Twin branches of Bangladesh national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam’s family, living on both sides of the barbed wire fence, came together in Calcutta on Thursday to condemn the “distorted” AR Rahman rendition of Nazrul’s patriotic song Karar Oi Louho Kopat in the war biopic Pippa, demanded immediate removal of the song from the movie and all digital platforms while threatening to sue the producers in courts in both countries.

In the process, the disgruntled descendants of the poet ended up lambasting the poet’s eldest grandson, Anirban Kazi, who signed as a witness to the purported contract for the song’s adaptation and recreation license inked between Kalyani Kazi, Nazrul’s daughter-in-law, and the producers of the film in September 2021 in exchange of Rs 2 lakhs. Kalyani passed away in May this year, ahead of the release of the film. The copyrights of Nazrul’s works, currently held by the poet’s legal heirs, would expire in 1936.

Exposing sharp rifts within the family, Kazi Arindam, the poet’s younger grandson, and Khilkhil Kazi, Nazrul’s Dhaka-based granddaughter, also confirmed their intentions to move court against Anirban for giving his consent to what the annoyed family wing felt was an “abominable act”.

Khilkhil Kazi (left) and Kazi Arindam addressing reporters in Calcutta on Thursday.

The developments came within 72 hours of Pippa makers tendering a public, albeit qualified, apology in the wake of the large-scale social media backlash that the interpretation of the song’s original composition had evoked where the marching tune of the song was recast by the Oscar-winning music director into one of Kirtan style, a Bengali folk rendition for prayers. Produced by Ronnie Screwvala under the banner of RSVP Movies and Siddharth Roy Kapur's Roy Kapur Films, and directed by Raja Krishna Menon, the film features Ishaan, Mrunal Thakur, Priyanshu Painyuli and Soni Razdan in pivotal roles.

The Allegation

“We had no idea that the rights of the song were sold until someone made me aware about the film’s release on November 9,” claimed Arindam. “I got in touch with my brother immediately and he said that the contract was signed by my mother with him as witness. But I have serious doubts about my mother’s involvement in this since she would never have allowed such a travesty to take place,” he added, claiming he managed to get hold of the contract from Anirban a day later after much persuasion.

“The allegation that the family has sold out Nazrul is incorrect since no one in the family was involved except my brother. He should shoulder the entire responsibility for all the controversy that’s taking place because this has badly hurt the sentiments of Nazrul lovers,” Arindam maintained.

“Had the filmmakers done minimum research on the context in which the song was written, they would not have the audacity to distort it like this,” chipped in Khilkhil Kazi who heads the Kabi Nazrul Institute in Dhaka. “How can a warrior song, meant for the rebels who took on the British during the freedom struggle and which has continued to inspire millions of people of this subcontinent ever since, be de-contextualized and cast in the tune of a Bengali folk song?” she asked.

The Contract

The purported copy of the contract claimed to have been accessed by Arindam, however, grants the producers rights of “use, adapt and re-create the literary work as part of a musical composition” and “edit, re-format and/or shorten the literary work for the aforesaid purposes”.

Purported contract between Kalyani Kazi and Pippa producers

The contract, interestingly, is countersigned by Anirban as witness on September 4, 2021, four days prior to the official contract date of September 8, while the authorised signatory space for Roy Kapur Productions remains blank. Kalyani Kazi’s signature on the contract bears no date. Although addressed to Kalyani Kazi, the contract mentions Kazi Nazrul Islam as “your grandfather” which, the dissenting family wing claimed, was actually intended for Anirban and not his mother.

“We have enough material to make out a legal case against the producers that this contract is untenable in the eyes of law,” Arindam maintained.

“The contract renders us as third parties and indemnifies the producers against any claims made by other relatives of the family. How are we responsible then for the outcries against the song/” said Avipsa Kazi, Arindam’s daughter. “Why did my uncle not keep a clause in the contract to review the song once before it was published?” she asked.

Anirban’s defense

“It was my mother who signed the contract, not me. I merely signed it as a witness,” said Anirban. “My mother was in sound mental and physical health when she signed the contract. She should have informed other members of the family. What can I do if she didn’t?” he argued.

“There’s an unwritten contract between the two sides of the family who are living on two sides of the international border. While my mother issued rights for use of Nazrul’s works in India, my aunt and subsequently my cousin Khilkhil and her institute did the same in Bangladesh. I have information that she has sold Nazrul’s literary rights to private entities in that country. I have never questioned her intentions,” he added.

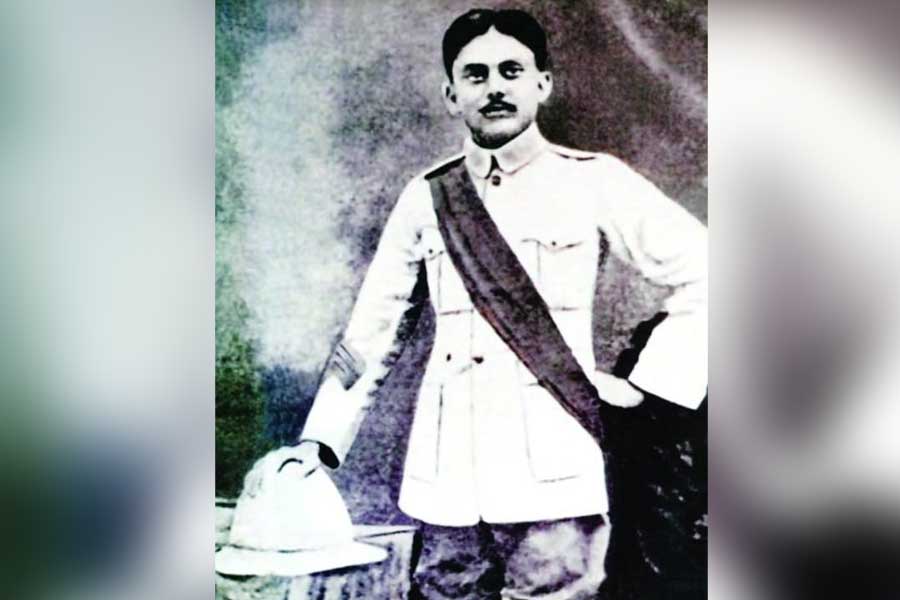

Nazrul Islam in military uniform. Photograph taken after his return from services.

