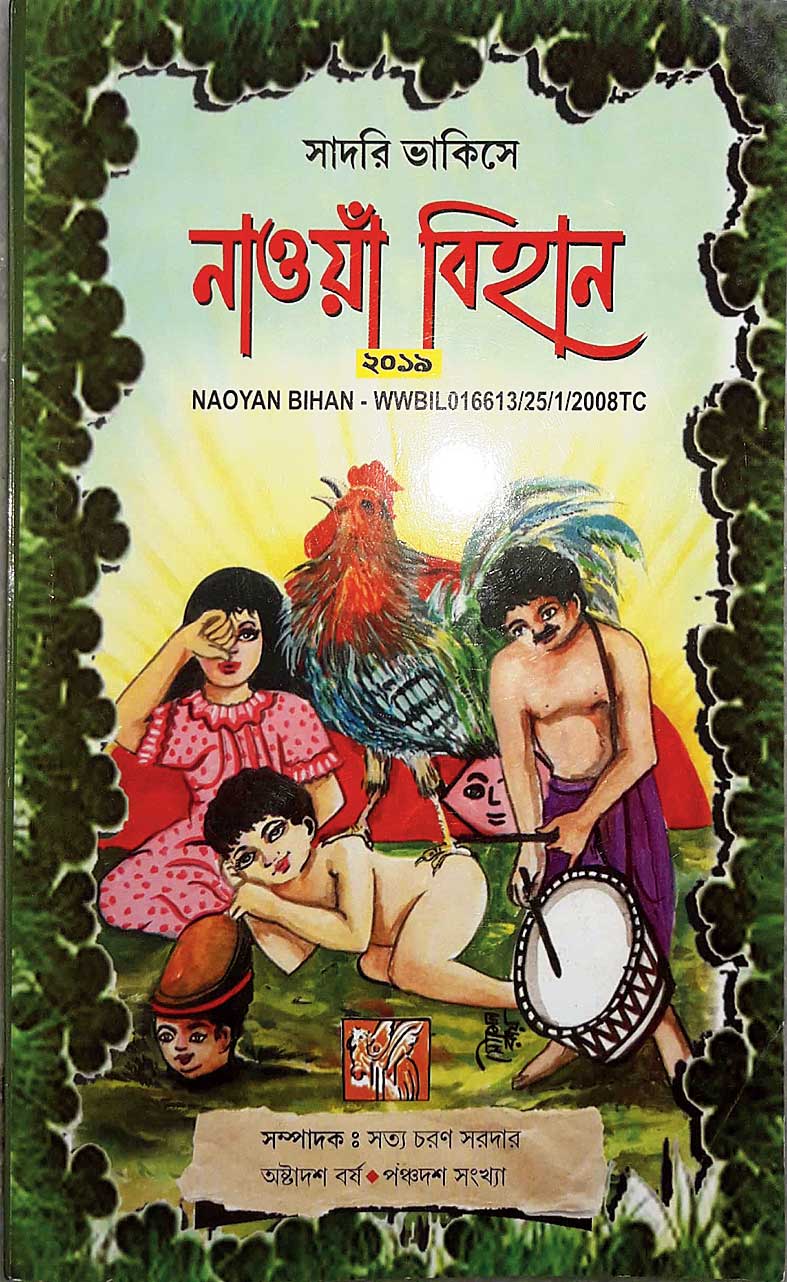

Nawa bihan means notun shokal or new morning in Sadri, which is the most spoken language among the tribals of south Bengal. In 2001, Parimal Sardar, along with some others from the community — Sambhunath Sardar, Dilip Sardar, Rajkumar Sardar, Tapan Sardar, Satinath Mahato, Gour Chandra Sardar and Prafulla Sardar — decided to float an annual magazine named Nawa Bihan. Other than Prafulla, who was at the time employed with the Indian Railways, all the others are schoolteachers.

Nawa Bihan co-opted community elders to recount community wisdoms and practices and named the exercise Baikal Ghari Kahati Courtesy, Nawa Bihan

“The purpose of the group was to spread awareness among our own community — about who we are, what our culture is, what our faith is. And this we decided to do by writing about our socio-cultural background,” says Parimal.

