Leukemia is cancer of the white blood cells – cancer in one of the most explosive, violent incarnations… In the long, bare hall outside Carla’s room, in the antiseptic gleam of the floor just mopped with diluted bleach, I ran through the list of tests that would be needed on her blood and mentally rehearsed the conversation I would have with her. There was, I noted, something rehearsed and robotic even about my sympathy.

In his book, Emperor of Maladies, a meticulous, unsentimental but humane biography of cancer, Dr Siddhartha Mukherjee is often called upon to draw upon his reserves of empathy as an oncologist. How do you break bad news? In the context of the horror at RG Kar Medical College and Hospital, this question has come to the fore again, albeit under different circumstances.

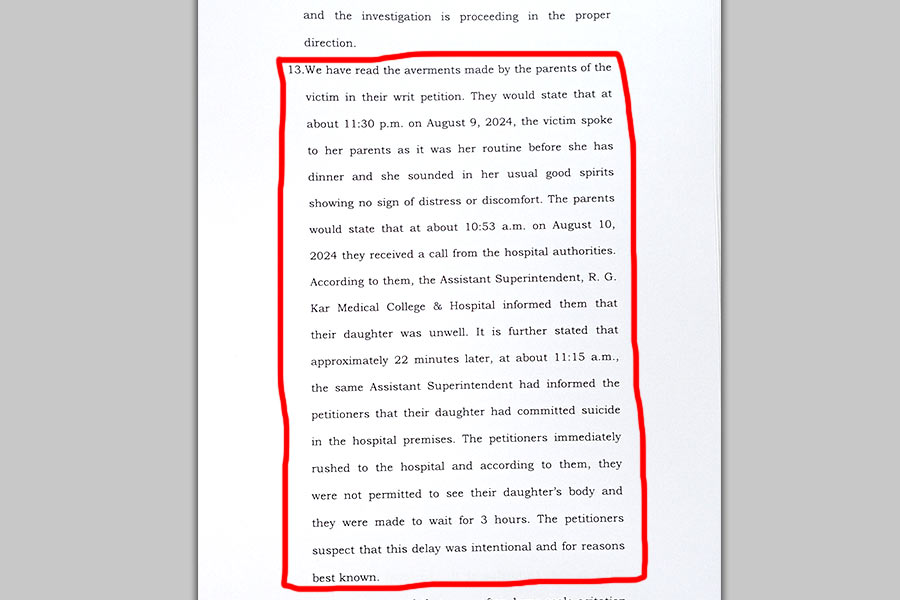

On the morning of August 9, the authorities at the state-run medical college thought it fit to break the news to the parents of the post-graduate intern who had been raped and murdered on campus on the phone. First call: Your daughter has fallen ill. Second call (about 22 minutes later): She has died. She committed suicide.

The suicide claim, by the hospital’s assistant superintendent, who has subsequently been verbally chastised for irresponsible conduct by the Supreme Court, is at the top of a series of revelations that have heightened apprehensions of a cover-up with accusatory fingers being pointed primarily at the West Bengal government and the Kolkata police who are under the direct supervision of chief minister Mamata Banerjee by virtue of her holding the home (in addition to health) portfolio.

Customary denials have followed from both, the chief minister undertaking a protest march in the capital of the state she runs and the Calcutta police commissioner issuing angry statements against the media and social media users. After initial dithering, the health authorities have found an explanation for coming up with the suicide claim. “There was no malafide intention in this,” said an official, going on to add, as bizarre as it may sound, that the assistant superintendent mentioned suicide because it was “tough to tell the parents over the phone that their daughter was raped and murdered”. In other words, what the health department was trying to convey was that mentioning suicide as the cause of death instead of rape and murder was a way of softening the blow for the parents of the deceased.

However, given the way the case began to unravel with the state government initially laying out a protective ring around the tainted college principal by transferring him to another college, the Calcutta High Court stepping in and transferring the probe to the CBI and the subsequent surfacing of discrepancies in the timeline of events, the health department’s defence of its bid to soften the blow with a suicide claim rings hollow, vile and downright insensitive.

For, there are ways of doing so. Medical school curriculum includes the accepted protocol for conveying bad news. But so broken is the government health sector in Bengal, with basic systems not in place with regard to equipment, staffing and a viable duty roster, that there’s little mind space left among doctors manning the emergencies and OPDs. Even officials posted at hospitals are clueless.

A grab of the Calcutta High Court report of August 13 detailing how news of the post graduate intern’s death was communicated to her parents. TT Online

“Indian doctors are never taught to convey the bad news. Let’s face the truth.” Dr Shah Alam, professor of orthopedics at AIIMS-Delhi, was blunt. “And remember, the spectrum of bad news is wide, not just limited to death. Cancer diagnosis, a congenital heart condition in a newborn, for instance, are all examples of bad news,” said Alam who has also worked in the UK where, he noted, a student is tested on his/her ability to convey bad news in FRCS, MRCS and MRCP exams.

“The way the RG Kar incident has been handled is absolutely pathetic,” emphasized Dr Harsh Jain, a neurosurgeon at a private hospital in Calcutta with work experience of over three decades in India and the UK. “It is amply evident that breaking bad news is not built into the Indian healthcare psyche. Otherwise why would someone talk this way to the parents of a deceased person? The unfortunate circumstances made it mandatory that news was passed on sensitively and in-person.”

