Prostitution and sex work flourished in 19th-century Calcutta and its suburbs. Trafficking of child widows was rampant and with the abolition of Sati, many “rescued” women were forced into the sex trade. A mid-18th century colonial survey found that out of 12,000 sex workers, 10,000 were Hindu widows and most of them below 18. The profession was so profitable that even aristocratic families rented out their premises to sex workers. But that was not all.

Recently, DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery) organised an event titled “Sundaris in Song”. Sundari was how the babus referred to prostitutes. The symposium held at the Academy Theatre Archive in Howrah was an attempt to showcase these women and their contribution to the music scene through a series of images created between the late 18th century and early20th century. This includes some of the earliest visual representations of sex workers.

These women first appeared in pats, miniaturised traditional paintings sold around Kalighat temple. The patuas or artists painted images of Kali and other divinities and sold them as souvenirs to pilgrims. Later, sensing the changing taste of prospective buyers, they started experimenting with other subjects — satires on urban life and erotica.

According to Shatadeep Maitra, who is project manager – exhibitions at DAG and has been working on this collection, non-religious themes in Kalighat pats generally appear in the last quarter of the 19th century. He says, “Sundari images are not portraits but depict sex workers in a pin-up style of art based on the imagination of the patuas.”

The Kalighat pats slowly went out of fashion with the advent of lithographs, especially the coloured ones, called chromolithographs. Then there were oleographs, a refined version of lithographs, perfected by artist Raja Ravi Varma in Mumbai. “These techniques involved the use of multiple lithographic stones, sometimes as many as 30, with one stone for each colour to be rendered in the final image,” says artist Aditya Basak who grew up watching how these techniques were mastered by the craftsmen near his home in the Chitpore area, where Battala printing flourished. “We also learnt the basics of the technique at the Government College of Art and Craft as students,” he says.

Photography arrived in Calcutta in the mid-18th century and studios such as Bourne and Shepherd organised shoots for many of these women.

Annada Prasad Bagchi, who trained at Calcutta’s Government Art School, founded the Calcutta Art Studio in 1878 in Bowbazar with four of his students. Its two-storey building still stands and is now owned by Shubhojit Biswas, the great-grandson of Naboo Coomar Biswas, one of the co-founders of the studio. Biswas says, “My ancestors primarily printed chromolithographs of gods and goddesses based on stories from holy scriptures. But there were possibly a handful of pictures of some women, commissioned by babus.”

So there were photographs of Pramoda Sundari sitting on the floor and combing her hair and Kumada Sundari looking seductive in a white sari with a black border, a betel leaf in her hand. Most of them were printed either at Chorebagan Art Studio or Kansari Para ArtStudio in central Calcutta. Today, most of the Sundari pictures are in the collection of DAG, British Museum and Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Maitra, who has been working on this collection of images, also believes the images of these sundaris were for private viewing of the babus in the nautch ghar. But writer and expert on 19th century Bengal Arun Nag doesn’t agree. He says, “Babus would rather buy erotic pictures and even marble statuettes of women from auctions in Europe rather than display local lithographs.” Nag believes the lithos were meant for a middle or lower-class clientele.

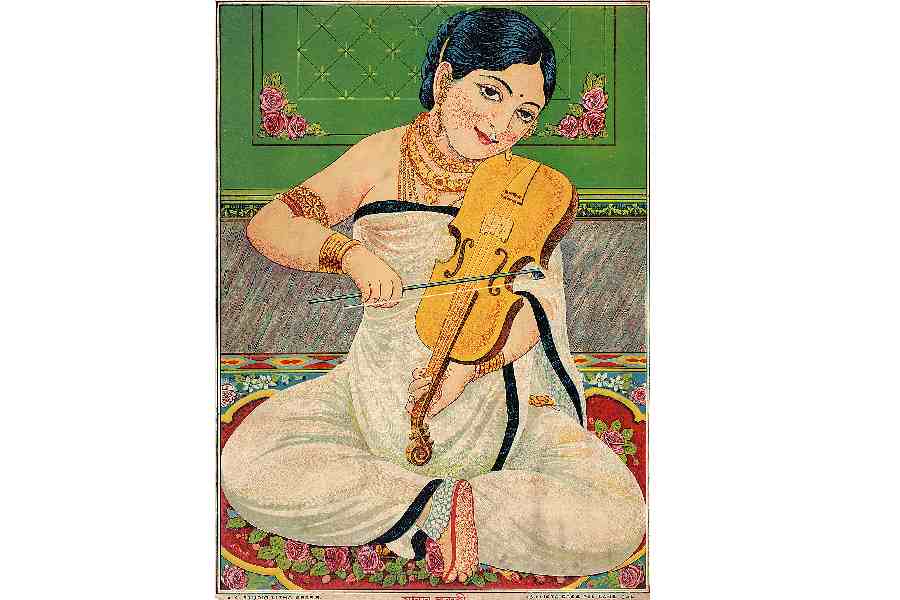

The most striking images at the exhibition are of Manada Sundari, a woman playing a violin, and Nalini Sundari, a woman at the tabla. These pictures gesture at the transformation of prostitutes into musicians. Devajit Bandyopadhyay, who is the founder and director of the Academy Theatre Archive, says, “Baijis and courtesans should never be confused with common prostitutes. They are custodians of rich music and dance.” Bandyopadhyay has a compilation of Bengali theatre songs of the 19th century titled Bai-Barangana Gatha. At the symposium, he described how some prostitutes found the platforms of theatre, music, movies and circus to liberate themselves and carve out a more creative career as independent artistes.

Sumantra Banerjee, who has researched the elite as well as popular culture of 19th century Calcutta, writes in his book Dangerous Outcast: The Prostitute in Nineteenth Century Bengal: “There was an explosion of morbid curiosity and prurient voyeurism around the prostitute’s lifestyle — in the Bengali chapbooks and farces that flowed from the cheap printing presses of 19th-century Calcutta and other towns.” Voyeuristic pleasure of middle and low-income people largely inspired them to secretly collect erotic pictures of sundaris.

One picture in the collection of the Academy Theatre Archive shows Rani Sundari, a little-known singer and theatre actress, standing attired in a white sari and a dark petticoat in a confident pose. Says Bandyopadhyay, “These emancipated women had no qualms in posing for photo shoots to publicise their talents.”