Today, Nawa Bihan has assumed the shape of an organisation working to correct the perceptions about tribals. The group works primarily in the South 24-Parganas, which is home to the Munda, Bediya, Bhumij and Oraon tribes. Recently, they have also started reaching out to the people of north Bengal. Satyacharan is also a member of Nawa Bihan.

There are 40 Scheduled Tribes in Bengal. According to the 2011 Census, West Bengal has a tribal population of 52,96,963, which is about 5.8 per cent of the population of the state.

Says Parimal, “Education reached our community rather late, almost three decades after Independence. In the 1980s, the number of tribal students appearing for school-leaving examinations was not even one in a hundred.” Those in the community who received education, according to him, now felt embarrassed of their own community and preferred to keep their distance.

The need to mingle with the mainstream drove them to do different things — have Brahmins officiate over birth rituals, weddings and deaths; participate in Durga Puja and Kali Puja; traditional mores began to wear, spoken tongues — Sadri, Mundari — fell to disuse.

Two decades later, there seems to be a change of heart. Some of those who had gone to school and received higher education, such as the members of Nawa Bihan, decided to make amends. Points out Parimal, “By this time, more children from the community had started going to school. We decided to tell our own people how rich our culture was. It is not achal or redundant, it is not something they could not be proud of.”

Nawa Bihan co-opted community elders to recount community wisdoms and practices and named the exercise Baikal Ghari Kahati Courtesy, Nawa Bihan

And what did Nawa Bihan achieve with the patrika they brought out? The magazine was meant to chronicle community narratives as well as community dialogues and perceptions from within the community and outside. “Since 2001, we have had articles in Bengali and Sadri alike. But now that we want Sadri to be accepted as one of the mainstream languages, we are encouraging people to write in Sadri mostly,” says Satyacharan.

The 2019 edition was an all-Sadri edition. Some of the titles from it are: A Commission for Adivasis by Umapada Panigrahi, The Culture of the Adivasis of the Sunderbans by Satyacharan Sardar, The Untold History of Adivasis by Prafulla Sardar. The magazine is distributed free of cost in the Sunderbans, various places in the South 24-Parganas, Bankura, Purulia, and more recently Darjeeling by members of Nawa Bihan. They have also made a list of their own who are now recognised members of the mainstream. Copies are distributed at festivals and gatherings. “The reaction has been mixed. Some people want to be identified as Scheduled Tribes only to reap the benefits of reservation; this kind ignored our efforts to reach out. But the school-going, college-going lot welcomed it.”

Next, they began reaching out to those on the ground and they started with teenagers. “We tried to attract them through sports,” says Parimal. He continues, “We would organise football tournaments, but the selection did not hinge on who played well. We would interview the candidates and ask them questions about their own culture, talk to them in Sadri and only those who knew the answers were picked. Those who did not know could go home, ask their parents about their roots, read the magazine, and again submit to a selection process.”

The third thing that the group did was to co-opt community elders. This programme, called Baikal Ghari Kahati, which roughly translates to wisemen speak, was meant to be an exercise in recounting community wisdoms and practices.

The tribals had come to believe that they are Hindus. Now, the elders spoke to their young about their animistic faith and corresponding rituals. How their forefathers would build thaans, or small mounds, of mud to represent the forces of nature and celebrate them in their own way. There was no idol worship as is common today. Says Parimal, “Our rituals are quite different. In a few days it will be Manasa Puja. Hindus too celebrate this festival but their rituals are different. In our culture, we take a duck and worship it, we feed it rice grains and then sacrifice it. The community consumes the cooked meat as prasad.”

The Baikal Ghari Kahati sessions brought to light other treasures. How in the old days whenever there was a wedding, people would extend financial help to the family concerned. Satyacharan speaks of how people would bring their own food and have a community feast instead of having any one family host the entire community. He adds, “Similarly, if someone from a poor family died, it was customary to let the family fulfil all obligations to society by serving only one house in the neighbourhood.”

From birth to marriage to death, the tribal community observes many a ritual. Says Satyacharan, “In the tribal set-up, there is no concept of Brahmins overseeing milestone social functions. And there is no particular class in the tribal society earmarked to act as priests.” Parimal explains, “Anybody who has learnt the rituals can become a pahan or purohit in our community. It is the knowledge that matters.”

And so the struggle, or as Parimal puts it, “Our laadai continues.” He pauses and then adds, “Our laadai to overcome a mountain of shame.”