“I have my defense ready and will answer my relatives in court, should they make that move,” he stated, adding: “This murky affair will actually move Nazrul lovers away from the poet because they would think twice before getting dragged into a possible mess.”

Anirban, however, agreed with his detractors that the Pippa rendition of the song was “horrible”. “My mother had allowed the usage of the song in good faith thinking the makers would revive the popularity of the song among the current generation. I shudder to think what she would have felt today if she were alive,” he said and added that he planned to be part of a formal protest to the PMO, Union cultural ministry and the censor board.

“I have already asked producers to drop the names of me and my mother from the ‘Special Thanks’ acknowledgment of the movie’s credit title,” said Anirban.

Historical context of Karar Oi Louho Kopat

Circa 1921. Nazrul, then a fiercely patriotic youth all of 22 who had just returned home from his mandatory military services, was sharing a rented house with Communist leader Muzaffar Ahmed in College Street in Central Calcutta. On December 10 that year, the British police arrested Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das for leading the Swadeshi movement and initiating the ban on British-made clothes to switch over to Khadi. Following his arrest the responsibility of publication of Banglar Katha, a magazine published by the leader, was taken up by Das’s wife Basanti Devi who approached Nazrul for a piece of writing for the magazine’s forthcoming edition which was planned on pieces from writers and influencers who were close to the leader.

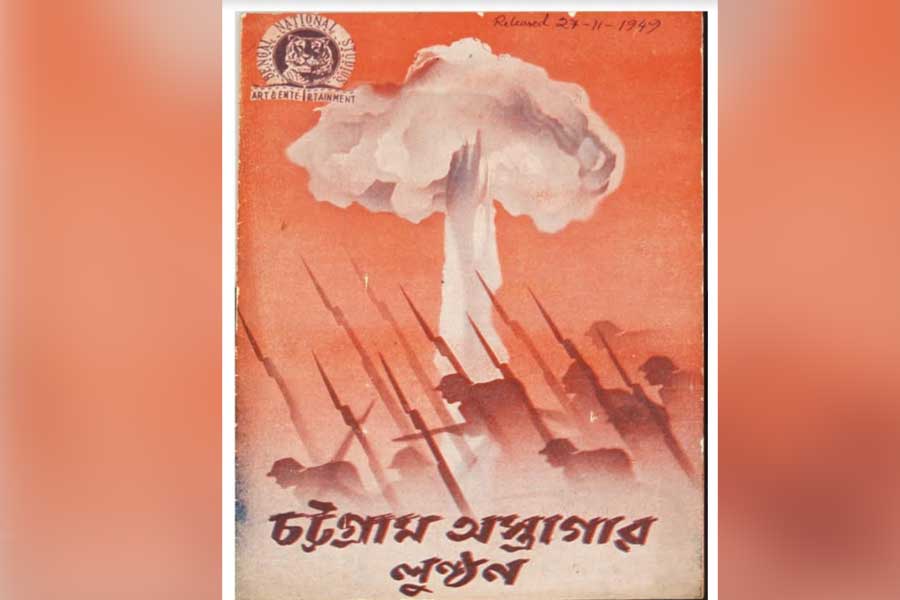

Film booklet cover of Chattagram Astragar Lunthan, 1949

The poem was hand-delivered to Basanti Devi on a piece of paper and published in Banglar Katha on January 20, 1922. Put to the tune of a marching song, purportedly by Nazrul himself, it immediately became popular among freedom fighters, jailed or otherwise. Leaders like Subhash Chandra Bose and Chittaranjan Das reportedly sang the song regularly when they were incarcerated in British prisons. The piece was included in Nazrul’s poetry collection, Bhangar Gaan, published in 1924 but soon banned by the colonizers. The book wasn’t republished till after Independence but the song had, by then, already become a cult.

In 1949, Girin Chakraborty recorded the song on the Columbia Record Company label and was, in the same year, used in the film 'Chattagram Astragar Lunthan' which depicted the Chittagong armoury raid by a motley band of daring extremist freedom fighters led by Masterda Surjya Sen. Both events only added to the song's never-diminishing traction. Interestingly, the title on the vinyl was spelled as ‘Kobat’ instead of ‘Kopat’ suggesting colloquial pronunciation of the word and the song was termed Jatiya Sangeet, National anthem.

"Times have changed and in today's digital ecology, AR Rahman is far more popular than Nazrul. Hence by sheer algorithmic programme, the distorted version would reach more people than the original one," said Arka Deb, Nazrul researcher, explaining the possible danger of the original version getting lost to posterity.

What next

To avoid a possible repetition of what she called a ‘faux pas’, Khilkhil Kazi insisted on forming a Board for providing publication rights of all literary works of Nazrul on this side of the border in line with the one which exists in Bangladesh. “Let chief minister Mamata Banerjee ensure that some members of the Nazrul family remain part of that board along with other experts,” she said. Her call, interestingly, was also echoed by Arindam Kazi.