“Tell me, did Rabindranath use ‘Sri’ before his name or not?” asks Paritosh Bhattacharya with a twinkle in his eye as he digs into his cloth bag and brings out about a dozen books one by one.

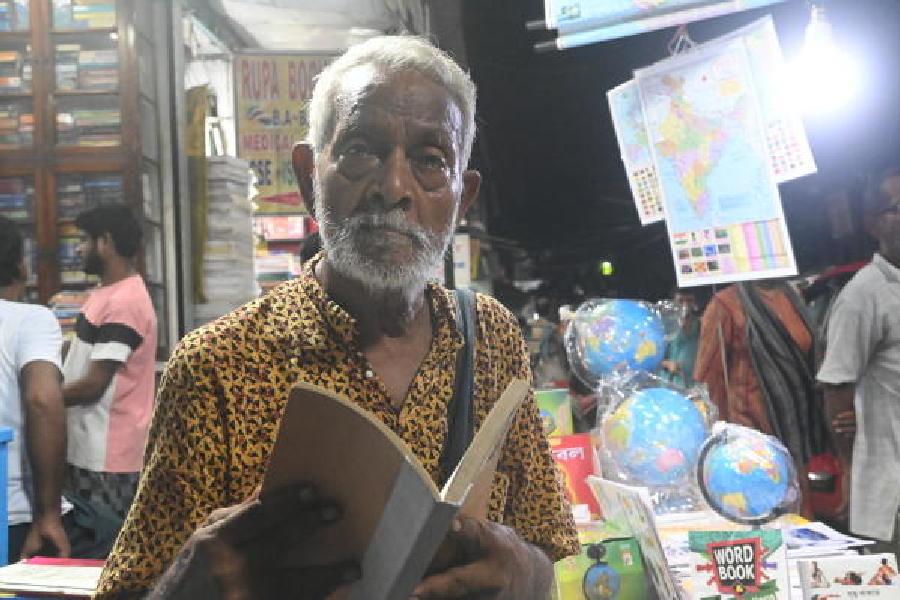

Every evening, Bhattacharya, 81, comes to Coffee House on College Street with a small collection of books and moves from table to table, stopping at the one that shows some interest. The books are striking; usually old and mostly Bengali. He sells them, at very affordable prices.

He is certain to offer books that you want to pick up despite the heap lying unread at home — a first edition of Nazrul or a Signet edition of Banalata Sen, with the cover illustration by Satyajit Ray, or an early edition of a volume of poetry by Rabindranath Tagore.

A resident of Madhyamgram, he comes to College Street every day by first taking the bus to Madhyamgram station, then the train to Sealdah and then walking to College Street. He goes back home the same way, sometimes quite late.

A thin, short man, with white hair and beard, wearing an unironed cotton kurta, he first looks at you piercingly as you go through his books. He is trying to gauge what category of reader you are. He is exceptionally well-read.

“So you don’t know. Rabindranath did use ‘Sri’ before his name till some time,” he says and shows a 1921 edition of Balaka, a book of poems by Rabindranath. Having put me in my place and at the same time laughing about it — “I have to do some ‘bahaduri’ (showing off) in my trade” — he begins to talk. That is what he likes to do.

His real work is to find out readers. And reading, he says, keeps him alive.

His childhood was very hard. It did not allow him to go to school or finish college.

He had come to Calcutta with his mother and elder sister from Chittagong, after Partition, as refugees. He was very young then. His father had died before his birth. They lived for a while in a north Calcutta slum, which he hated. His mother died after a few years and this unsettled him even more. He moved from address to address, but somehow kept reading whatever he could lay his hands on.

“I was often reading books that I didn’t understand,” says Bhattacharya.

To survive, from a very early age he began to sell the one thing he knew well: books. He would buy the books from old newspaper vendors, who bought old books too by weight. Bhattacharya, too, bought them by weight.

The old newspaper stores proved a treasure trove. In the pile he bought, he located gems. He got hold of a first edition of Michael Madhusudan Dutta’s Meghnadbadh Kavya and Raga-Kalpadruma by Krishnananda Vyasadeva, written in Devanagari script, from the books from newspaper stores.

“The contents of Raga-Kalpadruma are evidence that the portrayal of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb as unmitigatedly intolerant towards Hinduism is simplistic,” says Bhattacharya.

He has found family histories, such as the history of a branch of the Kar family settled in Calcutta. He has in his collection rare local histories, including a history of Barasat.

He had come across a magnificent collection of old books in the possession of a descendant of Rani Rasmoni. “So many books… where do I begin?” he asks.

In the same breath, he introduces me to his friend Amitava Kar, a writer.

Everything buzzes around Bhattacharya above the Coffee House din. He says that from the late 1950s, when he first started visiting Coffee House, he was introduced to M.N. Roy’s ideas and the Radical Humanists. “They had a little place above Coffee House, which still exists,” he says.

It is time for Coffee House to close for the day. “I can’t talk about my life in half an hour,” he says. “If you want to talk to me, come to my house in Madhyamgram,” he adds and invites me warmly.

As a parting shot, he recites a few lines of a beautiful lyrical poem, pronouncing the words perfectly. “Who wrote this?” he demands. I guess it is not Rabindranath, though the lyricism and cadence remind of him. “This is Jyotirindranath,” he smiles. Jyotirindranath is one of Rabindranath’s elder brothers. Rabindranath’s brilliance, many feel, may have obscured that of the other Tagores.

I reach Bhattacharya’s house in interior Madhyamgram on a sweltering hot afternoon. He lives in two small rooms on the ground floor of a building.

He had shifted here from north Calcutta, where he had settled down after marrying the woman he loved. They had a son, who lives in Durgapur. Bhattacharya’s wife died in 2021.

“Many people I meet at Coffee House come here with me,” says Bhattacharya. He has numerous admirers and has had as friends remarkable persons, including famous writers. He is a celebrity in the College Street area.

Not that it has made a difference to his material circumstances. But he does not seem to care.

His living space is a storehouse of books. They are everywhere, on tables, beds, chairs, floors, verandah. Everything else seems subsidiary, if not neglected — including cooking, tidying, even perhaps eating and sleeping.

“Achcha abhabe swabhab jaye, na swabhabe abhab?” Bhattacharya asks me abruptly. (Is it want that creates habits or habits that create want?) I am not wise enough to attempt an answer.

Every book at his place tells a story. Bhattacharya loves to talk about not only what is between the covers, but the histories of the books, where they were, how they arrived. Now he gets his books also from sources other than old newspaper vendors.

He talks about how he went to the Himalayas with his wife and son, when his son was small. Bhattacharya, in his enthusiasm, could hardly wait to reach Gomukh, but his wife felt afraid and stopped on the way. Reaching the height and then looking below, though, was life-changing, sublime.

He quotes a passage from Kalidasa’s Kumarsambhavam. His pronunciation is chaste and the effect of the rendition of the longish passage is quite stunning on me. “Yes, I learnt a bit of Sanskrit. And you have to learn some passages by heart. I have to do some bahaduri,” he laughs again.

He also informs that he is writing an autobiography.