Dr Aviral Roy, a senior critical care consultant with a private hospital in Calcutta, agreed, adding, however, that the private sector in India was at least more sensitive to the issue with some even initiating training programmes for staff. “When you come to the private sector these things matter because here you have institutional reputation to uphold,” said Roy, who studied at Stanley Medical College in Chennai, where he said he received “zero education on breaking bad news”.

Having been through the grind in Calcutta, Jain tends to be sympathetic to the plight of junior doctors and interns. Those on duty at government hospitals, he added, are so overworked and stressed at the sheer volume of patients they have to cater to that they simply do not have the wherewithal to communicate with patient families cogently and sensitively.

Dr Anand Gupta, who now resides in the US, shudders to think of his days at King George’s Medical College, Lucknow, over two decades ago. “It was a government hospital with no funds. So the moment a patient came in, the family was given a list of ten thousand things, including syringes, bloods (tests) and this and that. All of that would work out to Rs 10,000 at least in those days,” recalled Gupta, now chief of GI (gastro-enteritis) at the Syracuse VA Medical Centre in New York.

Unfortunately, things have remained quite the same in many of India’s government hospitals. A culture of apathy embedded in all levels bleeds into what is a self-perpetuating systemic malaise that has solidified into a state of permanent malignancy. But things are not as bleak at AIIMS-Delhi and other healthcare institutes of excellence. Alam agreed, attributing it to the “patience” of the Indian patient. “Anyone coming for treatment at AIIMS has to wait three hours in queue for registration, then another hour or so to reach a doctor, who invariably suggests a few tests. Another hour or so goes in getting the tests done. The patient then returns with reports after a couple of days,” he said.

India’s healthcare reality begins with the fiercely competitive medical school entrance exam and the ecosystem of specialised coaching. “The reality is so harsh that in terms of training the empathy part of it is completely taken out of the equation,” said Gupta, drawing, however, a distinction with the scenario in the West, the USA in particular, where a lot of that empathy is enforced for multiple reasons. One, the US is a litigious society. There are rules in place and those rules have to be followed. Two, perhaps more significantly, hospitals are well-equipped and work in a system where you can actually practise what you study. “And when you’re in a system and you don’t feel the system is an uncaring one it also invites you to be empathetic?”

What would have been an acceptable way of communicating with the parents of the RG Kar doctor who had been raped and murdered on campus? Gupta, Jain and Roy were in agreement that a face-to-face conversation was the starting point. The parents should have been asked to come to the hospital telling them their daughter had fallen ill and that the doctors had certain serious issues to discuss.

Once at the hospital, they should have been taken aside and made to sit somewhere so as to make them as comfortable as possible. In the West, resources in terms of a psychiatrist or a grief counsellor would have been at hand before the news was broken. “You do not sugar coat it,” said Gupta. “You don’t sugar coat anything with respect to health and diagnosis. Because that is what it is.”

The basis of their agreed upon methodology are essentially enshrined in the six-steps SPIKES protocol, the got-to guideline for breaking bad news, especially in the realm of cancer diagnosis. According to the Annals of Oncology, an online resource centre of the European Society of Medical Oncology, the acronym SPIKES refers to Setting up the interview, assessing the patient’s Perception, obtaining the patient’s Invitation, giving Knowledge and information to the patient, addressing the patient’s Emotions with empathetic responses and finally, Strategy and Summary.

Was the RG Kar assistant superintendent aware of this protocol? Going by the health authorities’ view, and that’s the charitable explanation, he/she did not. Therein lies another tragedy entrenched within the much larger tragedy of what happened to this post-graduate doctor in a government hospital in Bengal.

Over two weeks have passed since the crime at RG Kar. There’s been one arrest. Yet nothing is known about the motive and who else could have been involved. What we know, thanks to a Supreme Court hearing, is that there’s a dispute over the timeline of events that occurred after the crime was detected. For starters, the CBI version of when the FIR was lodged and the UD (unnatural death) case registered has been disputed by the state government which has submitted its own timeline to the apex court in a sealed cover. As for the police, they seem to have decided on a strategy of brazening it out over allegations of ineptitude, both in investigating the murder and handling of a subsequent mob attack on the hospital premises.

Meanwhile, how does Dr Siddhartha Mukherjee break the news to Carla? He writes in his book: I explained the situation as best I could. Her day ahead would be full of tests, a hurtle from one lab to another… But the preliminary tests suggest that Carla had acute lymphoblastic leukemia (common in children, but rare in adults). And it is _I paused here for emphasis, lifting my eyes up_ often curable. Curable. Carla nodded at that word, her eyes sharpening. Inevitable questions hung in the room: How curable? What were the chances that she would survive? How long would the treatment take? I had laid out the odds. Once the diagnosis had been confirmed, chemotherapy would begin immediately and last more than a year. Her chances of being cured were about 30 per cent, a little less than one in three.

The RG Kar doctor had no chance. She was alone, left to face her attacker/attackers who were enabled by a diseased system.

Doctors and nurses stage a protest against the rape and murder of a woman doctor inside the RG Kar Medical College and Hospital in Calcutta on Sunday, Aug. 11, 2024. PTI Photo