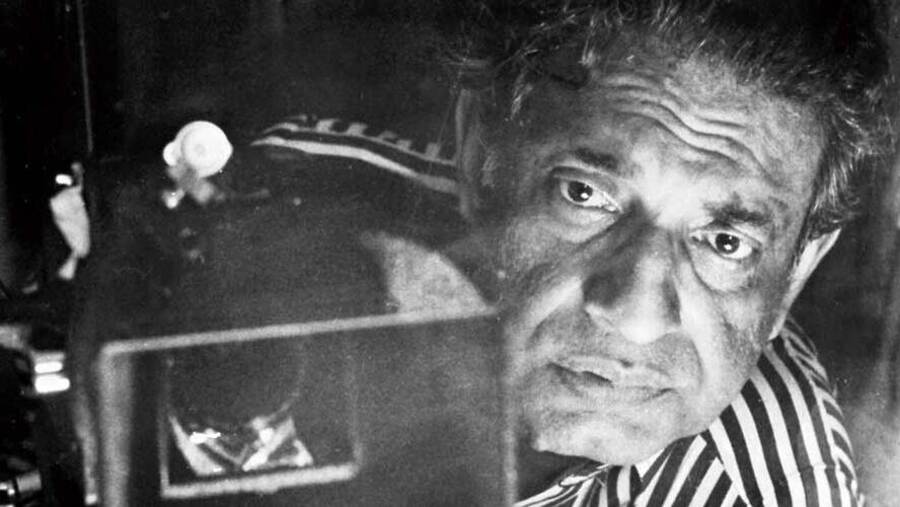

Adoor Gopalakrishnan, considered the pioneer of New Wave cinema in Malayalam, feels Satyajit Ray is the most original Indian filmmaker.

Ray’s Pather Panchali was a starting point for Gopalakrishnan’s own filmmaking.

“Ray is the most original filmmaker in Indian cinema,” Gopalakrishnan said at a news conference in Calcutta on Monday afternoon. He was in the city to speak on the occasion of Satyajit Ray’s birth anniversary.

Ray brought to cinema a background of writing, literature, children’s literature, illustration, painting and an education at Santiniketan. “He always wrote the scripts of films he had seen.”

Ray admired Gopalakrishnan’s films, even making the effort to come to the screening of his Mathilukal (1990, based on Vaikom Muhammad Basheer’s autobiographical novel) in Calcutta.

Ray was ill but walked up the stairs at Gorky Sadan. After the screening, “he came up to me and said: ‘Marvellous, Adoor, marvellous’”.

Ray would always watch Gopalakrishnan’s films and discuss them enthusiastically with the younger director.

“The first of my films that he saw was my second, Kodiyettam (1977). I was not imitating him. I was on my own. Probably that is why he liked me,” said Gopalakrishnan, sprightly at 81, with a voice full of laughter as always.

He remembered watching Pather Panchali (1955), Ray’s first film, for the first time in the late 1950s. He watched it at the Gandhigram Rural Institute in Madurai, where he was a student. He was interested because he knew that “a student from Santiniketan had made the film and he got some award abroad”.

He watched it without subtitles, on a 16mm print from the government of Bengal, screened on a wall.

“People were talking in a strange language. We didn’t understand what was going on.”

But he was attracted to the natural surroundings — “It looked like a coastal village in Kerala” — and the faces without make-up.

“They looked real, very real. Even the wrinkled face of the old lady (Indir Thakrun). Even without knowing what she was humming I just enjoyed it,” Gopalakrishnan said.

The sequences were interesting. Two elderly persons try to talk to each other, shouting “ki” and “ki” at regular intervals, Gopalakrishnan laughed and enacted the exchange.

This film would become a centrepiece of his life. In 1961, he enrolled at FTII, Pune, in the screenplay writing and direction course, where Pather Panchali was one of the texts.

He would have to study it again and again, frame by frame, scene by scene. “The composition of each scene would be studied.”

The more he watched the film, the more he appreciated it, its humour and its beauty, such as in the scene announcing the arrival of the rains.

The first drop of rain, dramatically, falls on the bald head of a man. “Again in the rain you see the dance of the water insect. Visually it is so beautifully made.”

Other than scenes like Durga’s death, most of the film was shot outdoors, “by someone who never lived in a village”, Gopalakrishnan laughed. Ray’s crew for the film too was full of first-timers.

“It was not a repair, it was not a continuity. It was just something originally done,” Gopalakrishnan said.

But he never offered his opinion on Ray’s films to Ray. “How could I? He was my guru, (Ritwik) Ghatak was my teacher, Mrinal Sen was my elder brother,” Gopalakrishnan said.

Ray had been surprised by Gopalakrishnan’s restrained use of background score. Gopalakrishnan uses it sparingly, because he does not want the score to “underscore” something too much or become a key, such as “sad music”, for the audience to interpret a feeling.

He is strongly opposed to the Centre’s ideas about film archives. “They have to be under the government, not a corporation,” he said.

Gopalakrishnan does not have much faith in films on the OTT platform. “Cinema will stop being cinema” if not shown on the big screen, he said.

“The darkness, the people, the communal viewing, the highest and the lowest levels of sound” create “a magic and a mystery” that is never at the command of the small screen.

On the current crop of propaganda films for Hindutva, he said no filmmaker with any integrity would make such films.